New form of photosynthesis could help scientists find alien life

Discovery could rewrite textbooks and allow for far more efficient crops

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have found a new kind of photosynthesis that could have huge consequences for life on Earth and beyond.

The new discovery could help find alien life, rewrite textbooks and lead to the development of new and more efficient crops, according to the researchers behind it. It changes our understanding of how photosynthesis works and could suggest that plants can live in ways we had never thought before.

Most life on Earth visible red light in photosynthesis, the process that underlies life on Earth. But the new discovery uses uses near-infrared light instead – and scientists have been able to recreate it themselves.

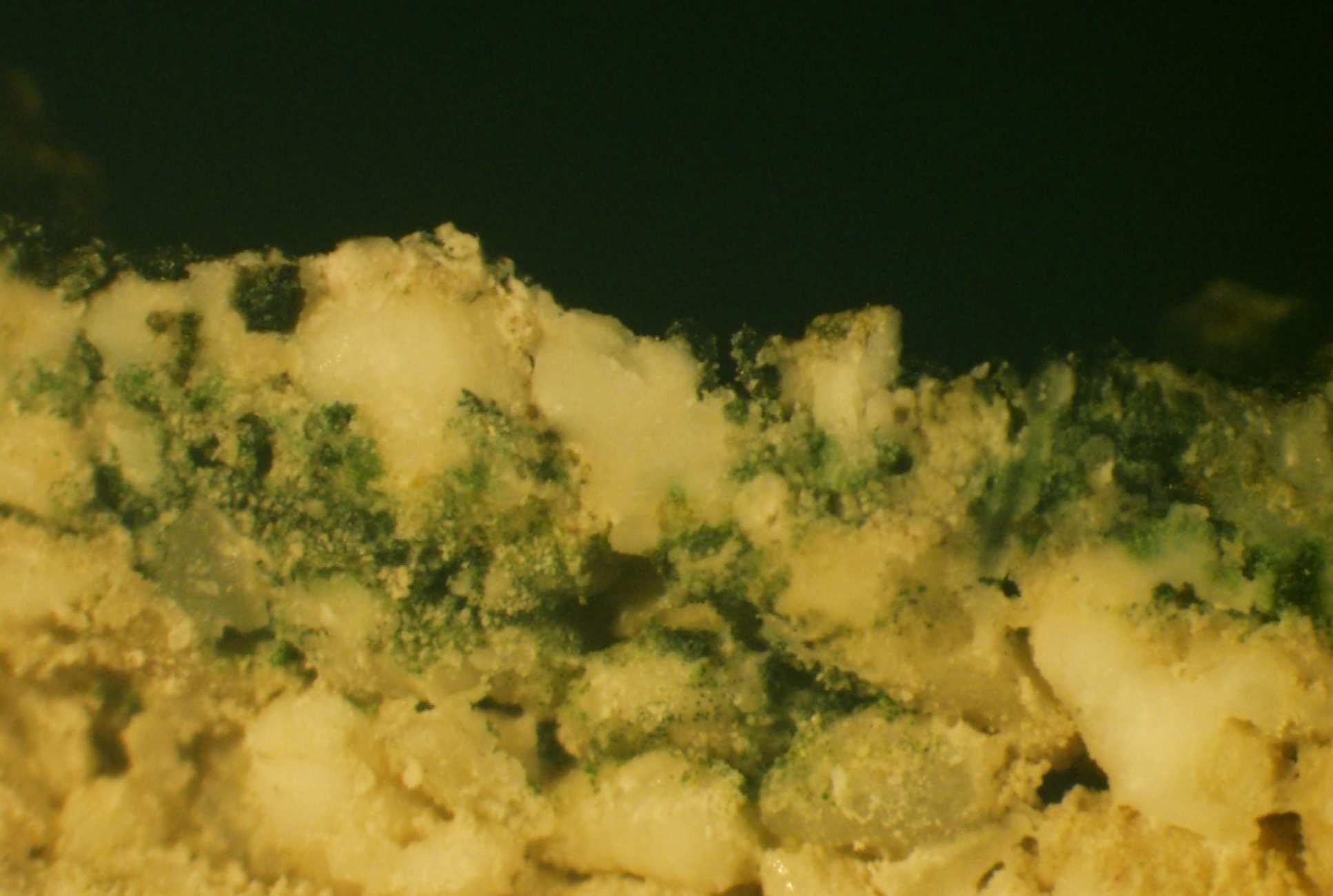

The was first found in a host of algae discovered in shaded conditions like bacterial mats in Yellowstone and in beach rock in Australia. Scientists from Imperial College London have now been able to create it in an experiment.

It has significant consequences for our estimate of whether life could be present on other planets. It might change the way we calculate whether complex life could have evolved on planets.

The normal form of photosynthesis – which children learn about in textbooks – uses the green pigment, chlorophyll-a to collect light and then use it to make useful biochemicals and oxygen required for life. The way that pigment absorbs light means that plants can only take it form the red part of the spectrum.

That means that the amount of red light was considered to be a maximum limit for how much energy could be harvested by a plant. The new discovery suggests there are other kinds of light that can be used by plants – meaning, for instance, that plants on planets lacking in red light could be able to gather energy all the same.

"The new form of photosynthesis made us rethink what we thought was possible," said Lead researcher Professor Bill Rutherford, from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial. "It also changes how we understand the key events at the heart of standard photosynthesis. This is textbook changing stuff."

Scientists already knew about one kind of bacteria that was able to do photosynthesis with light outside the visible red limit. But it was a very specific case, of a species that lives in a particular habitat: the bacteria lives under a sea-squirt that blocks out all light apart from the near-infrared.

But the new finding shows that other kinds of photosynthesis could in fact be prevalent.

“Finding a type of photosynthesis that works beyond the red limit changes our understanding of the energy requirements of photosynthesis," said Co-author Dr Andrea Fantuzzi, from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial. "This provides insights into light energy use and into mechanisms that protect the systems against damage by light.”

Scientists now hope to use the discovery to illuminate a range of different work. That could include taking the newly-discovered form of photosynthesis and helping other crops to take light from a wider range, allowing them to grow more efficiently.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments