Professor Heinz Wolff: Bioengineering pioneer and TV presenter, dies aged 89

Renowned scientist was face of long-running BBC programme The Great Egg Race

Professor Heinz Wolff, a bioengineering pioneer and TV presenter, has died aged 89.

The renowned inventor and social reformer suffered heart failure on 15 December, his family said in a statement released through Brunel University London.

Wolff was a former adviser to the European Space Agency and presented BBC2’s long-running science show The Great Egg Race from 1977 to 1986, with his trademark bow tie, German accent and energetic persona endearing him to viewers.

He came to Britain as a an 11-year-old Jewish refugee, with his father and other relatives, from Berlin in September 1939, on the day the Second World War broke out.

He attended school in Oxford before working in haematology at the city’s Radcliffe Infirmary, where he invented a machine for counting patients’ blood cells, and graduated from University College London with a first-class degree in physiology and physics.

Much of his early career was spent in bioengineering, a discipline he established and named, which seeks to solve real-world problems using scientific concepts.

Wolff founded the Brunel Institute for Bioengineering in 1983 after 30 years working for the Medical Research Council. He later became an emeritus professor, working on a time-backing scheme which aimed to solve societal issues connected to the elderly population.

“Working with Heinz was like being at the centre of an ideas factory,” said Dr Gabriella Spinelli, his colleague on the scheme. “He was fiercely curious and always had new avenues to explore.”

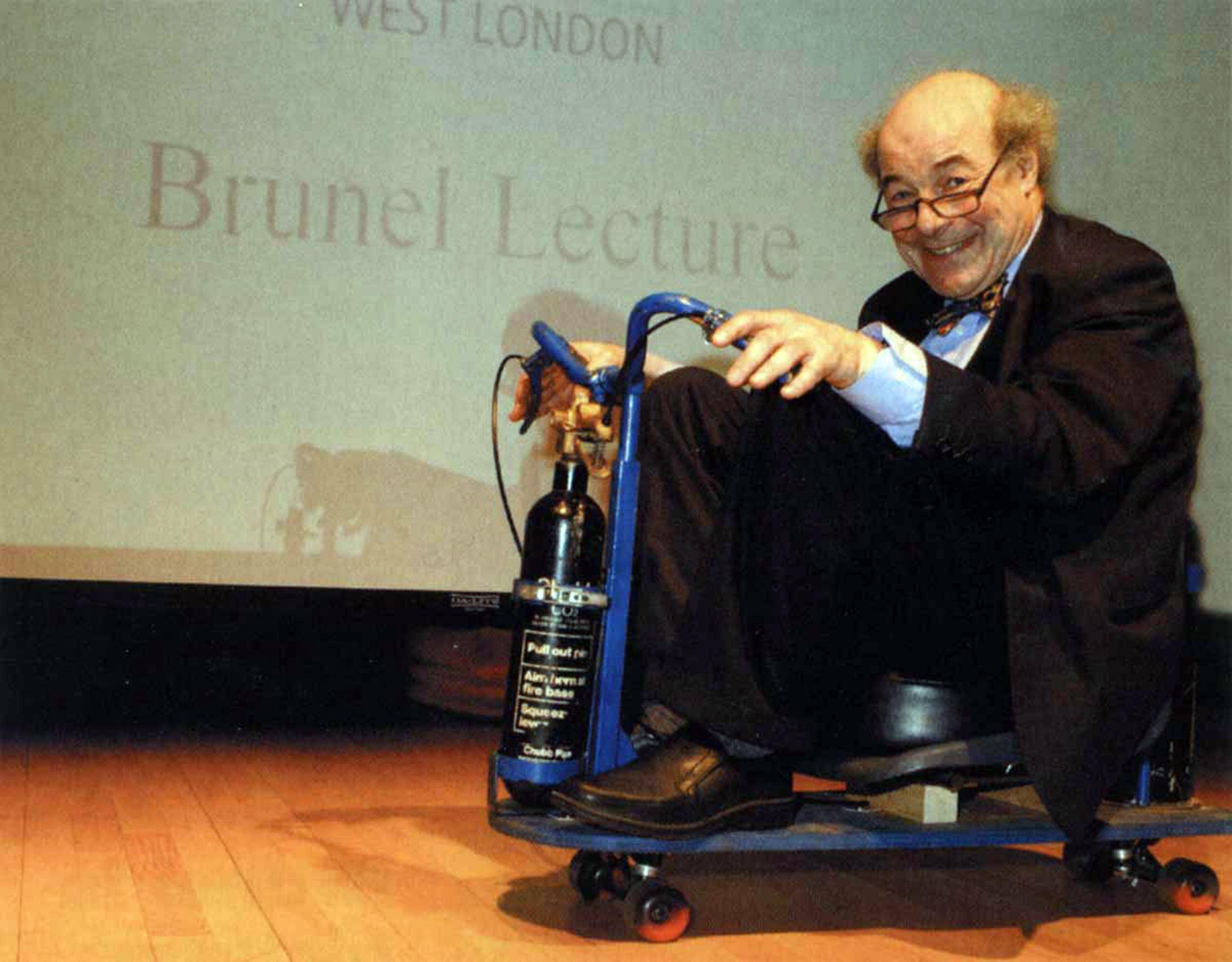

Colleagues at Brunel also recalled his penchant for practical jokes, including arriving at his 80th birthday party celebrations on a scooter propelled by fire extinguishers.

Close friend Professor Ian Sutherland, who took over directorship of the institute when Wolff retired in 1995, said: “Heinz was a most inventive and inspirational leader.

“There was nothing he loved more than having a team of people around him devising completely new ways of doing things.”

Sporting a bow tie and tufts of hair above the ears, Wolff became known to British television audiences in the 1970s and 1980s on the The Great Egg Race, which encouraged teams to invent useful objects out of limited resources.

His on-screen career began in 1966 on Panorama with Richard Dimbleby, where he produced a radio pill that could measure pressure, temperature and acidity in the gut.

Speaking in 2016, he recalled: “Richard swallowed one and when I gently poked him, the radio receiver squealed appropriately. The BBC had faith in me because I didn’t need a script and I was comfortable talking in front of a camera lens.”

Alongside his regular television appearances, Wolff’s scientific endeavours would continue to flourish.

He was made an honorary member of the European Space Agency in 1975. His research into how human beings could survive in hostile environments culminated in his co-founding of Project Juno which, in 1991, led to Dr Helen Sharman becoming the first British astronaut and the 15th woman in space, when she spent eight days in orbit on the Russian Mir space station.

Wolff had honorary doctorates from several universities, as well as fellowships of the Biological Engineering Society, the Institution of Electrical Engineers, the Institute of Biology, the Royal College of Physicians and the Royal Society of Arts.

He was awarded the Edinburgh Medal for outstanding contribution by a scientist to society in 1992.

Wolff was also a strong supporter of local charities, including over 25 years as a trustee and then as Life President of the Hillingdon Partnership Trust.

Professor Julia Buckingham, vice-chancellor and president of Brunel University London, said: “Heinz’s remarkable intellect, ideas and enthusiasm combined to make him the sparkling scientist we will so fondly remember.

“He was a wonderful friend and supporter to staff and to students – and an inspiration to all of us.”

Wolff was married to Joan until her death in 2014, and had two sons and four grandchildren.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks