Skin cells shine a light on sleep's 'larks' and 'owls'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

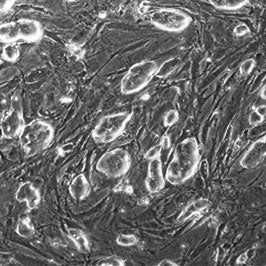

Your support makes all the difference.Microscopic fragments of skin can be used to tell whether someone is an early-rising "lark" who springs to life at sunrise, or a natural "owl" who struggles to get out of bed in the morning but still feels awake late at night.

Skin cells carry an in-built timing mechanism set by the central biological clock of the body which determines whether someone is an owl or a lark, according to a study that holds out the promise of developing new treatments for sleeping disorders.

The study found that people's preferences for rising early or late are encoded in their genes - and the molecules of their skin cells - although the scientists emphasised that other factors also play a role in influencing the time that someone likes to rise in the morning.

Studies of identical and non-identical twins have shown that genes play a part in whether someone is by nature a lark or an owl but the latest research is probably the first to show that human skin cells on their own can be used to test for someone's sleeping preferences.

The findings are part of the wider effort of research into how the human body deals with the shifts in patterns of activity which are needed to cope with the 24-hour cycle of day and night. Eventually scientists hope to use the results to treat people with sleeping disorders, such as those resulting from seasonal-affected disorder.

A research team led by Steven Brown of the University of Zurich analysed the sleeping behaviour of 28 people and found that they could divide the experiment's volunteers into 11 "larks" and 17 "owls" based on a questionnaire of their normal daily routines.

After taking skin samples from the volunteers, the scientists inserted into each cell a gene that lights up in ultraviolet light when the cell is metabolically most active. The gene allowed the scientists to follow the circadian rhythm of the cells as they waxed and waned over a 24-hour period.

When the cells and the gene were at their highest activity, the intensity of the light increased. This phenomenon allowed the scientists to measure the length of activity showed by each cell and compare this to the natural sleeping tendencies of the volunteer in question.

The study, which is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that the skin cells from the extreme early risers has the shortest luminescence period, whereas those from the very-late risers had the longest period. This suggested that the extreme early risers had a short daily cycle and long nightly cycle, which was reversed in the late risers.

The scientists believe that a person's preferences for early or late phases of daily activity might be determined by the length of the "circadian" period, the period of roughly 24 hours that controls the biological clock of the body.

A part of the brain called the suprachiasmic nucleus acts at the body's pacemaker by analysing light levels reaching the eye and sending messages to the pineal gland at the base of the brain, which produces the sleep hormone melatonin.

The scientists believe that extreme early risers have a shorter circadian oscillation than the extreme late risers, but they also found other differences between the two groups.

"We find not only period length differences between the two classes, but also significant changes in the amplitude and phase-shifting properties of the circadian oscillator among individuals with identical 'normal' period lengths," the scientists said.

"Our observations in fibroblasts [skin cells] suggest a strong genetic contribution of an endogenous circadian clock to human daily behaviour, and show that the specific properties of this clock can be measured in peripheral cells at a molecular level."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments