Science news in brief: From menace green crabs to the termites living without males

And a roundup of other stories from around the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Archaeologists use laser vision to unveil ancient Mayan Kingdom

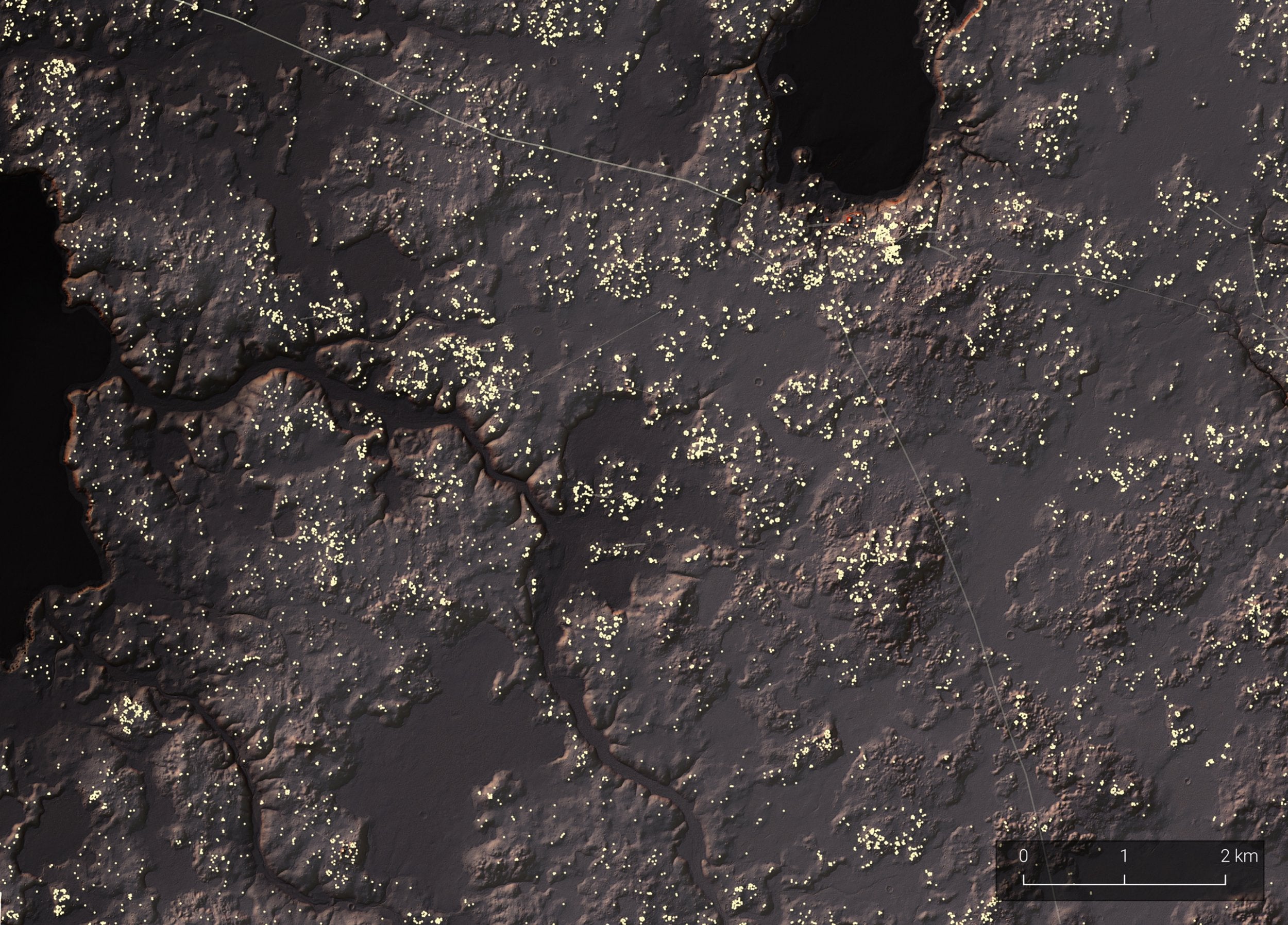

Hidden pyramids and massive fortresses in the jungle. Farms and canals scattered across swamplands. Highways traversing thickets of rain forest. These are among more than 61,000 ancient Mayan structures swallowed by overgrowth in the tropical lowlands of Guatemala that archaeologists have finally uncovered using a laser mapping technology called lidar.

The discoveries, published recently in Science, provide a snapshot of how the ancient Maya altered the landscape around them for more than 2,500 years from about 1000BC to AD1500, and may change what archaeologists thought they knew about aspects of the ancient society’s population size, agricultural practices and conflicts between warring dynasties.

The ancient Maya flourished in what is today southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize and western Honduras. They left behind a rich written history painted and inscribed on wood, stone and ceramics.

“You’re looking at a series of kingdoms all involved in this ‘Game of Thrones’ political story where they are marrying, fighting, killing each other and backstabbing,” says Thomas Garrison, an archaeologist at Ithaca College and an author of the paper. “Lidar reveals the stage in which these dramas recorded in texts played out.”

Lidar is similar to sonar or radar, but it uses bursts of laser light to map an area.

In 2016, Juan Fernández-Díaz, a senior researcher at the National Centre for Airborne Laser Mapping at the University of Houston, and his team flew over more than 800 square miles of forest in northern Guatemala in an airplane equipped with lidar. The plane was about 2,000 feet above the jungle canopy, and for every second they flew the lidar sent about half a million laser pulses.

The 3D map they made revealed new settlements with houses and temples, defensive fortifications like ditches and moats, as well as agricultural terraces and roads.

The team’s work was funded by Pacunam, a foundation that works to preserve Maya cultural heritage.

From the data, the team estimates there may have been about 7 million to 11 million people living in the central Maya lowlands during what was known as the Late Classic Period, which lasted from about AD650 to about AD800.

‘Highly aggressive’ green crabs from Canada menace Maine’s coast

In the mid-1800s, European green crabs hitched a ride on boats and came to the United States. But over the past few years, a genetically different European green crab from Nova Scotia, Canada – one that is more combative and more destructive of ecosystems – has appeared off the coast of Maine.

“To use nice words, I would simply describe them as highly aggressive,” says University of New England professor Markus Frederich. In the lab, he and his students use more colourful language while working with the crabs, which come at them, pincers up.

The aggressive nature of the Canadian hybrid, described as “the cockroach of the sea” poses another problem for Maine, which already struggles to defend its soft-shell clam population from Maine green crabs.

Green crabs slice through eelgrass, an important habitat for other sea creatures, Frederich says. Preliminary research shows that the aggressive crabs from Canada wreak more havoc on eelgrass and soft-shell clam populations compared with their Maine counterparts.

Attempts to reduce the impact of the crabs have included creating products out of them, such as commercial compost and food paste. Fences have also been placed in the water to protect soft-shell clam populations.

Brian Beal, a professor at the University of Maine at Machias, says the crabs from Canada have no native predator in North America, and only cold winters keep their population in check. Rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean “conditions are becoming more and more favourable for green crabs to survive and populate areas”, he says.

The aggressive green crabs have hurt the state’s $15m (£11.6m) soft-shell clam industry, and they are ravenous in their pursuit.

Killer whales face dire PCBs threat

Most people thought the problem of polychlorinated biphenyls – known as PCBs – had been solved. Some countries began banning the toxic chemicals in the 1970s and 1980s, and worldwide production was ended with the 2001 Stockholm Convention.

But a new study based on modelling shows that they are lingering in the blubber of killer whales – and they could end up wiping out half the world’s population of the whales in coming decades.

“It certainly is alarming,” says Jean-Pierre Desforges, a postdoctoral researcher at Aarhus University in Denmark and the lead author on the new study published recently in Science.

Whales sit at the top of their food chain. Chemicals like PCBs are taken up by plankton at the base of the food chain, then eaten by herring and other small fish, which are themselves eaten by larger fish, and so on. At each step in this chain, PCBs get more and more concentrated.

Killer whale populations in Alaska, Norway, Antarctica and the Arctic among other places, where chemical levels are lower, will probably continue to grow and thrive, the study found. But animals living in more industrialised areas, off the coasts of the United Kingdom, Brazil, Hawaii and Japan, and in the Strait of Gibraltar, are at high risk of population collapse from just the PCBs alone – not counting other threats.

The elephant bird regains its title as the largest bird that ever lived

Standing nearly 10 feet tall and weighing up to 1,000 pounds – or so researchers believed – this flightless cousin of the ostrich went extinct in the 17th century, thanks in part to humans stealing their massive eggs.

More recently, the bird’s designation as the heaviest in history was challenged by the discovery of the slightly larger, unrelated Dromornis stirtoni, an Australian flightless giant that went extinct 20,000 years ago.

But a new study seeks to restore the elephant bird’s heavyweight title. After taxonomic reshuffling and examination of collected elephant bird remains, researchers say that a member of a previously unidentified genus of the birds could have weighed more than 1,700 pounds, making it by far the largest bird ever known.

Over the centuries, scientists have competed to collect and display the largest elephant bird bones. But, “nobody’s done any real cohesive research on these birds”, says James Hansford, a palaeontologist at the Zoological Society of London and lead author of the study, resulting in a taxonomic muddle for the feathered giants. As a result, more than 15 elephant bird species had been identified across two genera.

Hansford travelled the globe with a measuring tape examining thousands of elephant bird bones. He then used data on modern birds and algorithms to help determine how large the birds might have grown.

His conclusion, published recently in the journal Royal Society Open Science, is that there were actually three genera of elephant bird rather than two, and four species rather than 15: Mulleornis modestus, Aepyornis hildebrandti, Aepyornis maximus and Vorombe titan.

One of those species, A maximus, had long been considered the heaviest elephant bird, until a British scientist in 1894 claimed to have discovered an even larger species, Aepyornis titan. Other researchers dismissed the finding, saying A titan was simply an unusually large member of the A maximus clan.

But Hansford reports that A titan is not only its own species but a separate genus of much larger elephant bird, as evidenced by the distinct size and shape of all three limb bones. He has named the species and genus Vorombe titan; vorombe is a Malagasy word meaning “big bird”.

Life without males? These termites are giving it a try

Often dismissed as pests, termites have been doing incredible things since the time of dinosaurs, maintaining complex societies with divisions of labour, farming fungus and building cathedrals that circulate air the way human lungs do.

Now, add “overthrowing the patriarchy” to that list.

In a study recently published in BMC Biology, scientists reported the first discovery of all-female termite societies. Among more than 4,200 termites collected from coastal sites in southern Japan, the researchers did not find a single male.

Toshihisa Yashiro, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Sydney and lead author of the paper, says he was utterly surprised by the discovery: “I got a headache, because we believed that having both males and females is the rule in termite societies.”

The complete loss of males is rare across the animal kingdom, especially in animals with advanced societies. All-female lineages have previously been documented in a few ant and honey bee species, but their colonies are already dominated by queens and female workers.

His team collected 74 mature colonies of Glyptotermes nakajimai, a termite that nests in dry wood, from 15 sites in Japan. Thirty-seven of the colonies were asexual and exclusively female, while the rest were mixed-sex. Egg-laying queens in asexual colonies stored no sperm in their reproductive organs and laid unfertilised eggs.

Genetic analyses suggested that the asexual termites evolved from ancestors that split from other G nakajimai around 14 million years ago. The asexual termites have an extra chromosome compared with the sexual ones, suggesting the two groups may now be diverging into different species, says Nathan Lo, an evolutionary biology professor also at the University of Sydney.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments