Scientists unearth evidence of centuries-old aftershocks

Some of the most violent earthquakes that have occurred unexpectedly in places with no recent record of tremors may be the aftershocks of previous earthquakes that took place decades or even centuries ago, scientists have discovered.

Earthquakes usually occur at the boundary of two or more tectonic plates – the massive chunks of the earth’s crust that grind slowly against one another. However, they can also occur many hundreds of miles from a fault line and it is these earthquakes that scientists believe may be the result of long aftershocks rather than background seismic activity.

A laboratory study that tested how tectonic faults work has found that the further away an earthquake is from such fault line, the stronger the likelihood that it could be the long aftershock of a previous earthquake that has taken many years to make itself felt in terms of a second series of violent ground movements.

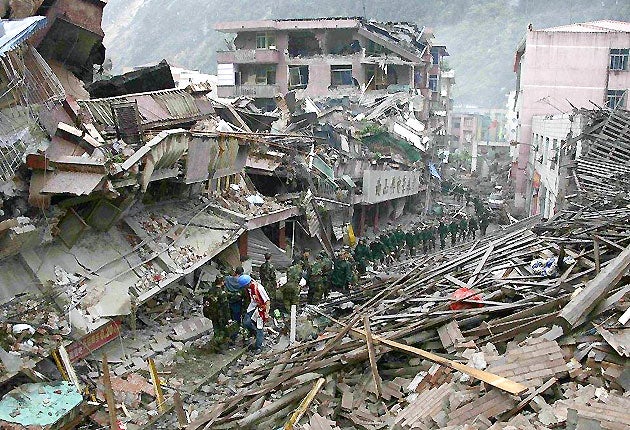

The finding could explain many unexpected earthquakes in the centre of continental shelves, such as the disastrous quake in Sichuan in the heart of China in May 2008 which killed at least 68,000 people and injured up to 400,000 more. At 7.9 on the earthquake scale it was one of the most deadly quakes in history.

Mian Liu, professor of geological sciences at the University of Missouri in Columbia, said that scientists have tried to predict the occurrence of larger earthquakes by looking at the frequency of smaller ones, which is why the Sichuan earthquake took seismologists by surprise.

“Until now, we’ve mostly tried to tell where large earthquakes will happen by looking at where small ones do,” Professor Liu said. But in Sichuan there had not been many earthquakes in the past few hundred years, he added.

The study, reported in the journal Nature, found that aftershocks near to tectonic boundaries continue for only a few years but further away they can occur over a timescale of decades and centuries. Recent earthquakes in Canada’s Saint Lawrence valley, for instance, may be the aftershocks of an earthquake that occurred in 1663.

Similarly, a magnitude 7 earthquake that occurred near a town called New Madrid in Mississippi in 1811 is still causing aftershocks that can be felt in the American mid-west because these shocks are the result of movements that are 100 times slower than the movements that occur near to a tectonic fault line.

“A number of us had suspected this because many of the earthquakes we see today in the Midwest have patterns that look like aftershocks. They happen on the faults we think caused the big earthquakes in 1811 and 1812, and they’ve been getting smaller with time,” Professor Liu said.

“Aftershocks happen after a big earthquake because the movement on the fault changed the forces in the earth that act on the fault itself and nearby. Aftershocks go on until the fault recovers, which takes much longer in the middle of a continent,” he said.

The aim of the research is that it may help to make better predictions about when and where an earthquake is likely to happen, said Professor Seth Stein at Northwestern University.

“Instead of just focusing on where small earthquakes happen, we need to use methods like GPS satellites and computer modelling to look for places where the earth is storing up energy for a large future earthquake. We don’t see that in the Midwest today, but we want to keep looking,” Professor Stein said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks