Dogs evolved ‘puppy dog eyes’ to help them get on with humans, study finds

‘When dogs make the movement, it seems to elicit a strong desire in humans to look after them,’ says Dr Juliane Kaminski

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dogs evolved "puppy dog eyes" to help them get on better with humans, according to a new study.

During domestication, dogs developed a facial muscle allowing them to raise the inner part of the eyebrows – giving them “sad eyes”. Wolves do not have this muscle and the only dog species without it is the Siberian husky, one of the most ancient breeds.

Scientists at the University of Portsmouth carried out the study comparing the anatomy and behaviour of dogs, which were first domesticated from wolves 33,000 years ago.

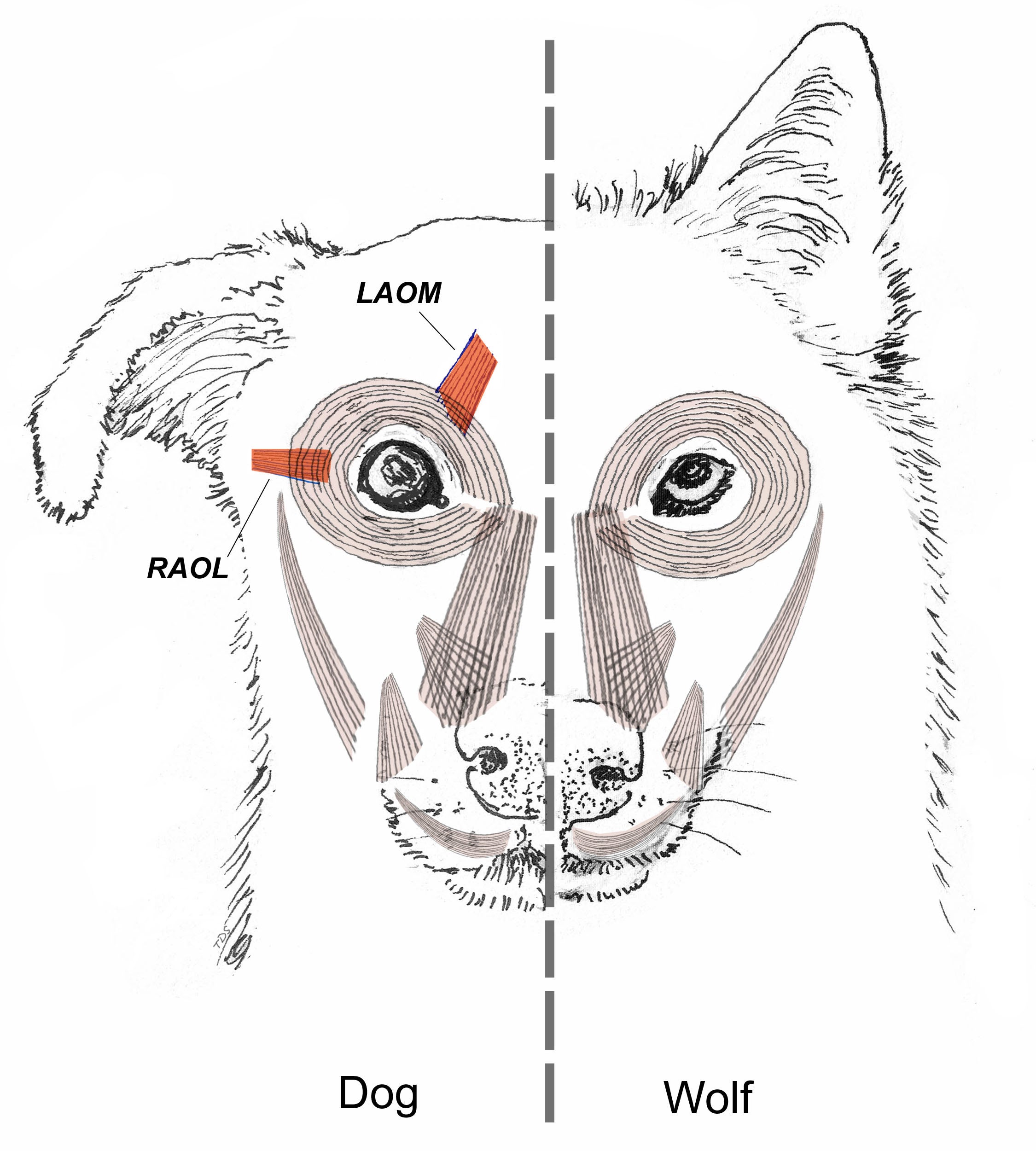

They found that the facial musculature of wolves and dogs was similar, except above the eyes. Dogs have solid muscle structure around their eyes while wolves only have an "irregular cluster of fibres".

Scientists say the eyebrow-raising movement triggers a nurturing response in humans because it makes the dogs’ eyes appear larger, more infant-like and also resembles a movement humans produce when they are sad.

The study compared the facial anatomy of four wild wolves and six domestic dogs. Researchers also carried out a behaviour analysis of nine wolves and 27 shelter dogs.

Psychologist Dr Juliane Kaminski, who led the research published in the American journal PNAS, said: “The evidence is compelling that dogs developed a muscle to raise the inner eyebrow after they were domesticated from wolves.

“The findings suggest that expressive eyebrows in dogs may be a result of humans’ unconscious preferences that influenced selection during domestication.

“When dogs make the movement, it seems to elicit a strong desire in humans to look after them. This would give dogs that move their eyebrows more a selection advantage over others and reinforce the ‘puppy dog eyes’ trait for future generations."

Dr Kaminski added that the brow movement creates the “illusion of human-like communication”.

Her previous research showed that dogs moved their eyebrows significantly more when humans were looking at them.

Lead anatomist Professor Anne Burrows from Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, who co-authored the new paper, said: “To determine whether this eyebrow movement is a result of evolution, we compared the facial anatomy and behaviour of these two species and found the muscle that allows for the eyebrow raise in dogs was, in wolves, a scant, irregular cluster of fibres.

“The raised inner eyebrow movement in dogs is driven by a muscle which doesn’t consistently exist in their closest living relative, the wolf.

“This is a striking difference for species separated only 33,000 years ago and we think that the remarkably fast facial muscular changes can be directly linked to dogs’ enhanced social interaction with humans.”

Anatomist Adam Hartstone-Rose of North Carolina State University said: “These muscles are so thin you can literally see through them – and yet the movement that they allow seems to have such a powerful effect it appears to have been under substantial evolutionary pressure.

“It is really remarkable that these simple differences in facial expression may have helped define the relationship between early dogs and humans.”

Additional reporting by PA

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments