Science news in brief: From lizards re-evolving legs to how octopuses taste with their arms

And other stories from around the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How some skinks lost their legs and then evolved new ones

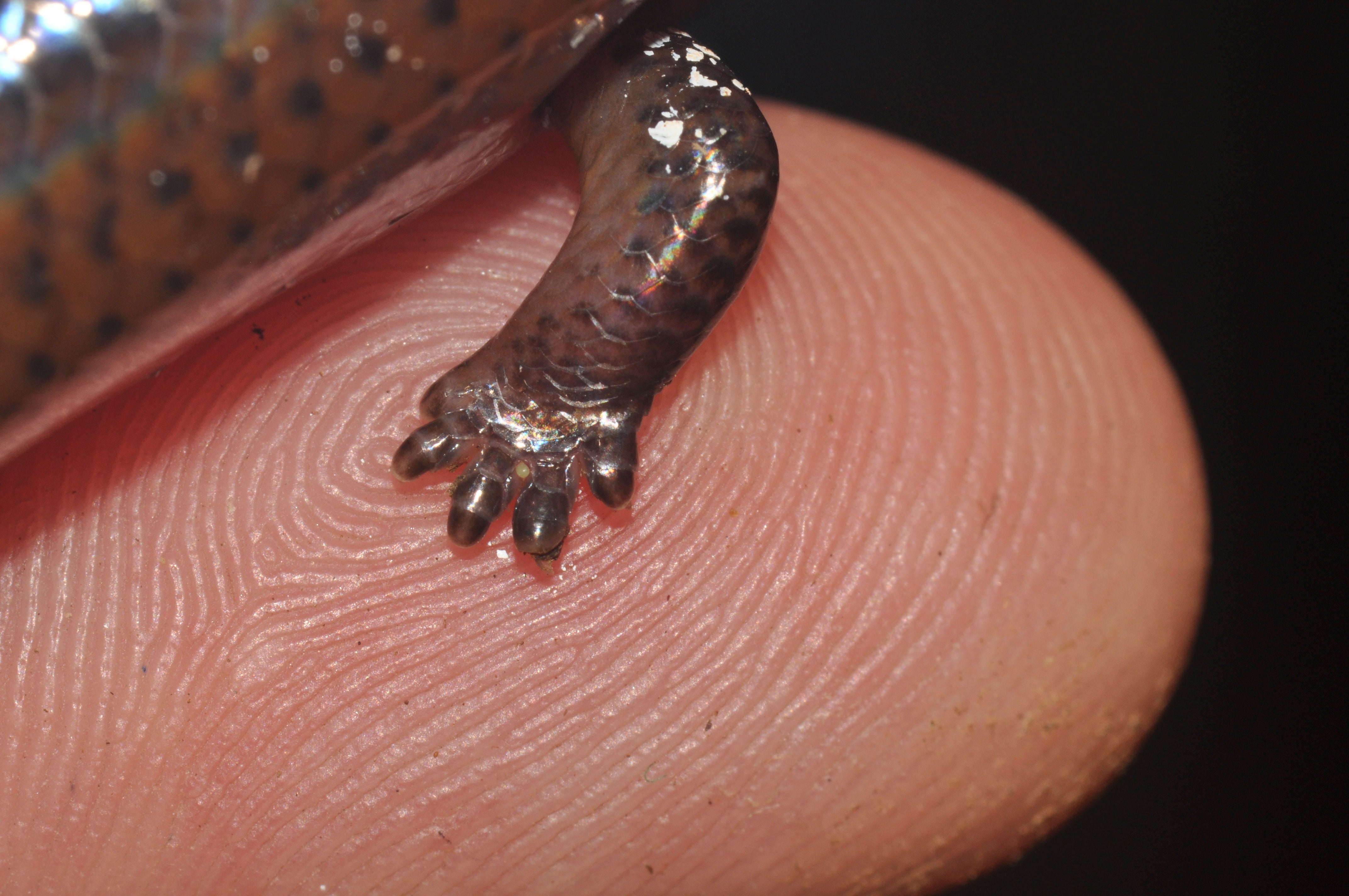

Skinks are lizards, but some species have lost their limbs over eons of evolution, giving them a snakelike look. However, other skinks whose ancestors jettisoned limbs have, for reasons still unknown, brought them back. They break an old rule of thumb in evolutionary biology, which holds that if you lose a complicated structure, you are unlikely to evolve it back.

A paper published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B shows that skinks with limbs move faster and burrow better than their limbless compatriots. And the timing of limb gains and loss across the family tree of skinks in the Philippines appears to sync up with shifts in the local climate, which could have changed the texture of the soil where they lived. As it grew drier, limbs disappeared, and as it grew damper, they sprouted back in some species, giving a rare glimpse into how, under the right evolutionary pressure, organisms can force limbs back into being.

On land, many legless creatures live in dry, sandy areas, says Philip Bergmann, a professor of biology at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, and an author of the new paper.

“A lot of people for decades, maybe even a century, have been suggesting that a snakelike form would be an adaptation for a burrowing lifestyle,” Bergmann says.

In Asian jungles, however, skinks with and without limbs coexist in the same damp, tropical environment.

To see how skinks in these habitats actually move, the team captured 147 individuals of 13 species. Some had no limbs, others had tiny ones, and others had fully formed legs and feet. The team found that skinks with limbs outperformed those without, moving and digging much faster. The limbless animals had their own manner of surviving in the forest, creeping slowly and keeping well out of sight rather than relying on speed.

Overlaying a reconstruction of the climate, based on published work by paleoclimate researchers, on the branching tree that contained all these species revealed interesting patterns. Sixty million years ago, when the skinks first lost their limbs, the area was much drier. Twenty million years ago, when some of them brought their limbs back, the climate had shifted to be wet and monsoonal.

“The climate in the past seems to correlate pretty nicely with our hypothesis,” Bergmann says. Perhaps in wetter climes, limbs had advantages they had not had before.

— Veronique Greenwood

Ready to mate? Take off your mask, one bat says

Wrinkle-faced bats are full of contradictions. Despite their fruit-heavy diet, they’re not considered to be fruit bats. They’re classified as leaf-nosed bats, even though they lack the group’s characteristic nose.

Even their Latin name, Centurio senex, which loosely translates as “the 100-year-old-man”, is misleading. The bats’ persistently pruned-up mugs belie their ultrafast reflexes, powerful bites and, apparently, their serious sex appeal.

Bernal Rodriguez Herrera, a bat biologist at the University of Costa Rica, affectionately calls the males of the species “masked seducers”. In a paper published in PLOS ONE, he and his colleagues describe some of the bats’ sexual shenanigans, which apparently include serenading potential mates en masse. If confirmed, the behaviour observed by the researchers could be one of the rarest of courtship rituals.

Part of the amorous affair, the researchers report, seems to involve the deliberate flexing of the furry folds of skin that cradle the bats’ chins. Using their thumbs, bats can raise the fluffy structures over their faces at will like neck gaiters. The extra skin is found only on males – a hint that it might have evolved to make the ladies go wild.

Before his study’s data was collected, Rodriguez Herrera had only logged about 15 wrinkle-faced bat sightings in his 30-year career. But in September 2018, he ventured into a particularly sweltering sector of the Costa Rica rainforest, where he discovered dozens of wrinkle-faced males.

On 13 nights, Rodriguez Herrera and his colleagues diligently monitored the bats. During the twilight hours, the males, hanging by their feet, rubbed their wingtips against each other. When another bat approached, the males would beat their wings and emit a series of calls, ending in a low-frequency whistle.

The researchers propose that these serenades might be indicative of a courtship strategy called a lek: a group of males who loosely convene in the same region, called a mating arena, to competitively strut their stuff. Visiting females select a small subset of the most show-offy suitors, copulate with them and leave.

It’s still a mystery what role the bats’ masks play, if any, in luring mates. Rodriguez Herrera notes that the males vocalise almost exclusively with the skin flaps up, suggesting the structures might modulate sound. The bright white masks could also serve as a visual beacon for females, or have some effect on the musky, skunkish odours that males reportedly release around their chins.

— Katherine J Wu

A record of horseback riding, written in bone and teeth

The advent of horseback riding transformed our ancestors’ lives, irrevocably changing how they migrated, fought wars and traded. Now, researchers have found the oldest direct evidence of horseback riding in China, which could help unlock how the civilisation was affected by a newfound ability to get around on four legs.

While neighbouring civilisations — such as those in the area now known as Mongolia — had been riding since roughly 1200 BC, the timing and details of the rise of horsemanship in China have long remained murky, says William Taylor, an archaeologist at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History in Boulder, Colorado.

But the new study to which he contributed, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests that mounted equestrianism in China goes back as far as 350 BC. That is consistent with the belief that horseback riding enhanced Chinese military might and contributed to the formation of the first unified empire during the Qin dynasty in the third century BC.

Taylor and his colleagues, led by Yue Li and Jian Ma of Northwest University in Xi’an, China, analysed eight largely intact horse skeletons roughly 2,400 years old excavated in northwestern China.

The team started by examining the horses’ vertebrae. Of the roughly 240 vertebrae the team studied, over 60 per cent exhibited abnormalities such as excessive bone growth, fusion and fractures. These pathologies were most common in the lower back.

That’s telling, says Katherine Kanne, an archaeologist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, who was not involved in the research. A horse’s lower back bears most of the stress from being ridden, she says.

Taylor and his collaborators next studied the skulls of seven of the horses. They found that six exhibited pronounced grooves in the bones of their nose. This pathology can arise in a horse that was worked strenuously, Taylor says.

The scientists then analysed the horses’ teeth. Taylor and his colleagues found that of the six horses with intact teeth, all showed signs of abrasion on their lower second premolars, consistent with traumatic contact between a bit and the horse’s teeth, Taylor says.

Taken together, these bone and tooth abnormalities are textbook examples of what happens when horses are ridden heavily, says Alan Outram, an archaeologist at the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom, who was not involved in the research. “There’s no question that these horses are riding horses.”

— Katherine Kornei

When it comes to octopuses, taste is for suckers

Scientists have known for years that octopuses can taste what their arms touch. Now, a team of Harvard biologists has cracked some of the code behind this feel-and-feed feat.

The cells of octopus suckers are decorated with a mixture of tiny detector proteins. Each type of sensor responds to a distinct chemical cue, giving the animals an extraordinarily refined palate that can inform how their agile arms react, jettisoning an object as useless or dangerous, or nabbing it for a snack.

The study, published in the journal Cell, “really nails the molecular basis for a new sensory system,” says Rebecca Tarvin, a biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, who wrote a commentary on the findings but was not involved in the research. “This was previously kind of a black box.”

Though humans have nothing quite comparable in their anatomy, being an octopus might be roughly akin to exploring the world with eight giant, sucker-studded tongues, says Lena van Giesen, the study’s lead author. “Or maybe it feels totally different,” she says. “We just don’t know.”

Scientists have found the cephalopods can wield tools, puzzle their way through mazes and mischievously squirt water at their caretakers. Housed in labs, they’ll also try to liberate themselves from their tanks, unless the lids are weighted down with bricks and lined with Velcro — a textured material that the animals apparently dislike, says Nicholas Bellono, a co-author of the study.

In the lab, Van Giesen, Bellono and their team studied cells extracted from suckers on the arms of California two-spot octopuses.

Some cells, they discovered, were there to detect only touch. Another population of cells, called chemoreceptors, instead detected chemicals, such as those that imbued fish with flavour.

A series of genetic experiments then revealed that the surfaces of these taste-tuned cells were covered with different types of proteins. By mixing and matching these proteins, cells could develop their own unique tasting profiles, allowing the octopus’s suckers to discern flavours in fine gradations, then shoot the sensation to other parts of the nervous system.

It seems that octopuses have “a very detailed taste map of what they’re touching,” Tarvin says. “They don’t even need to see it. They’re just responding to attractive and aversive compounds.”

The octopus palate hasn’t made these animals terribly picky. They eat fish, crabs, snails, other octopuses – “everything they can find, really,” Van Giesen says.

— Katherine J Wu

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments