Robotic arm named after Luke Skywalker enables amputee to touch and feel again

Recipient Keven Walgamott says he was almost brought to tears by ‘amazing’ new technology

A robotic arm which is controlled by thought has enabled an amputee to touch and feel again.

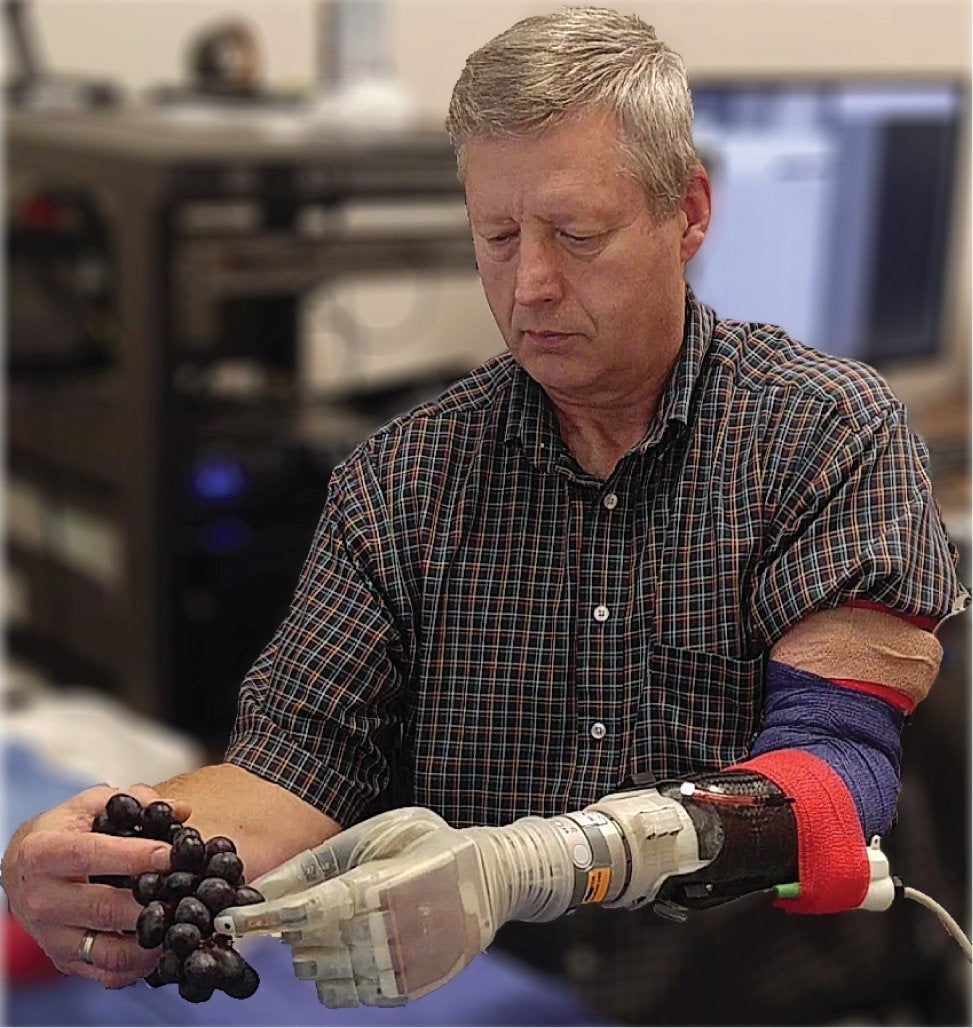

It is so sensitive that recipient Keven Walgamott plucked grapes without crushing them, peeled a banana and was even able to send texts.

The estate agent could also pick up an egg without breaking it, hold his wife’s hand and put on his wedding ring.

The motorised device has been named Luke after the prosthetic arm used by Star Wars character Luke Skywalker in The Empire Strikes Back.

Study leader Professor Gregory Clark, a biomedical engineer at the University of Utah, said: “One of the first things he wanted to do was put on his wedding ring. That’s hard to do with one hand. It was very moving.”

Mr Walgamott also successfully performed several tasks, including some he had previously found difficult, such as putting a pillow in a pillowcase.

The prosthetic hand and fingers are controlled by electrodes implanted in the patient’s muscles.

A portable prototype developed by the University of Utah team is connected to a computer on the wearer’s belt – providing complete freedom to use it anywhere.

Mr Walgamott, who is from Utah, said when he shook his wife by the hand the sensation in the fingers was similar to that of an able-bodied person.

The sense of touch apparently means users can distinguish between different surfaces. This is because they “feel” objects via sensors in the hand that feed impulses to the nerves in his arm.

After using the Luke arm for the first time, Mr Walgamott said: “It almost put me to tears. It was really amazing. I never thought I would be able to feel in that hand again.”

He is one of seven test subjects, and lost his left hand and part of the arm in an electrical accident in 2002. He is among 1.6 million amputees in the US, among whom depression and anxiety are common.

The hand, which moves with the person’s thoughts, acts as a “closed loop”, meaning it also prevents phantom pain – a common phenomenon in which amputees imagine the injured limb is still there.

So, when picking up the egg, Mr Walgamott’s brain could tell it not to squeeze too hard. The technology mimics the way a human hand feels objects by sending the appropriate signals to the brain.

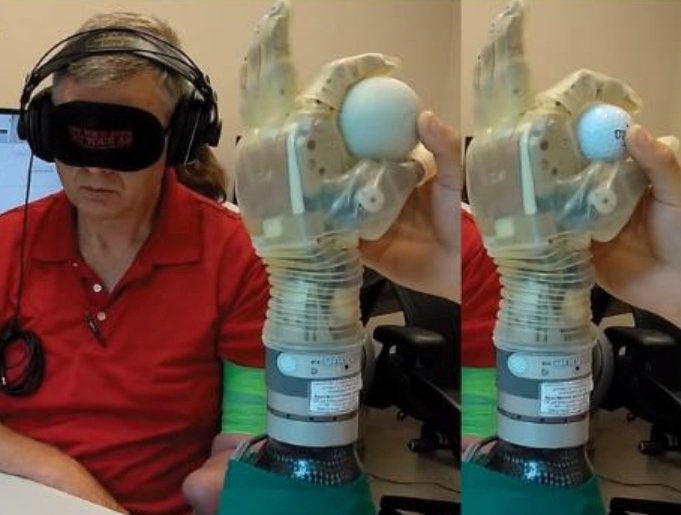

In experiments, Mr Walgamott was able to report the size, texture and type of different objects even while blindfolded and wearing headphones.

He was able to feel up to 119 perceptions ranging from pressure to vibration. He could identify and handle objects faster and more accurately than with any other system of this kind.

The 14-month study published in Science Robotics builds upon previous work demonstrating the potential of biologically inspired sensory feedback systems to restore natural “feeling” in the phantom hands of amputees.

While current prosthetics can replace lost motor functions, users still express the desire to have their artificial limb feel more natural.

Study co-author Jacob George, a doctoral student in Professor Clark’s lab, said: “We changed the way we are sending that information to the brain so that it matches the human body.

“And by matching the human body, we were able to see improved benefits. We are making more biologically realistic signals.”

It means an amputee wearing the prosthetic arm can sense the touch of something soft or hard, understand better how to pick it up and perform delicate tasks.

These would otherwise be impossible with a standard prosthetic with metal hooks or claws for hands.

The Luke arm was created by New Hampshire-based Deka Research and Development Corp.

It is made mainly of metal motors and parts, with a clear silicon “skin” over the hand, and is powered by an external battery and wired to a computer.

Meanwhile, Professor Clark and colleagues have come up with a system that lets the device tap into the wearer’s nerves.

These act like “biological wires” that send signals to the arm to move. It does this thanks to an invention by Utah’s Professor Richard Normann called the Utah Slanted Electrode Array.

A bundle of 100 tiny electrodes and wires are implanted into the amputee’s nerves in the forearm and connected to a computer outside the body.

The array interprets the signals from the still-remaining arm nerves and the computer translates them to digital signals that tell the arm to move.

But it also works the other way. To perform tasks such as picking up objects requires more than just the brain telling the hand to move.

The prosthetic hand must also learn how to feel the object in order to know how much pressure to exert because you can’t figure that out just by looking at it.

First, the prosthetic arm has sensors in its hand that send signals to the nerves via the array to mimic the feeling the hand gets upon grabbing something.

But equally important is how those signals are sent. It involves understanding how your brain deals with transitions in information when it first touches something.

Upon first contact of an object, a burst of impulses runs up the nerves to the brain and then tapers off. Recreating this was a big step.

Professor Clark said: “Just providing sensation is a big deal, but the way you send that information is also critically important, and if you make it more biologically realistic, the brain will understand it better and the performance of this sensation will also be better.”

His team used mathematical calculations along with recorded impulses from a monkey’s arm to create an approximate model of how humans receive these different signal patterns. That was then implemented into the Luke arm system.

A completely portable version is now being developed that does not need to be wired to a computer outside the body. Instead, everything would be connected wirelessly, giving the wearer complete freedom.

The work has so far only involved amputees who lost arms below the elbow, where the muscles to move the hand are located, but it could also be adapted for those who lost their arms above the elbow, Professor Clark said.

He hopes by next year three test subjects will be able to take the arm home to use, pending government approval.

SWNS

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks