First human genome from Pompeii sequenced

The remains belonged to a man who was aged between 35 and 40 years at the time of the eruption that wiped out Pompeii.

Researchers have successfully sequenced the human genome – DNA blueprint – of a man who died in Pompeii after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Before this only short stretches of DNA from Pompeiian human and animal remains had been sequenced.

Researchers believe this is the first successfully sequenced Pompeian human genome.

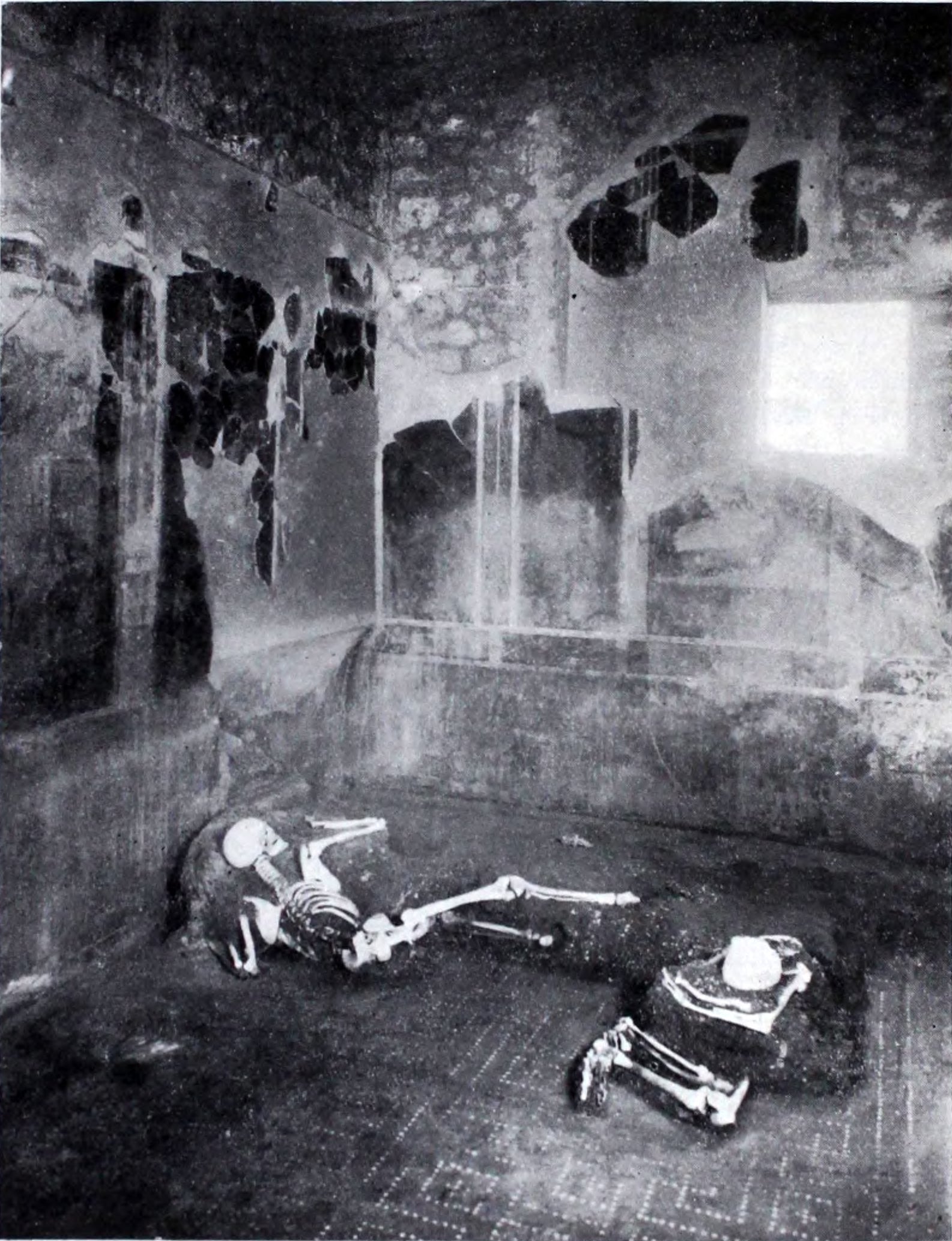

The remains of two individuals who were found in the House of the Craftsman in Pompeii were examined by researchers who extracted their DNA.

To our knowledge, our results represent the first successfully sequenced Pompeian human genome

The shape, structure, and length of the skeletons indicated that one set of remains belonged to a man who was aged between 35 and 40 years at the time of his death, while the other belonged to a woman aged over 50.

While the scientists were able to extract and sequence ancient DNA from both individuals, they were only able to sequence the entire genome from the male’s remains.

A comparison of his DNA with that of 1,030 other ancient and 471 modern western Eurasian people, suggested that the man’s DNA shared the most similarities with modern central Italians and other people who lived in Italy during the Roman Imperial age.

Further analysis of his DNA identified groups of genes commonly found in people from Sardinia, but not among other people who lived in Italy during the Roman Imperial age.

According to the researchers, this suggests that there may have been high levels of genetic diversity across the Italian Peninsula during this time.

They also identified sequences that are commonly found in Mycobacterium, the group of bacteria that the tuberculosis-causing bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis belongs to.

This suggests the man may have been infected with tuberculosis before he died.

According to the scientists, it may have been possible to successfully recover ancient DNA from the male individual’s remains as materials released during the eruption may have protected the DNA from damage.

Writing in Scientific Reports, Gabriele Scorrano at the University of Copenhagen, and colleagues, said: “To our knowledge, our results represent the first successfully sequenced Pompeian human genome.”

They add: “Our initial findings provide a foundation to promote an intensive and extensive paleogenetic analysis in order to reconstruct the genetic history of population from Pompeii, a unique archaeological site.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks