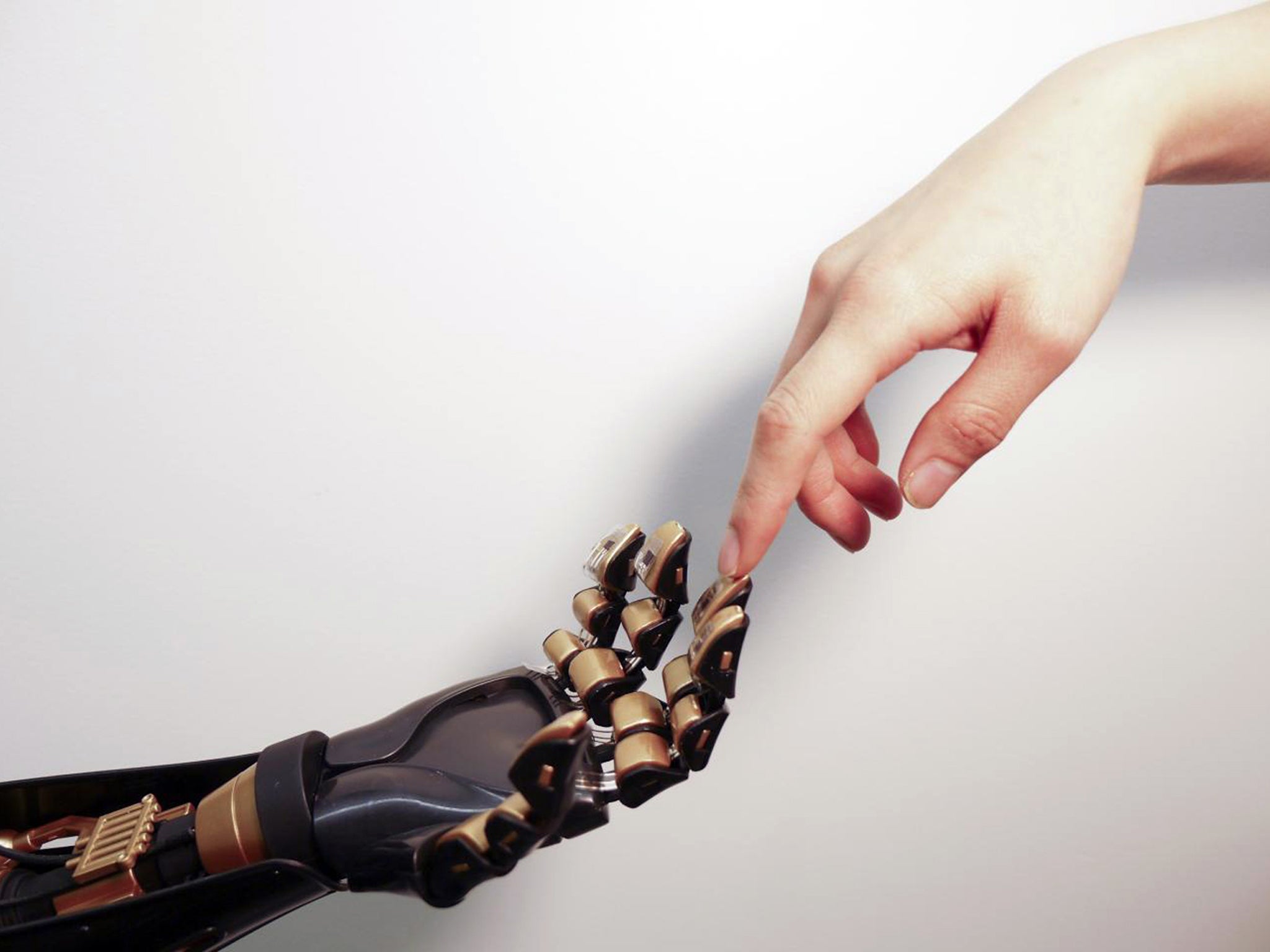

Prosthetic limbs could soon 'feel' after scientists develop skin that can sense touch

Researchers have made a major breakthrough in attempts to mimics the skin’s ability to sense touch, temperature and pain

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Prosthetic limbs could soon be designed with a sense of touch, after scientists developed a revolutionary plastic “skin”.

After a decade of study researchers from Stanford University in California have made a major breakthrough in attempts to mimics the skin’s ability to sense touch, temperature and pain.

The plastic skin is made of two layers. The top layer creates a sensing mechanism, while the bottom layer transmits electrical signals into biochemical stimuli for nerve cells to receive.

It is able to detect pressure over the same range as human skin, from a light finger tap to a firm handshake.

“This is the first time a flexible, skin-like material has been able to detect pressure and also transmit a signal to a component of the nervous system,” said Professor Zhenan Bao from the university’s department of chemical engineering, who led the 17-person research team.

The team at Stanford first used plastic as a pressure sensor five years ago, by measuring the natural springiness of their molecular structures. Now though, they have exploited this by scattering billions of one-atom thick grapheme tubes through the plastic.

Putting pressure on the plastic squeezes the tubes closer together and enables them to conduct electricity. This allows the plastic skins to mimic human skin, which transmits pressure information as short pulses of electricity, similar to Morse code, to the brain.

Professor Bao’s work, published in the journal Science, takes another step toward her ultimate aim of creating a fully flexible electronic fabric which can be embedded with sensors and cover a prosthetic limb to replicate some of the skin’s sensory functions.

“We have a lot of work to take this from experimental to practical applications,” Professor Bao added.

“But after spending many years in this work, I now see a clear path where we can take our artificial skin.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments