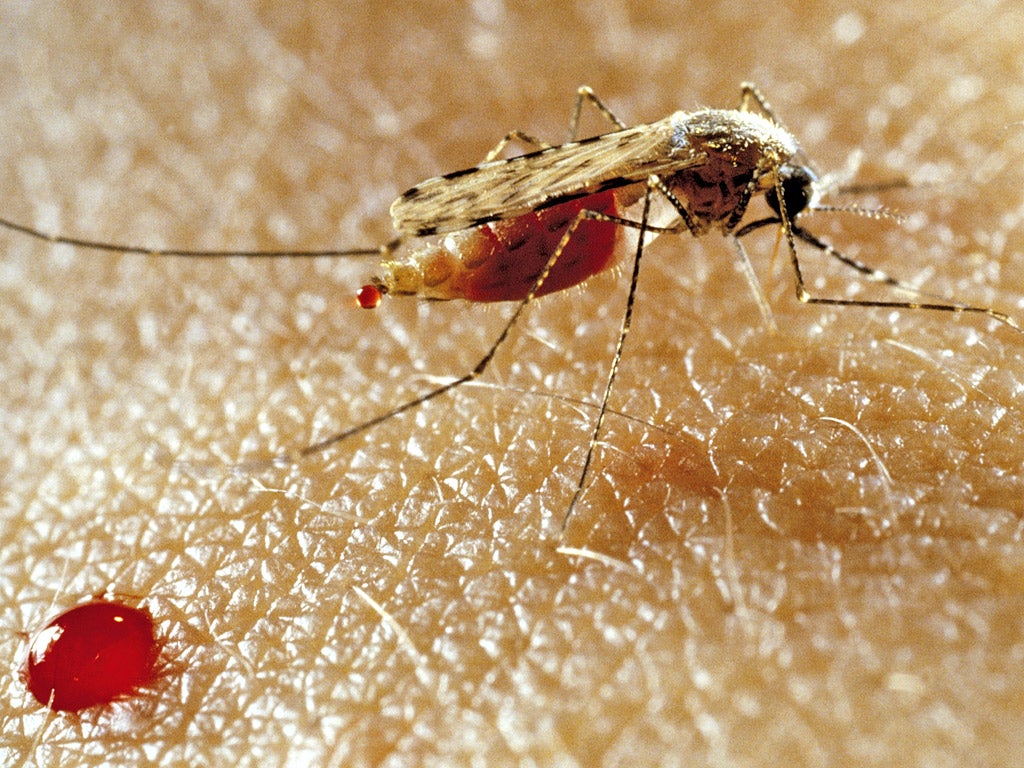

Secrets of insect repellent DEET could prove decisive in the war on malaria, dengue and West Nile fever

Researchers use new screening method to find four repellents that are as powerful as substance used effectively for more than 60 years to protect people

Scientists have uncovered the secrets behind the world’s most common insect repellent – helping them find new ways to protect people from diseases such as malaria, dengue and West Nile fever.

The researchers have used a new screening method to find four insect repellents that are as powerful as DEET, a substance that has been used effectively for more than 60 years to protect people against mosquitoes and other biting insects.

Three have already been deemed safe for human use, and are even found in certain kinds of food. The fourth is a chemical found in the pheromone trails used by ants to find their way home.

Although DEET – diethyl-meta-toluamide – is a highly effective mosquito repellent, it can dissolve man-made fibres and plastics. It is also expensive and inconvenient for use in many parts of Africa, where the need for repellent is greatest.

One of the problems in finding alternatives to DEET is that, until now, scientists have not been sure how the substance works. The study, published in Nature, has however found that DEET triggers a certain kind of nerve receptor called Ir40a, found in the olfactory antenna of insects, which causes them to flee from the chemical’s odour.

Although the work was carried out on fruit flies, the researchers said that the Ir40a receptor is found in the antennae of many other insect pests, such as mosquitoes, head lice and flour beetles. However, the same mechanism does not appear to act as an insect repellent on honey bees, which are commercially important for pollinating crops.

“Until now, no one had a clue about which olfactory receptor insects used to avoid DEET. Without the receptors, it is impossible to apply modern technology to design new repellents,” said Professor Anandasankar Ray, an entomologist at the University of California, Riverside, who led the study.

“Ir40a and its related proteins are conserved not only in flies and mosquitoes, but also in many other insects that are human and plant pests. Our findings could lead to a new generation of cheap, affordable repellents that could protect humans, animals and, in the future, our crops as well,” Professor Ray said.

“We could find truly novel repellents that have remarkable properties such as large-scale spatial protection and long-term protection.”

Once the researchers had been able to identify the critical role of the Ir40a protein in avoiding the odour of DEET, they were able to construct a genetically-engineered insect antenna that glowed fluorescent green in the presence of any airborne substance similar to DEET.

With this method they were able to screen some 500,000 substances for their insect-repellent properties, and found eight that were strong repellents on flies. Four of these proved highly effective against mosquitoes and three were already approved for human consumption, Professor Ray said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks