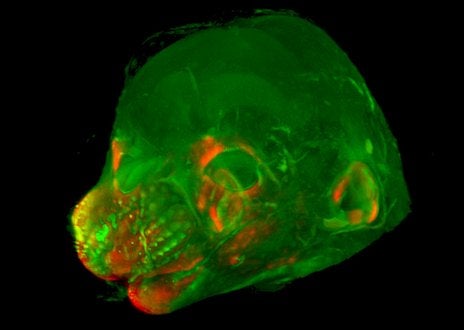

Scientists identify genetic 'enhancers' that control facial development in mice

Research might one day help us mitigate facial defects in humans

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Research studying facial development in mice has given scientists new insights into the genetic controllers that determine the appearance of human faces.

An international team of scientist identified more than 4,000 small regions in the DNA that appear to influence facial features, noting that even small changes to these so-called ‘enhancers’ had “subtle but significant effects” on the shape of the face and the skull.

Although the research was carried out on mice, the scientists involved believe that many of their findings will also be applicable to humans.

"We're trying to find out how these instructions for building the human face are embedded in human DNA,” said Professor Axel Visel of the Joint Genome Institute at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, to the BBC.

"Somewhere in there there must be that blueprint that defines what our face looks like."

The ‘enhancers’ in question are short strings of DNA that function as switches for genes. The team of scientists experimented by turning three of these genes on and off in mice embryo, and then studying how the animals developed.

"In the mouse embryos we can see where exactly, as the face develops, this switch turns on the gene that it controls,” said Professor Visel.

However, once the mice had matured the scientists found it difficult to detect the slight differences in the facial and cranial structure – although these might have been readily apparent to other mice.

They worked around this by taking CT scans of the mice and comparing them with none genetically-altered specimens. The changes were subtle, but showed a range of changes in the skull in both width and length.

"What this really tells us is that this particular switch also plays a role in development of the skull and can affect what exactly the skull looks like," said Professor VIsel.

It’s hoped that the research will help understanding of how and why facial defects such as cleft palates develop in the womb, perhaps allowing scientists in the future to identify and even mitigate these conditions.

However, Professor Visel also stressed that these developments would not lead to the custom designing of human faces in the near future, and that the genetic processes that determine facial appearances are many times more complex than the crude ‘on/off’ switches of these genetic ‘enhancers’.

'Fine Tuning of Craniofacial Morphology by Distant-Acting Enhancers' is published in Science

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments