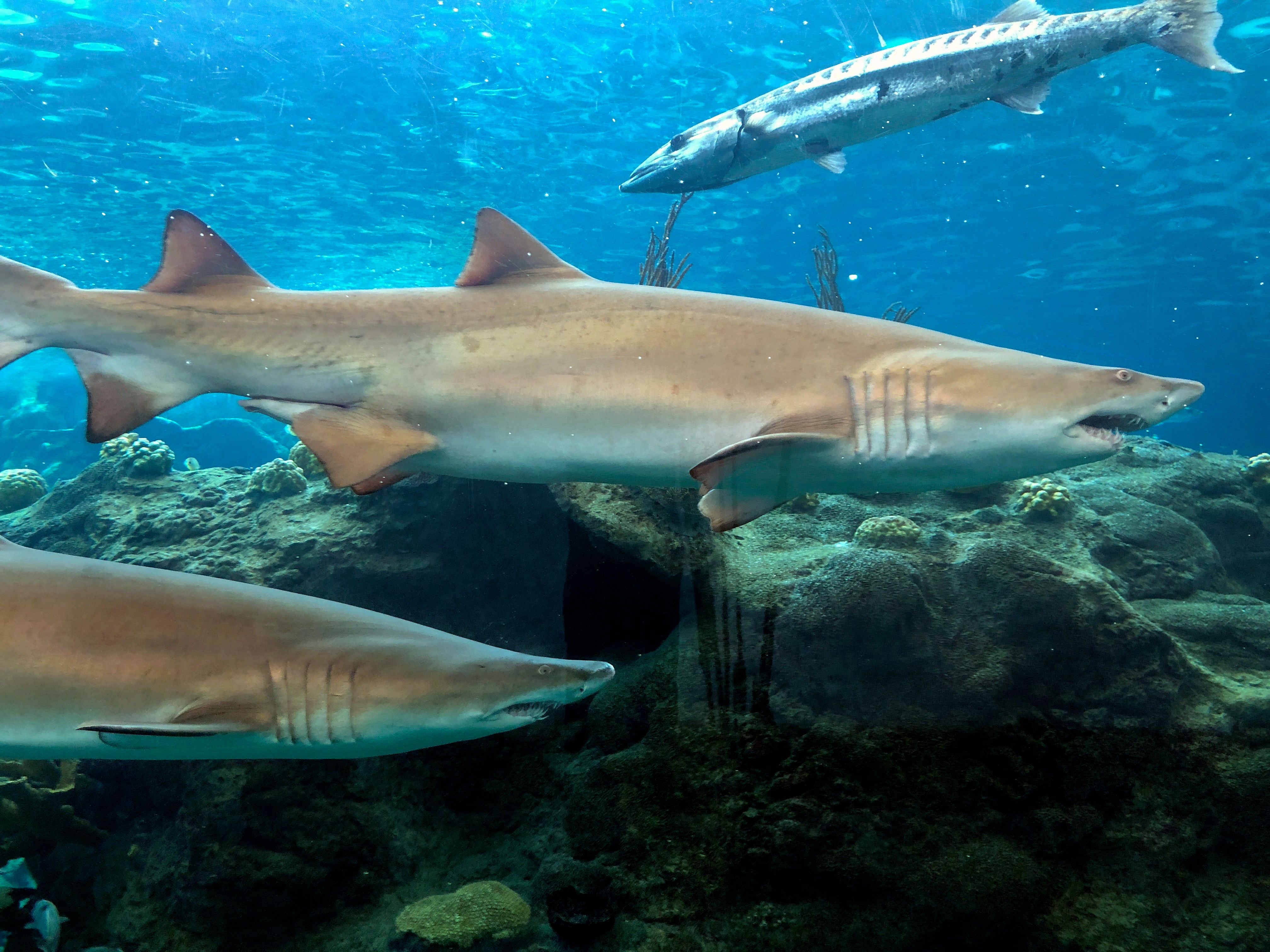

Mysterious event wiped out 70 per cent of world’s sharks 19 million years ago

Study helps understand context of shark population changes over the last 40 million years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have discovered a massive die-off of sharks about 19 million years ago – twice the number of deaths that occurred during a much earlier mass extinction event that wiped out three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth.

The researchers, including those from the Yale University in the US, said 70 per cent of the world’s sharks died off 19 million years ago with an even higher toll for those in the open ocean, rather than coastal waters.

According to the study published in the journal Science, the oceans during this period were home to more than 10 times the numbers seen today.

“We happened upon this extinction almost by accident,” Elizabeth Sibert, study co-author from Yale’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, said in a statement.

“I study microfossil fish teeth and shark scales in deep-sea sediments, and we decided to generate an 85-million-year-long record of fish and shark abundance, just to get a sense of what the normal variability of that population looked like in the long term,” Ms Sibert said.

The scientists found a sudden drop off in shark abundance around 19 million years ago that was twice the levels experienced during the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction event 66 million years ago.

However, they said the study could not ascertain the reason behind the die off.

“This interval isn’t known for any major changes in Earth’s history, yet it completely transformed the nature of what it means to be a predator living in the open ocean,” Ms Sibert said.

According to the researchers, the study helps understand the context of shark population changes over the last 40 million years.

They believe the findings can shed light on what repercussions may follow dramatic declines in sharks in modern times.

Further research could confirm if the shark die-off caused remaining populations to change their habitat preferences to avoid the open ocean, and may also explain why their numbers did not rebound after the die-off, the scientists said.

“This work could tip-off a race to understand this time period and its implications for not only the rise of modern ecosystems, but the causes of major collapses in shark diversity,” Pincelli Hull, an assistant professor of Earth and planetary science at Yale – who was not part of the study – said in a statement.

“It represents a major change in ocean ecosystems at a time that was previously thought to be unremarkable,” Ms Hull added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments