Science news in brief: From a lava lake to a dancing cockatoo

And other news from around the world

This cockatoo thinks he can dance

Watching Snowball the cockatoo dance to Queen’s “Another One Bites the Dust” has long been one of the joys of the internet.

The four-minute video has been viewed more than seven million times, and it’s probably generated at least that many grins. But when a small group of scientists first saw it a decade ago, they knew that it was more than entertaining. If it was real, it offered the first genuine support for a claim Darwin had made 148 years ago, but never proven: that animals perceived and enjoyed music as much as we did. Now, the team has published their findings in the journal Current Biology, showing that Snowball can not only groove to music without explicit training, but he’s got his own dance moves.

“This suggests that sensitivity to music or capacity for music or musicality is shared among more animals than only humans and might have a long evolutionary history,” said Henkjan Honing, a professor of music cognition at the University of Amsterdam, who was not involved in the research, but who paid off the earlier bet. He said research on Snowball’s dancing persuaded him that musicality is an inborn, biological ability, like language, rather than a learned one, like reading.

Whether musicality is embedded in biology is still hotly debated. “My dream for my career is to be able to answer it with some feeling of certainty,” said Aniruddh Patel, a professor at Tufts University near Boston, who has led the Snowball research.

“If musicality is something that our brain has been shaped to do, that does speak to people’s questions about what human nature is,” Patel said. The research also raises the question of whether humans have evolved brain specialisations for processing music, as we have for language.

Patel first saw Snowball on YouTube in 2008 and called Irena Schulz, who ran the shelter where the parrot lived. She had a background in biology and agreed to participate in a study. They tested Snowball’s ability to stick to the beat at 11 tempos. He isn’t perfect – rather like a toddler in a music class – but his movements sped up or slowed with the music.

Importantly from a scientific perspective, there was no human rocking out in the room with him, or feeding him treats to reward him for his dance moves. He did receive social rewards, like the verbal encouragement “good boy!”

Rat lungworm disease infects people but eludes researchers

A tropical parasite transmitted through rats and snails has caught the attention of health officials in Hawaii. But few scientists have studied the infection once it makes its way into humans, and researchers can’t say for certain whether the disease is becoming more widespread.

The parasite, Angiostrongylus cantonensis, typically resides in a rat’s pulmonary arteries and is commonly known as “rat lungworm”. When its eggs hatch, tiny larvae are shed in the animals’ faeces and eaten by snails or slugs. Those slugs, in turn, are often mistakenly eaten by people, on unwashed produce or in drinks that have been left uncovered.

Although the larvae can’t grow into adult worms in a human host, they still can cause complications including flu-like symptoms, headaches, stiff necks and bursts of nerve pain. MRI scans suggest that the worms can also enter the brain, leading to eosinophilic meningitis, which in rare cases can cause paralysis.

Doctors in the state have noted cases of rat lungworm disease since at least 1959. But it is difficult to diagnose. To better track it, and to identify areas that prevention efforts should target, the Hawaii Department of Health began monitoring rat lungworm infections about a decade ago. From 2007 to 2017, officials tallied 82 cases, two of which resulted in death. Another 10 cases were reported in 2018, and six more have been reported among visitors and residents already this year.

The east side of the Big Island, in particular, has become a hot spot for infections, according to a review of cases published July 8 in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Researchers are not sure why. Rats may be more numerous there, or more heavily infected, or more likely to cross paths with humans and infect them. Increased awareness about the disease may also have led to more infections being recognised than in the past.

Improved testing and increased awareness will “hopefully lead to a better understanding of any patterns of infection across our state,” said David Johnston, an epidemiologist with the Hawaii Department of Health who led the study.

But overall, the study did not find a rise in the number of cases across the state. Rat lungworm disease still affects relatively few people, causing from one to 21 cases each year. So any fluctuations in the number of cases can appear more dramatic than they actually are, Johnston said.

Why did this extinct bird have such a weird, long toe?

Some 99 million years ago, a small animal with a weird elongated toe died and became partially entombed in amber. Its lower leg and foot remained undisturbed in the hardened tree resin until amber miners eventually discovered the fossil in Myanmar’s Hukawng Valley in 2014. The preserved toe measures less than half an inch from knuckle to claw-tip, making it 41 per cent longer than the next longest digit on the animal’s foot. When traders showed the curious specimen to Chen Guang, a curator at China’s Hupoge Amber Museum, they suggested that it probably belonged to an extinct lizard.

Chen thought that the remains looked more like an avian species, so he looped in Lida Xing, a paleontologist at China University of Geosciences who specialises in Cretaceous birds.

A handful of Cretaceous bird fossils have been found in Burmese amber, but this is the first to be identified as a new species. Named Elektorornis (“amber bird”) chenguangi, the specimen is described in a study, led by Xing, published in Current Biology.

E. chenguangi was smaller than a modern sparrow and belonged to a family of birds called Enantiornithes, which was abundant during the Cretaceous period.

Its elongated toe structure has never been observed in other birds, living or extinct. Its foot also sported an unusual layer of bristled feathers, “unlike any adult bird known today,” according to Jingmai O’Connor, a co-author and paleontologist at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing.

Long toes are associated with arboreal animals that need a firm grip on tree branches. The bristles suggest that the bird’s foot also had a sophisticated sensory system. Xing’s team speculated that E. chenguangi may have used the long, sensitive digit to probe cracks in trees for insects and grubs, just as the aye-aye lemur uses a slim finger to extract food in modern Madagascar.

These sorts of special adaptations may have helped propel Enantiornithes to evolutionary success during the age of dinosaurs. At that time, Enantiornithes overshadowed Neornithes, the group that contains all modern avian species. But that abruptly changed when a huge asteroid hit Earth 66 million years ago.

Enantiornithes were wiped out along with the non-avian dinosaurs, while Neornithes went on to become the diverse group of birds – from ostriches to penguins, eagles to hummingbirds – that currently inhabits our planet.

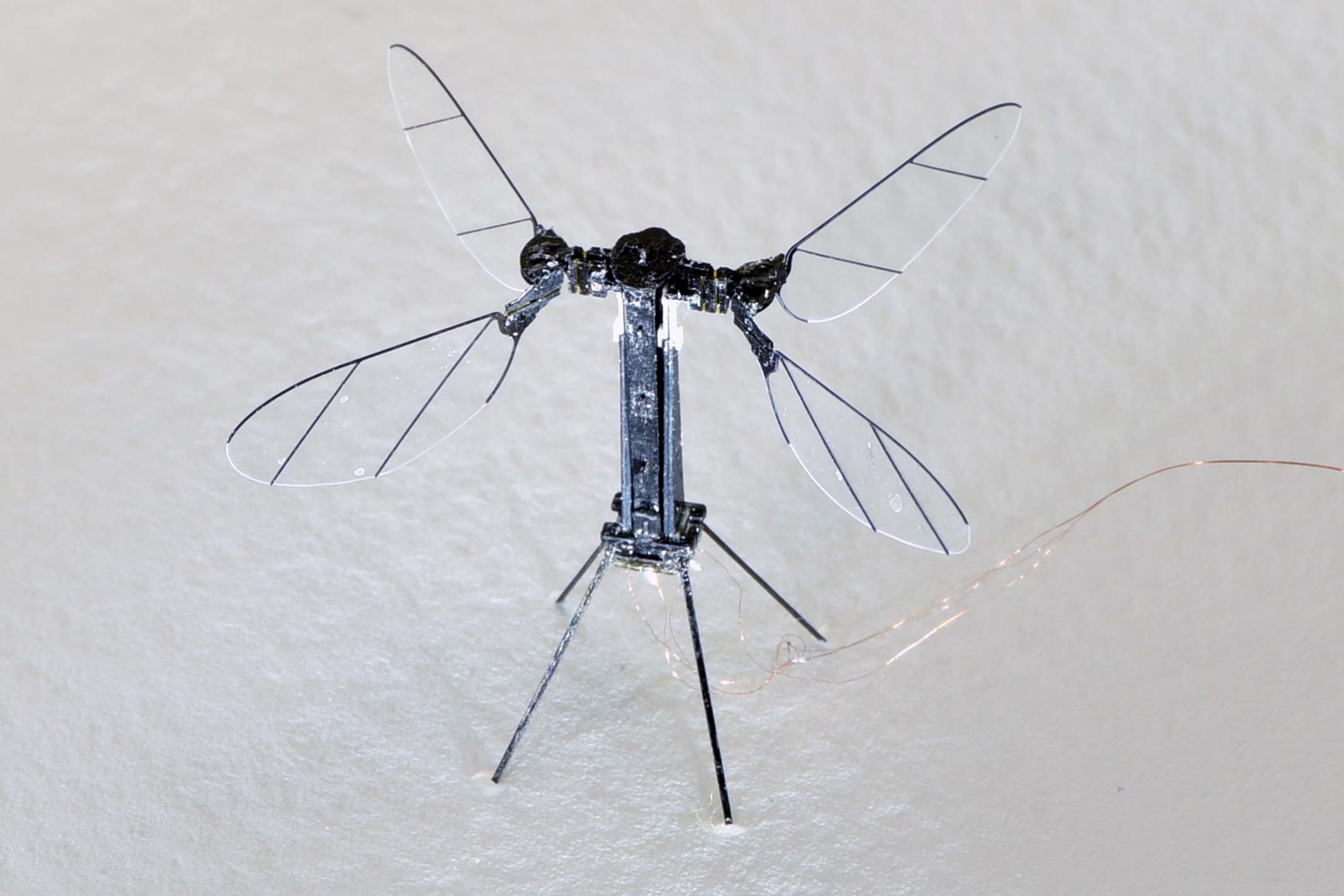

A robo-insect takes to the air

For years now, scientists have sought to build aerial robots inspired by bees and other flying insects. But they have always run into a fundamental problem: Flying takes a lot of energy.

Insects flap their wings, generating the thrust needed to move through the air by utilising the energy stored in strong muscles. Their robot doppelgangers must rely on batteries, which are less efficient and tend to be heavy, or must be hooked up externally.

Now researchers at Harvard University have built a new type of robot that is capable of true, untethered flight. The unit, called the RoboBee X-Wing, is equipped with four tiny wings made of carbon fibre and polyester, and even tinier photovoltaic cells.

In bright light, its solar cells generate about five volts of electricity, which a minuscule transformer then boosts to the 200 volts necessary for lift-off. When the high voltage is applied to two components called piezoelectric actuators, they bend and contract, much as an insect’s muscles would. This drives the flapping motion of the RoboBee’s wings.

Clever engineering keeps the device small and light – about one-quarter the weight of a paper clip. This allows the RoboBee to flit about freely, whereas previous iterations of the robot could only take off, land, or perch mid-flight while leashed to a power supply.

“We wanted to keep pushing the limit on how much power we could squeeze out of the artificial muscles in the robot, and how efficient we could make the whole system,” said Noah Jafferis, a postdoctoral engineer at Harvard and one of the leaders of the research.

Last month, Jafferis and his colleagues reported in Nature that the RoboBee is now able to match the thrust efficiency of similarly sized insects, such as bees.

So far, each of the RoboBee’s test flights have only lasted a couple seconds. One of the robot’s shortcomings is that it still can’t store energy. As soon as it flies out of a small, well-lit area, it slows down and falls to the ground.

But Helbling and Jafferis are confident that the robot could stay aloft for several minutes if its solar cells and circuits were given the proper tweaks.

A burning lava lake concealed by a volcano’s glacial ice

While Earth’s surface is peppered with volcanoes, lava lakes appear to be vanishingly rare. Popular imagery of volcanoes may imply that these crowning cauldrons of liquid fire are common, but there were thought to be only seven contemporary volcanoes on Earth with persistent lava lakes that have been seen to stick around beyond a single eruptive outburst.

Now, using 30 years of satellite observations, a group of scientists from University College London and the British Antarctic Survey has added an eighth volcano to that list: Mount Michael, a 3,250ft-high stratovolcano on Saunders Island, a frigid outpost 1,000 miles from Antarctica, the nearest major land mass.

Monitoring this molten reservoir may improve our ability to somewhat forecast the potential hazards from other volcanoes containing lava lakes that are closer to human populations, said Jani Radebaugh, an expert in planetary satellites at Brigham Young University who was not involved with the study.

Mount Michael is an active, sputtering volcano largely covered in glacial ice. Its slopes are dangerous, and its summit has never been reached. It’s also so far from civilization that “it’s almost like it’s on another planet,” said Rosaly Lopes, an expert in planetary and terrestrial volcanology at Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who was not involved with the study.

That meant that finding it required satellite observations and analyses. Starting in the 1990s and early 2000s, some orbital eyes spotted prolonged thermal anomalies that hinted at a lava lake’s existence, but couldn’t prove it. But improved satellite imagery from the Landsat, Sentinel-2 and the Terra missions and better processing techniques have allowed this lake to be conclusively identified in a report published this month in the Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. Its thermal signature could be seen throughout the observation period, suggesting the lake is probably persistent.

The team collected enough shots of the lake from 2003 to 2018 that clearly showed a crater floor containing a superheated lake 295 to 705 feet across. The lava is also 1,812 to 2,334F, with the higher end of that range about as hot as lava on Earth seems to get.

This discovery emphasises the geographic diversity of persistent lava lakes. Others have been found within Ethiopia’s Erta Ale, Antarctica’s Mount Erebus, the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Nyiragongo, Nicaragua’s Masaya, Vanuatu’s Mount Yasur and Ambrym and Hawaii’s Kīlauea.

Additional reporting: Robin George Andrews, Becky Ferreira and Karen Weintraub

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks