Scientists identify brain region that helps people control word pronunciation

This brain region could be impaired in people with neurological disorders, study hints

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have identified a region of the brain that is responsible for making sure people say words as intended, an advance could lead to the development of new therapies to treat speech problems.

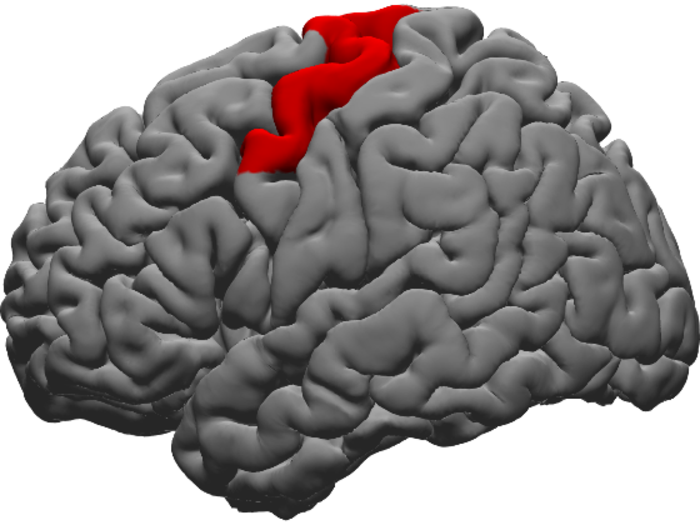

This region called the dorsal precentral gyrus – crossing the folded surface of the top of the brain – plays a major role in helping people use the sound of their voices to control their word pronunciation, the study, published last week in the journal PLoS Biology, noted.

In the new research, scientists led by a team from New York University Grossman School of Medicine analysed half-dozen subregions of the brain’s surface layer – or cerebral cortex – that are known to control how people move their mouth, lips, and tongue to form words.

These regions, the researchers say, are also known to help people process what they hear themselves saying.

This process by which the brain assess feedback signals from the body as people speak – known as the auditory feedback control of speech – is impaired in various neurological disorders ranging from stuttering to aphasia, the study noted.

However, they say, the precise role of each of the brain subregions involved in this process in real-time has remained unclear due to technical difficulties in assessing the brain directly while people are alive and talking.

The new study assessed the brain’s feedback mechanisms for controlling speech, particularly whether the dorsal precentral gyrus is responsible for generating the brain’s initial memory for how spoken words are “supposed” to sound.

It also assessed whether this brain region played a role in noticing errors in how words were actually spoken.

It found that while three cortical regions were primarily involved in correcting errors in speech, only the dorsal precentral gyrus, dominated when delays in speech – meant to signify feedback errors – were maximised.

These brief feedback delays ranged from 0 milliseconds to over 200 milliseconds and were designed to mimic real-life slurring of speech, the researchers explained.

“Our study confirms for the first time the critical role of the dorsal precentral gyrus in maintaining control over speech as we are talking and to ensure that we are pronouncing our words as we want to,” study senior author and neuroscientist Adeen Flinker, said in a statement.

“Now that we believe we know the precise role of the dorsal precentral gyrus in controlling for errors in speech, it may be possible to focus treatments on this region of the brain for such conditions as stuttering and Parkinson’s disease, which both involve problems with delayed speech processing in the brain,” Dr Flinker said.

In the research, the scientists analysed thousands of recordings from over 200 electrodes placed in each of the brains of 15 people with epilepsy, who were already scheduled to undergo surgery to pinpoint the source of their seizures.

The patients, mostly men and women in their 30s and 40s, were recorded in 2020 at NYU Langone, the study noted.

The participants performed standardised reading tests during a planned break in their surgery, saying aloud words and short statements, while wearing headphones so that their words could be recorded and played back to them as they spoke.

Researchers then recorded electrical activity inside most subregions of the patients’ brains as they heard themselves talking, and repeated the process while delaying the feedback by milliseconds.

The scientists say by introducing errors in normal speech, they could compare and contrast the electrical signals to determine how various parts of the brain function and control speech.

“These results suggest that dorsal precentral gyrus plays an essential role in processing auditory error signals during speech production to maintain fluency,” the researchers concluded in the study.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments