Periodic table gets four new elements, making science textbooks around the world out of date

The new elements are still to be named — so it’s probably not worth updating any textbooks just yet

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The periodic table has been given four new elements, changing one of science’s most fundamental pieces of knowledge.

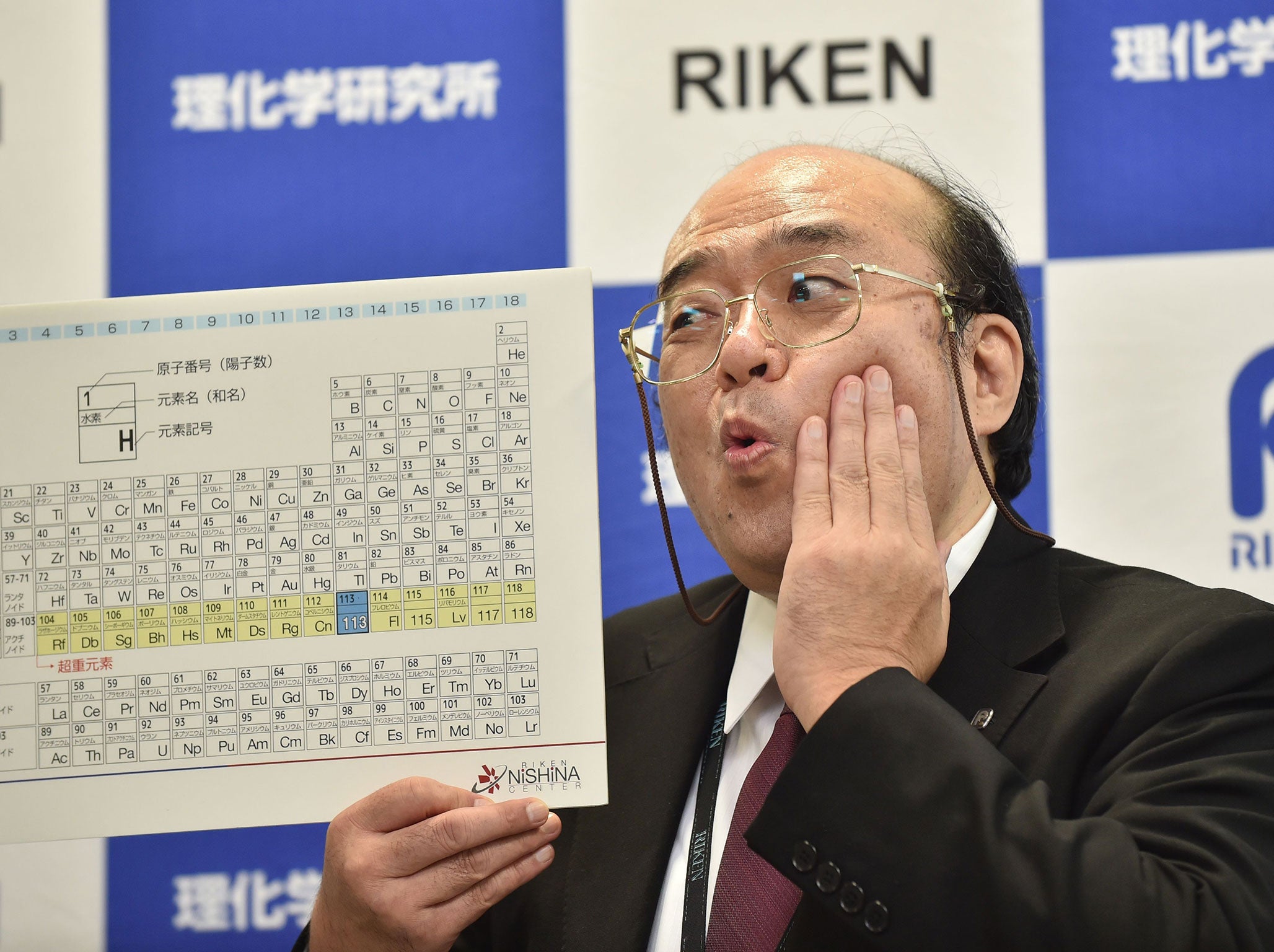

Elements 113, 115, 117 and 118 will now be added to the table’s seventh row and make it complete, after they were verified by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry on 30 December. But they are yet to receive their final names or symbols.

The new elements were discovered by team from Japan, Russia and the USA, who will all get to name their own new elements.

All of the four new admissions are man-made. The super-heavy elements are created by shoving lighter nuclei into each other and are found in the radioactive decay — which only exists for a tiny fraction of a second before they decay into other elements.

The elements have been worked on since at least 2004, when studies began showing the discovery and priority of element 113. But they have all now satisfied the strict tests to be admitted to the periodic table.

Ryoji Noyori — the former president of Riken, the Japanese institute that helped discover element 113 — said that for scientists to have the achievement recognised “is of greater value than an Olympic gold medal”.

The new elements are the first to be added since 2011, when the table got elements 114 and 116.

The new discoveries fill in the seventh row, or “period”, of the table. Because of the way that the periodic table is put together, the existence and even properties of those elements that would fill in some parts of the table can be guessed at before they are actually added.

All of the elements are yet to be given permanent names. The teams that discovered will be asked to decide what they are called, as well as to choose the one-, two- or three-letter symbol that they will be referred to on the period table.

The elements have to be named after a mythological concept, a mineral, a place or country, a property or a scientist.

For the moment, the elements are named after their number: element 113 is called ununtrium (which means 113-ium), and has the symbol Uut. Element 115 is referred to as ununpentium or Uup; 117 is called ununseptium or Uus; and 118 is called ununoctium or Uuo.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments