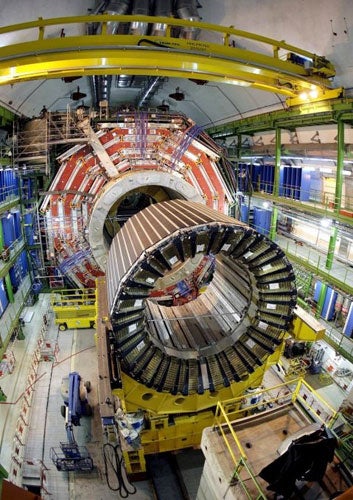

Quest for 'Big Bang' delayed by fault in Hadron Collider

Overheated magnets have delayed the next stage of the £5bn experiment to recreate the Big Bang, scientists working on the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva have said.

The super-cooled magnets, which steer hair-width beams of particles travelling at almost the speed of light around a 27km tunnel, rose in temperature by up to 100C last night, forcing engineers to shut down the machine.

The Swiss fire brigade were called after a tonne of liquid helium also leaked into the tunnel.

Scientists had hoped to move on to the next stage of the project – making the beams collide head-on – next week, but a spokesman for Cern, the French acronym for the European Organisation for Nuclear Research, told the BBC that it would be difficult if not impossible to do so.

Although the failure was "not good news", problems were expected during testing, he added.

Workers will spend the weekend assessing the damage, which is expected to put back the next stage of the experiment by at least a week.

The problem, which occurred during final tests of the facility's electrical circuits, was the latest in a series of setbacks since the LHC was switched on and the first beams fired around the subterranean loop on 10 September. On Thursday engineers had to replace a faulty transformer.

The fault, known as a quench, occurred at 9.30am yesterday in one of the final sections of the tunnel, the BBC said. The temperature of about 100 magnets, which must be supercooled to 1.9C above absolute zero, rose by up to 100C and vacuum conditions in the tunnel were also lost.

The experiment is the most expensive in history, and scientists hope to crack the secrets of the universe by recreating the moment 13.7 billion years ago when it was formed. It is believed that for a trillionth of a second, everything was molten plasma which cooled to create the universe. The collision of the beams whizzing around the LHC should create 100,000 times more heat than the Sun, for a fraction of a second, in an area a billion times smaller than a speck of dust.

Some groups feared that the LHC would create a black hole, destroying the planet, and took their case to have the experiment stopped to the European Court of Human Rights. They failed in their bid, and with the click of a mouse, the first beams were sent around the LHC as planned 10 days ago.

The LHC – named after a hadron, which is a type of particle – could throw up a number of potentially revolutionary discoveries. Scientists know that visible matter makes up only 5 per cent of the observable universe, and hope their experiments will help fill in some of the void in their knowledge. The machine could, within weeks, produce particles of dark matter, which scientists say is made up of strings of skeleton-like particles stretching through the universe, making up 25 per cent of it. The remaining 70 per cent of the universe is dark energy, which drives the expansion of the cosmos.

Another of the researchers' principle aims is to try to find the Higgs boson, or "God particle", which is crucial to the understanding of the origin of mass. It is named after Peter Higgs, a physicist from the University of Edinburgh. Researchers using an earlier model of the collider in 1996 believed they had caught a glimpse of a Higgs boson.

The UK is one of 20 countries to have funded the project.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks