Could solar power stations floating in space be the answer to our energy needs?

Giant power-generating panels could face the sun 24 hours a day, write Amanda Jane Hughes and Stefania Soldini

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

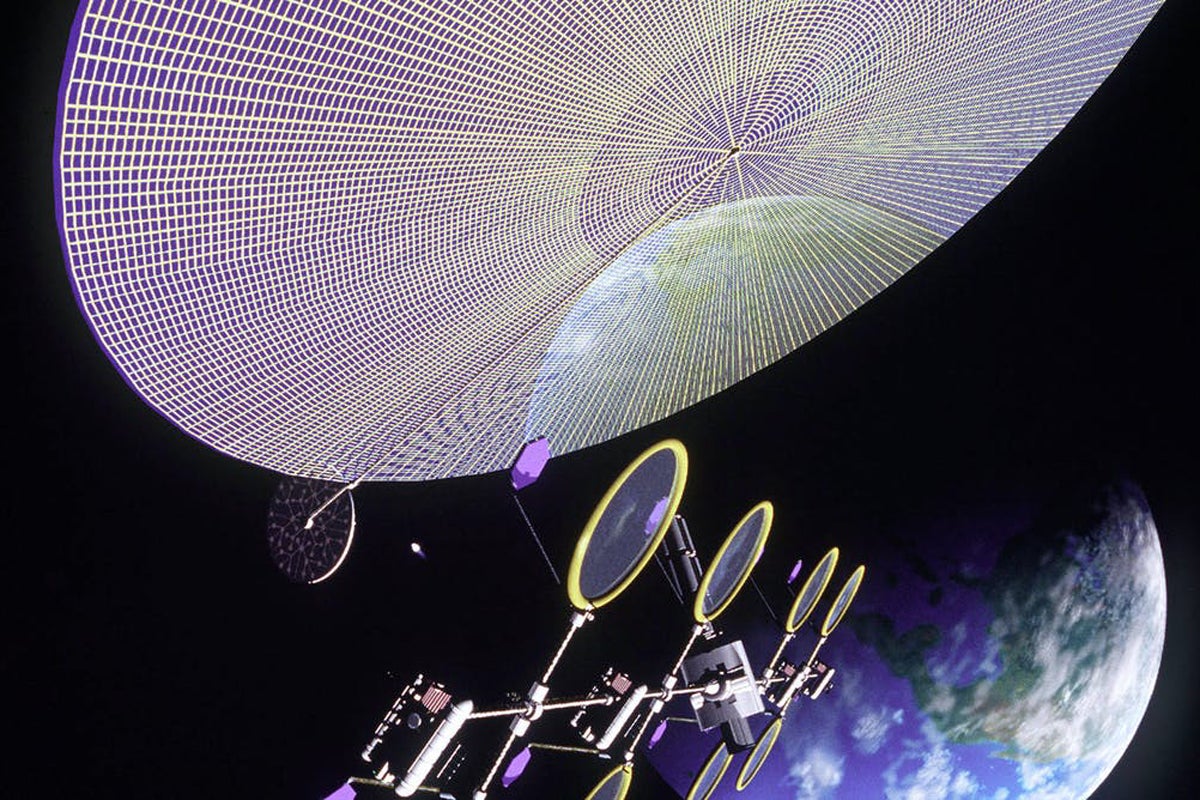

Your support makes all the difference.It sounds like science fiction: giant solar power stations floating in space that beam down enormous amounts of energy to Earth. And for a long time, the concept – first developed by Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in the 1920s – was mainly an inspiration for writers.

A century later, however, scientists are making huge strides in turning the concept into reality. The European Space Agency has realised the potential of the idea and is looking to fund such projects, predicting that the first industrial resource we will get from space is “beamed power”.

Climate change is the greatest challenge of our time, and will require radical changes to how we generate and consume energy.

Renewable energy technologies have developed drastically in recent years, with improved efficiency and lower cost. But a major barrier to their uptake is that they don’t provide a constant supply of energy. Wind and solar farms produce energy only when the wind is blowing or the sun is shining – but we need electricity around the clock, every day. Ultimately, we need a way to store energy on a large scale before we can make the switch to renewable sources.

A possible way around this would be to generate solar energy in space. There are many advantages to this. A space-based solar power station could orbit to face the sun 24 hours a day. The Earth’s atmosphere also absorbs and reflects some of the sun’s light, but solar cells above the atmosphere will receive more sunlight and produce more energy.

But one of the key challenges to overcome is how to assemble, launch and deploy such large structures. A single solar power station may have to be as much as 10 km squared in area – equivalent to 1,400 football pitches. Using lightweight materials will also be critical, as the biggest expense will be the cost of launching the station into space on a rocket.

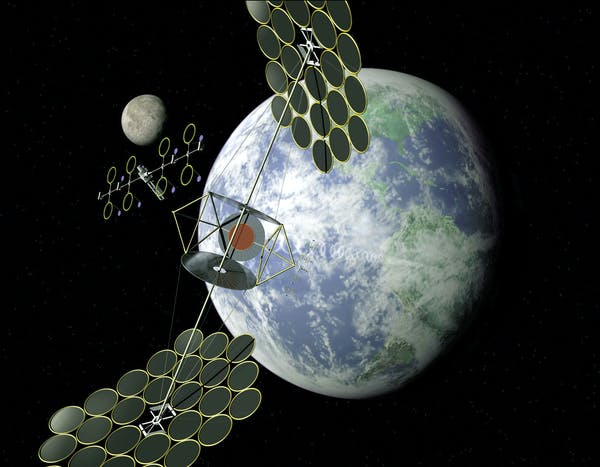

One proposed solution is to develop a swarm of thousands of smaller satellites that will come together to configure a single, large solar generator. In 2017, researchers at the California Institute of Technology outlined designs for a modular power station, consisting of thousands of ultralight solar cell tiles. They also demonstrated a prototype tile weighing just 280g per sq m, similar to the weight of card.

There is still a lot of work to be done in this field, but the aim is that solar power stations in space will become a reality in the coming decades

Recently, developments in manufacturing, such as 3D printing, are also being looked at for this application. At the University of Liverpool, we are exploring new manufacturing techniques for printing ultralight solar cells on to solar sails. A solar sail is a foldable, lightweight and highly reflective membrane capable of harnessing the effect of the sun’s radiation pressure to propel a spacecraft forward without fuel. We are exploring how to embed solar cells on solar sail structures to create large, fuel-free solar power stations.

These methods would enable us to construct the power stations in space. Indeed, it could one day be possible to manufacture and deploy units in space from the International Space Station or the future lunar gateway station that will orbit the moon. Such devices could in fact help provide power on the moon.

The possibilities don’t end there. While we are currently reliant on materials from Earth to build power stations, scientists are also considering using resources from space for manufacturing, such as materials found on the moon.

Another major challenge will be getting the power transmitted back to Earth. The plan is to convert electricity from the solar cells into energy waves and use electromagnetic fields to transfer them down to an antenna on the Earth’s surface. The antenna would then convert the waves back into electricity. Researchers led by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency have already developed designs and demonstrated an orbiter system that should be able to do this.

There is still a lot of work to be done in this field, but the aim is that solar power stations in space will become a reality in the coming decades. Researchers in China have designed a system called Omega, which they aim to have operational by 2050. This system should be capable of supplying 2GW of power into Earth’s grid at peak performance, which is a huge amount. To produce that much power with solar panels on Earth, you would need more than six million of them.

Smaller solar power satellites, like those designed to power lunar rovers, could be operational even sooner.

Across the globe, the scientific community is committing time and effort to the development of solar power stations in space. Our hope is that they could one day be a vital tool in our fight against climate change.

Amanda Jane Hughes is a lecturer in the Department of Mechanical, Materials and Aerospace Engineering, at the University of Liverpool. Stefania Soldini is a lecturer in aerospace engineering at the University of Liverpool. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments