Pollen helps Covid spread further and faster, scientists find

People should avoid gatherings close to types of plants or trees known to be very active in during pollination season, study’s author says

Tree pollen may help airborne Covid particles spread further and faster, rendering the two-metre rule less effective even in outdoor settings, scientists have said.

Virus particles which are suspended in the air following an infected person’s cough or sneeze can become attached to pollen, which is dispersed in the breeze.

When someone inhales those pollen grains with the virus attached to the surface, there is a risk of airborne virus transmission, especially in crowded environments.

Specifically, the study found that the presence of pollen significantly affected the virus load carried in the air and increased the risk of infection.

Each pollen grain can carry hundreds of virus particles and on a high pollen day trees alone can release 1,500 grains per cubic metre into the air.

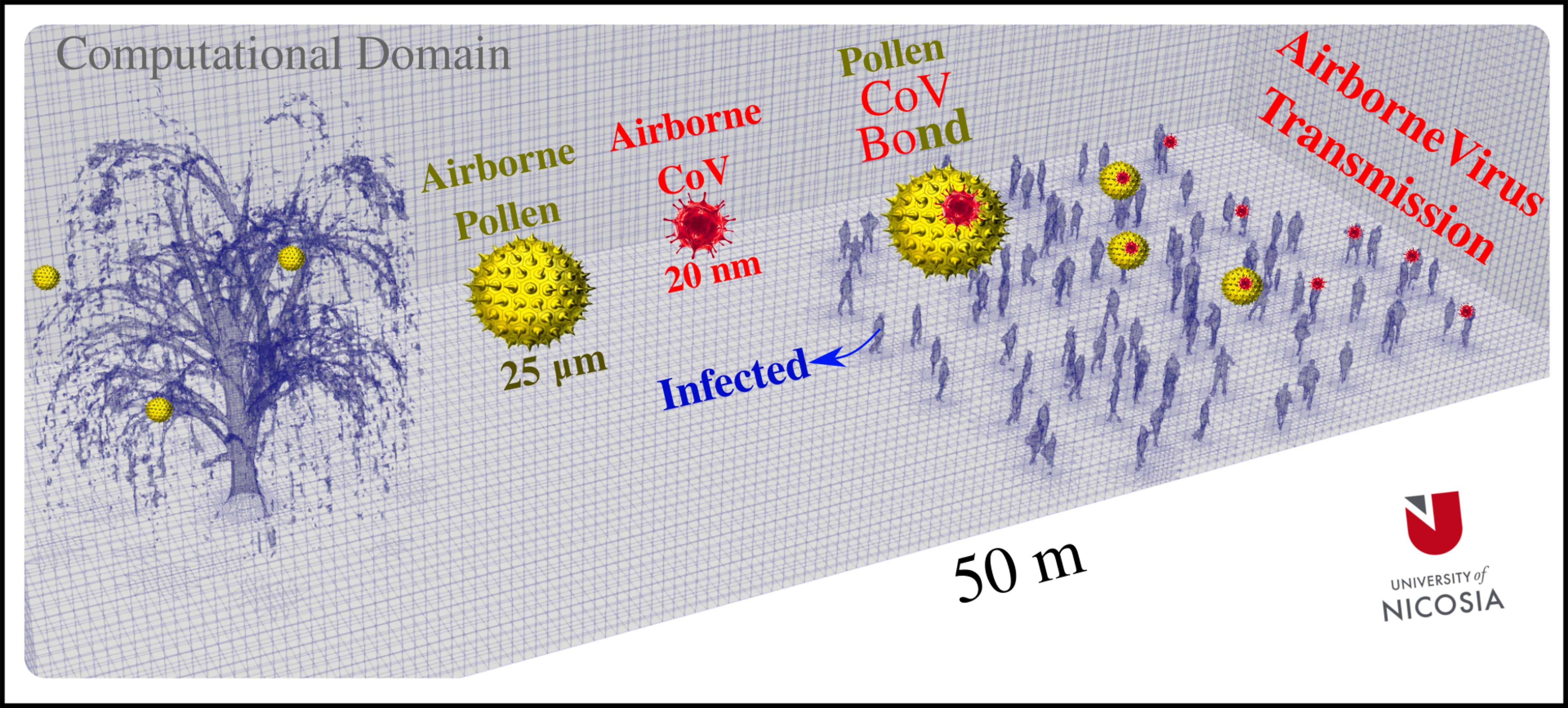

The study, led by Talib Dbouk and Dimitris Drikakis from the University of Nicosia in Cyprus, found a correlation between coronavirus infection rates and mapping of pollen concentrations.

The authors used computer modelling to mimic the pollen movement from a willow tree, with simulations of a typical spring day showing tree pollen carrying Covid blowing for 50 metres and passing through a simulated crowd of up to 100 people in less than a minute.

But they warned that pollen grains can be blown much further than that, and suggested people avoid gatherings close to plants or trees known to be very active during the pollination season.

“Pollen grains have porous and rough surfaces, which are larger than a Covid particle. During the pollination season, the pollen grains occupy essential concentrations in the atmosphere, and they are transported with the wind,“ Mr Drikakis told The Independent.

“In the presence of a crowd that might include infected individuals, the Covid particles expelled can attach to the surface of the pollen grains. The latter becomes another airborne carrier of Covid in addition to saliva droplets. When people inhale pollen grains with the virus attached to their surfaces, there is a risk of airborne virus transmission.

“To our knowledge, this is the first time we show through modelling and simulation how airborne pollen micrograins are transported in a light breeze, contributing to airborne virus transmission in crowds outdoors.”

The authors said the impact of pollen on the spread of Covid suggested the six-foot or two-metre social distancing rule in place in many countries around the world, including the UK, may not be adequate.

New guidelines informed by local pollen levels should be introduced instead to better manage the risk of Covid infection, they argued.

“Pollen grains are tiny in size and they can be easily transported with the wind for long distances - tens of kilometres away from their initial source,” said Mr Drikakis.

“Pollen grains can travel longer distances than saliva droplets. They cannot evaporate entirely, unlike the liquid saliva droplets. So, airborne pollen grains can spread the virus in the air at higher rates compared to airborne saliva droplets.

“People should avoid crowd gatherings close to some types of plants or trees known to be very active in pollen grains release during a pollination season.

“The public should be aware of the airborne transmission risks from saliva droplets indoors and outdoors and the risks arising from airborne pollen grains outdoors.”

The research, published on Tuesday in the journal Physics of Fluids, comes as the Met Office warned hay fever sufferers about a spike in pollen counts across the UK in the coming days.

Grass pollen is now in its peak season and parts of the country are set to experience very high levels over the next week.

The Met Office’s daily pollen forecast shows pollen levels in London, the Midlands, the North East and North West, as well as the South East and South West, levels will be “very high” between Tuesday and Thursday.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks