Science news in brief: Clams using acid and magnetic moths on a mission

Plus a roundup of other stories from around the world

A clam that uses acid to make its home

When a scuba diver swims by a burrowing clam on one of the Pacific reefs, all they will see is what looks like a protruding pair of beautiful turquoise lips.

These are the clam’s feeding tissues, the rest of its body is safely encased in a cave of its own making.

How exactly a clam could do that has long been a mystery. But in a new study in Biology Letters, researchers revealed at long last a probable tool: the clam’s foot releases acid.

That’s illuminating because reefs are built by tiny coral organisms that create their own skeletons out of calcium carbonate.

Mix calcium carbonate and acid, however, and the molecules of the rock dissolve, in the same reaction you would see if you dropped an Alka-Seltzer into Coca-Cola, which is weakly acidic.

Extinct gibbon found in Chinese tomb

British researchers have identified a gibbon found in an ancient Chinese tomb as a never-before seen, now-extinct genus and species.

Samuel Turvey, a conservationist and gibbon expert, was touring a Chinese museum in 2009 when a partial skull caught his eye.

It had been found buried, along with in the tomb of Lady Xia, a grandmother of China’s first emperor Qin Shihuang, in what is now Shaanxi, China. The tomb was estimated to be 2,200-2,300 years old.

Turvey’s research team identified the animal as a member of a new genus and species, Junzi imperialis.

In comparison with living gibbons, the new one has a comparatively flat, small face, with canines that are particularly long for the animal’s size.

There are four gibbon genera alive in Asia today, including a species that is the most endangered mammal on earth.

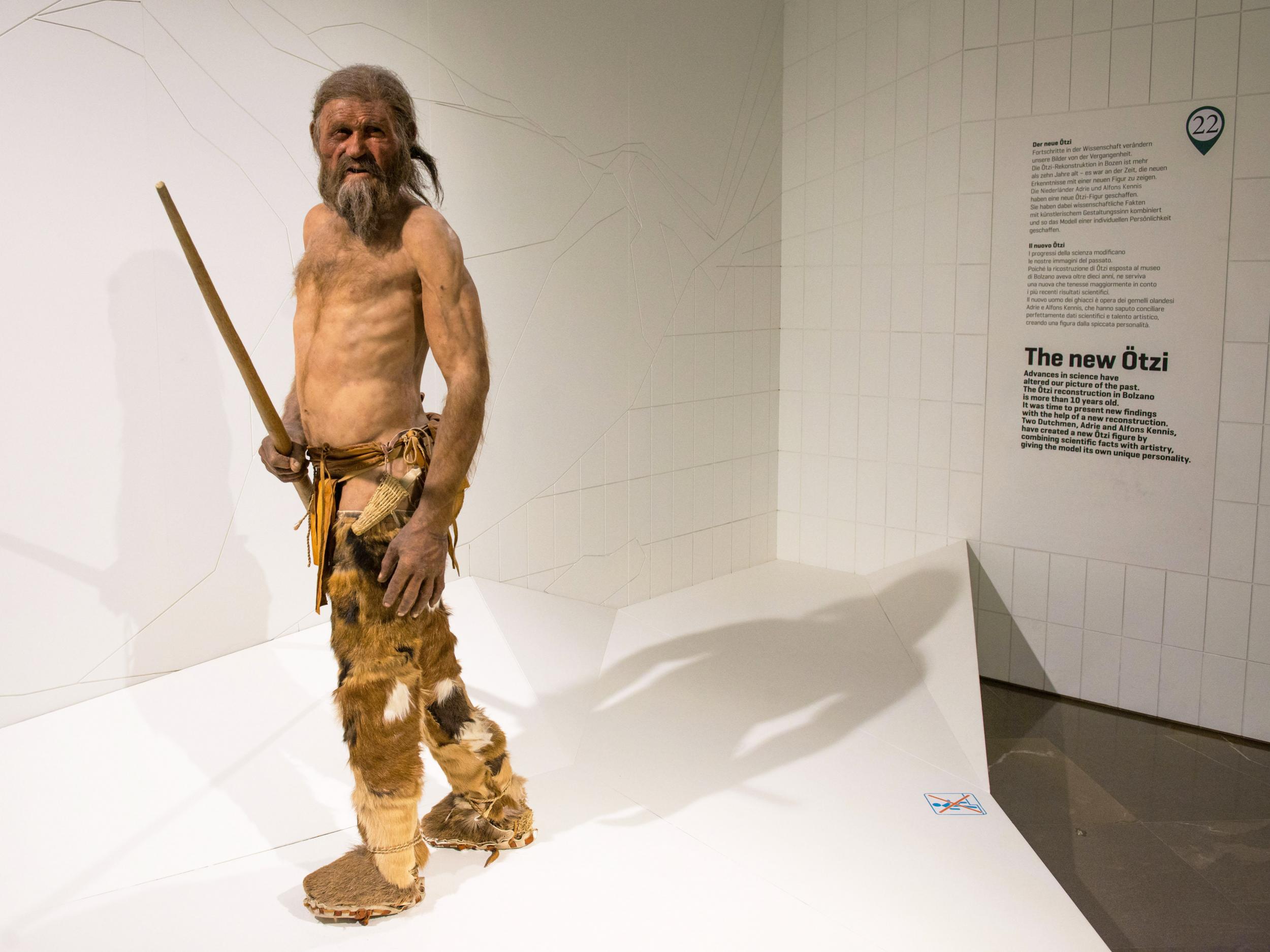

The final hours of the Iceman’s tools

In 1991, scientists in the Italian Alps came across a frozen, caramel-coloured corpse face down in the melting ice. They named him Ötzi, or the Iceman. Since that time, researchers have been learning more and more about the Iceman’s life in the Copper Age in Europe some 5,300 years ago.

The latest findings, published recently in the journal PLOS One, are focused on the tools he carried with him. A small dagger, a couple of arrowheads and a few other prehistoric possessions provide insight into their owner’s mysterious final days.

Dr. Ursula Wierer, an archaeologist from the provincial Department of Archaeology, Fine Arts and Landscape in Florence, Italy, says: “He cared about his tools,” adding that many showed signs of being resharpened or repaired.

Ötzi was in some sort of rush, says Wierer, as he did not have the time to construct a working bow or complete his other dozen arrowheads before his death.

Magnetic sense helps billions of moths on an Australian migration

Every spring in Australia, billions of bogong moths migrate from the arid plains of Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria to the meadows of the Australian Alps to escape the impending heat.

How these animals complete this epic journey to a place they have never been and back, has long been a mystery. But scientists have now discovered that bogong moths have a magnetic sense to help them.

In a paper published recently in Current Biology, they tested how the moths reacted to moving visual cues and magnetic fields in an outdoor flight simulator and found that the winged insects use magnetic fields like a compass.

While other animals like nocturnal songbirds and sea turtles are known to migrate by earth’s magnetic fields, the researchers say this is the first reliable evidence that insects can, too.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks