Science news in brief: uncovering the secrets to (nearly) eternal life with the 2,000-year-old fungus

And a roundup of other stories from around the world

Giant fungus is older, bigger and rarely mutates

Scientists first reported finding it in 1992: a giant mushroom that weighed as much as a blue whale and sprawled across more than 30 acres of forest in Michigan’s upper peninsula. It wasn’t some Alice-in-Wonderland-type toadstool but a 1,500-year-old parasitic mould, with growing tentacles that foraged beneath the soil for roots and decaying wood to devour.

Nearly 30 years later, the same scientists – using new technology for genetic analysis – wanted to know whether they had properly measured this unusual example of fungal life.

“We made this outlandish prediction that the fungus is more than 1,000 years old,” says James Anderson, now a retired mycologist and emeritus professor at the University of Toronto. “And so an obvious outcome of that, is after three decades, it ought still be there, and if not, we’d have some explaining to do.”

Recently they published what they uncovered in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. Their original humongous fungus, Armillaria gallica, is even older and bigger than first estimated: the 2,500-year-old parasite spreads across 180 acres of forest. And its genome harbors a mysterious survival strategy: an extremely low mutation rate.

This old beast harbored only about 160 mutations, orders of magnitude lower than expected.

More than two millenniums was plenty of time for cells to divide, copy and paste their DNA and send it – mistakes and all – from one generation to the next. But to get so few mutations, the fungus must have had very few cell divisions, which is crazy for a giant fungus made of microscopic cells. The researchers couldn’t measure how many cell divisions separate the bits of fungus spanning the length of nine football fields side by side, and so they couldn’t measure the mutation rate directly. It should have been huge, but it wasn’t.

“I think it’s a really interesting result with cutting-edge technology, and it opens up new questions about how organisms can remain stable over that length of time,” says Tom Bruns, a fungal ecologist at the University of California, Berkeley who reviewed the study.

Alarm in California as monarch butterfly population plummets

They arrive in California each winter, an undulating ribbon of orange and black. There, migrating western monarch butterflies nestle among the state’s coastal forests, traveling from as far away as Idaho and Utah only to return home in the spring.

This year, though, the monarchs’ flight seems more perilous than ever. The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, a nonprofit group that conducts a yearly census of the western monarch, says the population reached historic lows in 2018, an estimated 86 per cent decline from the previous year.

That in itself would be troubling news. But, combined with a 97 per cent decline in the total population since the 1980s, this year’s count is “potentially catastrophic”, according to biologist Emma Pelton.

“We think this is a huge wake-up call,” says Pelton, who oversees the survey and lives in Portland, Oregon.

The society has preliminary counts from 97 sites, most of them along California’s coast, representing an area that traditionally accounts for nearly 77 per cent of the state’s winter monarch population. In 2017, the sites hosted about 148,000 monarchs. But in 2018 that dropped to an estimated 20,456 monarchs, with large numbers of them counted in Pismo Beach, Big Sur and Pacific Grove.

Monarchs in the western part of the United States migrate for the winter to California, where they gather mostly among fragrant eucalyptus trees, which provide hospitable living conditions.

Monarchs from the eastern part of the United States, by contrast, winter in Mexico. Pelton says the count of eastern monarchs had not been released.

Pelton warns that if nothing is done to preserve the western monarchs and their habitat, the butterflies could face extinction. In a 2017 study, scientists estimated that the monarch butterfly population in western North America had a 72 per cent chance of becoming near-extinct in 20 years if the monarch population trend was not reversed.

Pelton says the trend could reverse if citizens and governments act now. Gardeners, for one, can plant milkweed to support the surviving monarchs. And towns could help local habitats thrive by planting new trees now so that in 20 years, generations of monarchs have new places to winter.

A woman’s work was sometimes blue

Anita Radini, an archaeologist at the University of York, spends a lot of time looking at tartar. Really old tartar.

Tartar, or dental plaque – that film of bacteria that feels like sweaters on your teeth – contains a wealth of information about what long-dead individuals encountered in their daily lives. Radini has seen all sorts of things trapped in it: food particles, textile fibres, DNA, pollen, bacteria and even wings of tiny insects.

But several years ago, when studying the dental plaque of a nun from medieval Germany, Radini saw something entirely new: particles of a brilliant blue. She showed the findings to Christina Warinner, another tartar expert, who was shocked.

“They looked like little robins’ eggs, they were so bright,” says Warinner, group leader of archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany. “I remember being dumbfounded.”

The scientists put together a multidisciplinary team of scholars and set out to unravel the origins of this blue dust. The results, described in a paper published recently in Science Advances, far exceeded the team’s expectations.

The particles, it turned out, were of ultramarine pigment, the finest and most expensive of blue colorings, made of lapis lazuli stone from Afghanistan. The German nun with the pigment in her teeth – B78, as she is known in the archaeological literature – was likely a painter and scribe of religious texts. And she must have been highly skilled to have been entrusted with such a rare powder, the researchers say.

The finding upends the conventional assumption that medieval European women were not much involved in producing religious texts. The skeleton of B78 dates to sometime between AD 997 and 1162. The nun was probably 45 to 60 years old when she died, and was buried in an unmarked grave near a women’s monastery in Dalheim, Germany.

The pigment likely ended up on the woman’s teeth as she used her mouth to shape her paintbrush. The researchers found ultramarine layered throughout B78’s dental plaque, which suggests she painted many books in her lifetime.

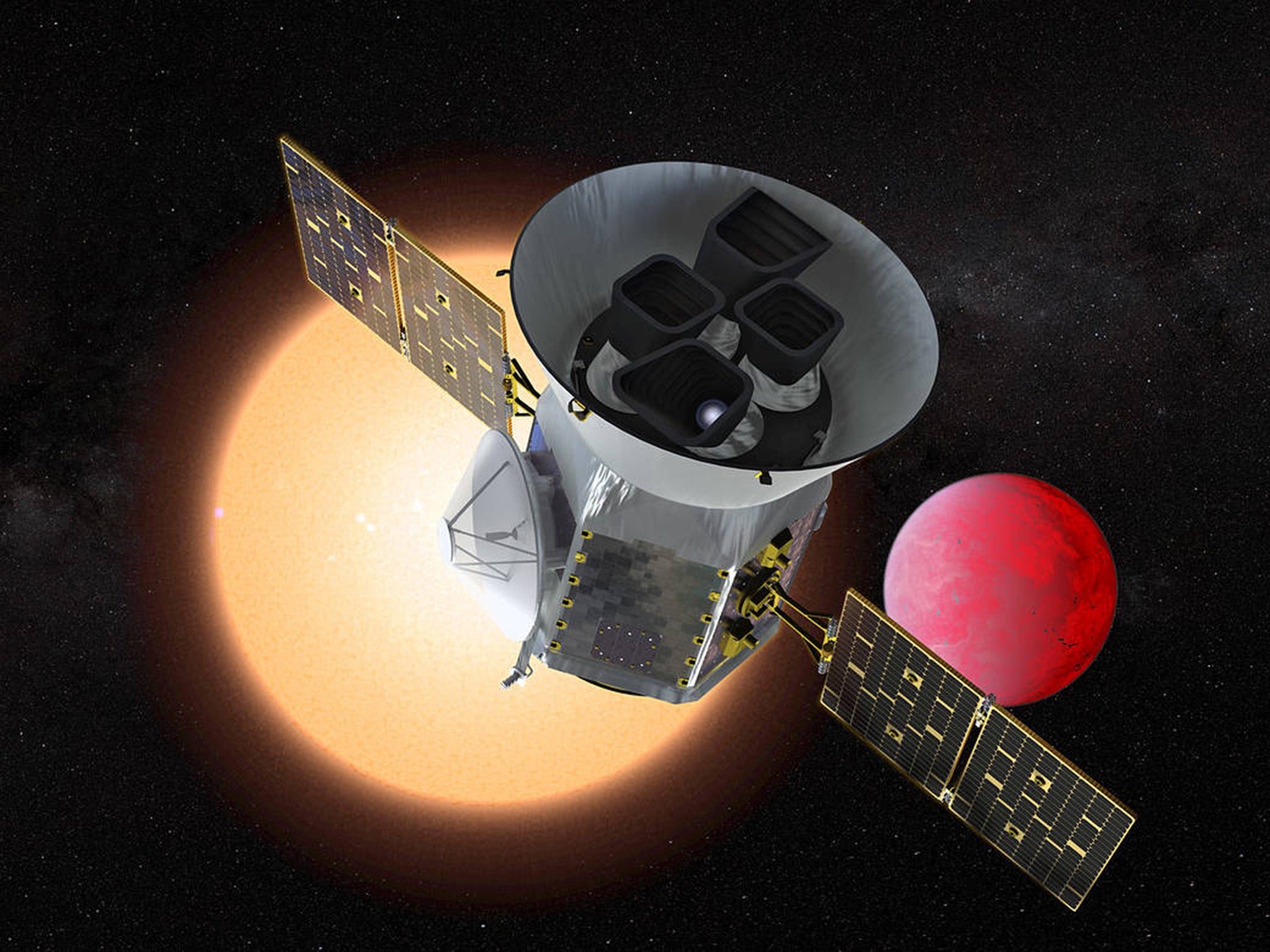

Another day, another exoplanet for Nasa’s Tess

Nasa’s new planet-hunting machine, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or Tess, is racking up scores of alien worlds.

Less than a quarter of the way through a two-year search for nearby Earthlike worlds, Tess has already discovered 203 possible planets, according to George R Ricker, an astrophysicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the leader of the project. Three of those candidates already have been confirmed as real planets by ground-based telescopes.

Last week, Ricker and his colleagues issued a progress report on humankind’s latest search for friends, or at least neighbours. The mission, they said at a meeting of the American Astronomical Association in Seattle, was well on track to its official goal of finding and measuring the masses of at least 50 planets that are no larger than four times the size of Earth.

“The torrent of data has already begun,” Ricker says.

All of these worlds would be located within 300 light years from here, our cosmic backyard, and close enough to be inspected by future telescopes, such as Nasa’s ever-upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, for signs of atmospheres, habitability and, perhaps, life.

The most recently confirmed of these planets received star billing in Seattle. In the words of its discoverer, Diana Dragomir of MIT, the planet is a “weird” ball or rock and some gas about three times the size of Earth. Every 36 days it orbits a dwarf star called HD 21749, about 53 light years away in the constellation Reticulum.

According to calculations by Dragomir, the planet is close enough to its star that its surface temperature is about 150C. That gives it one of the coolest surface temperatures found around such a star, but a bit toasty for life as we know it.

The planet’s nature is a puzzle. Its size puts it in a category called sub-Neptune, of which no examples exist in our own solar system. But it is much denser than Neptune (though not as dense as the Earth), Dragomir explained, suggesting that the new planet was mostly rock with a relatively small dense atmosphere.

Intriguingly, the team also detected hints of what might be a second planet circling the same star in a much closer orbit. It appears to be even smaller than Earth, which would make it the smallest planet Tess has yet found.

An elephant-size relative of mammals that grazed alongside dinosaurs

You can call it a Triassic titan. Or a pre-Jurassic juggernaut. Just don’t call it a dinosaur. Despite its appearance, this burly behemoth was a completely different prehistoric beast: a dicynodont.

Early relatives to present-day mammals, dicynodonts dominated Earth more than 200 million years ago, living first before, and then alongside, dinosaurs. Unlike dinosaurs, these herbivorous animals had short necks and large skulls. They were stocky like rhinos, toothless and had tusks and turtle-like beaks. Many ranged in sizes from pigs to hippos.

Now, scientists have uncovered a new species of dicynodont that towered over the rest, comparable in size to an elephant.

The newly discovered species, known as Lisowicia bojani, was 8.5 feet tall and about 15 feet long, and weighed 9 tonnes. It is both the largest and youngest dicynodont found so far and its discovery provides further evidence that these proto-mammals survived into the late Triassic period, past the point when many scientists had previously thought they went extinct.

The finding was published recently in the journal Science.

A team of paleontologists began uncovering the new dicynodont bones from a clay pit in the village of Lisowice in southern Poland in 2006.

“We found the first bones in 10 minutes,” says Grzegorz Niedźwiedzki, a paleontologist from Uppsala University in Sweden and an author on the study. “It was so clear to us that it’s a kind of El Dorado.”

During a dig, one of Niedźwiedzki’s colleagues unearthed a humerus that was found to belong to a dicynodont, not a dinosaur.

That was a surprise because the site had been dated to the late Triassic period and many paleontologists believed dicynodonts had died out by that time. The bones, the team says, provided further evidence that dicynodonts lived at least another 10 to 15 million years. That suggests that they did not go extinct before dinosaurs began conquering the land, but instead coexisted with them for some time.

But Niedźwiedzki says it wasn’t until 2011 when another colleague found a 3-foot-long scapula that the researchers began to comprehend the beast’s true size.

The team thinks the new dicynodont had a fully erect gait, like what you would see in a horse or elephant, as opposed to an intermediate crocodile-like or lizardlike sprawl.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks