Sir John Cornforth: Who was the pioneering chemist who overcame deafness to win a Nobel Prize?

Today's Google Doodle celebrates a revered molecular scientist who broke new ground

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

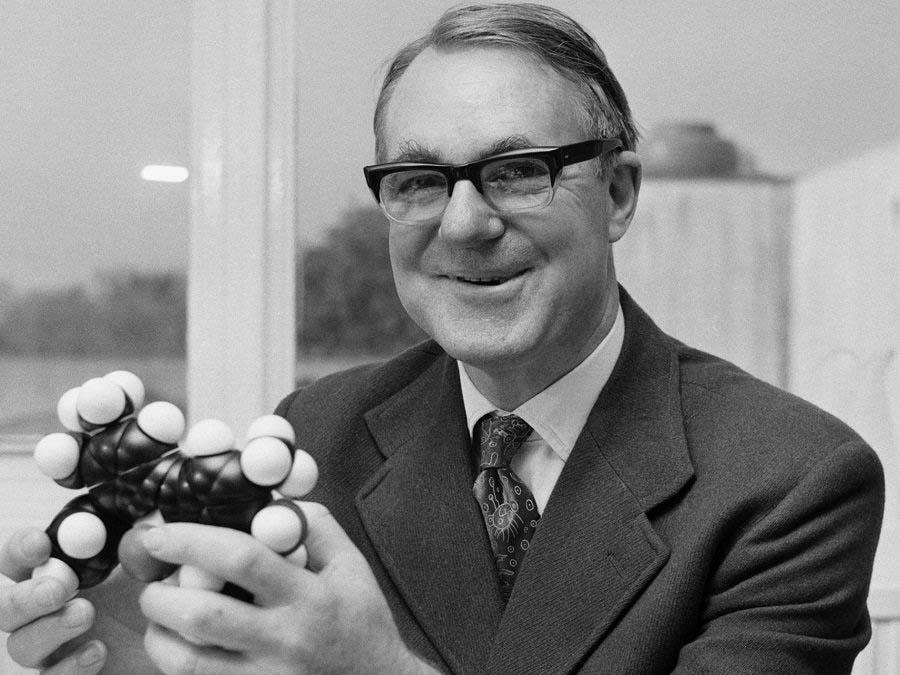

Your support makes all the difference.Google’s new Doodle marks the centenary of Australian scientist Sir John Warcup Cornforth (1917-2013), winner of the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1975.

Cornforth was awarded the honour with colleague Vladimir Prelog for their work on the stereochemistry of enzyme-catalysed reactions, which is to say the spatial arrangement of atoms and how their structure affects organic compounds.

If that sounds complicated, even the man himself had difficulty describing his field succinctly. “This subject is difficult to explain to the layman," he admitted.

Here are five things you might not know about a much-admired scientific mind.

1. John went deaf aged just 16

Cornforth was born in Sydney on 7 September 1913, the son of John Warcup Cornforth Sr, an English schoolmaster, and Hilda Eipper, an Australian maternity nurse descended from Presbyterian missionaries.

An avid student at Sydney Boys’ School, John suffered from otosclerosis from the age of 10, a condition causing a deterioration in his hearing that ended in total deafness by the time he turned 16.

Attending the University of Sydney while still in his teens, Cornforth’s disability led him to favour laboratory work over lectures and therein set him on the path to studying chemistry.

2. He met the love of his life over a broken beaker

Busy working in the lab as a second year, Cornforth was approached for help one day by fellow student Rita Harredence, who had cracked a Claisen flask by accident. An accomplished glassblower, John was able to repair the receptacle using a blowpipe. Their eyes met as he returned it to her and, by all accounts, sparks flew.

The pair were inseparable from that moment on and married in 1941, having three children together: John, Brenda and Philippa.

Rita, a distinguished biochemist herself, lived to the grand old age of 97, passing away in November 2012.

Accepting his Nobel Prize, John paid moving tribute to Rita:

“Throughout my scientific career my wife has been my most constant collaborator. Her experimental skill made major contributions to the work; she has eased for me beyond measure the difficulties of communication that accompany deafness; her encouragement and fortitude have been my strongest support.”

3. Cornforth was instrumental in developing penicillin during the Second World War

Having graduated from Sydney in 1937 with a first and a medal for academic excellence, Cornforth moved with Rita to England where both had been awarded postgraduate research scholarships to study at Oxford.

Cornforth’s work there during the Second World War involved the purification and concentration of penicillin for use in the treatment of wounded soldiers by the British Army.

Cornforth’s experimentation built on the work of Howard Florey and sought the optimal conditions for the drug’s production. He contributed to The Chemistry of Penicillin, an influential study of the antibiotic.

4. Cornforth’s work in stereochemistry was carried out in Kent

His greatest contribution to his field was carried out at Shell’s Milstead Laboratory of Chemical Enzymology at Sittingbourne, Kent, where Cornforth served as co-director (1962-68) and then director (1968-75). There he investigated enzymes that spark change in compounds by taking the place of hydrogen atoms in a substrate’s molecular chains and rings.

Using hydrogen isotopes, he identified which string of a substrate’s atoms can be replaced by an enzyme to change its nature. This enabled Cornforth to explain the biosynthesis of complex molecules like cholesterol, allowing fellow organic chemists to follow in his stead, a contribution for which he was duly celebrated.

5. The Nobel Prize was just one of many accolades he accumulated

Cornforth would go on to work as a professor at the universities of Warwick and Sussex and at the University of California in Los Angeles over the course of his long career.

He was awarded a CBE for his services to organic chemistry in 1972, knighted in 1977 and made a Companion of the Order of Australia in 1991. He was also elected to the Royal Society in 1953 and won the institution’s prestigious Davey Medal in 1968.

Cornforth died an atheist in Sussex on 8 December 2013, little more than a year after Rita’s passing, a final testament to their enduring love.