Ancient pee stains help pinpoint humans' switch from hunters to herders, study shows

'This is the first time, to our knowledge, that people have picked up on salts in archaeological materials and used them in a way to look at the development of animal management'

Early human settlers relieving themselves more than 10,000 years ago probably did not think their pee stains would make a splash for the ages, but they may have done exactly that.

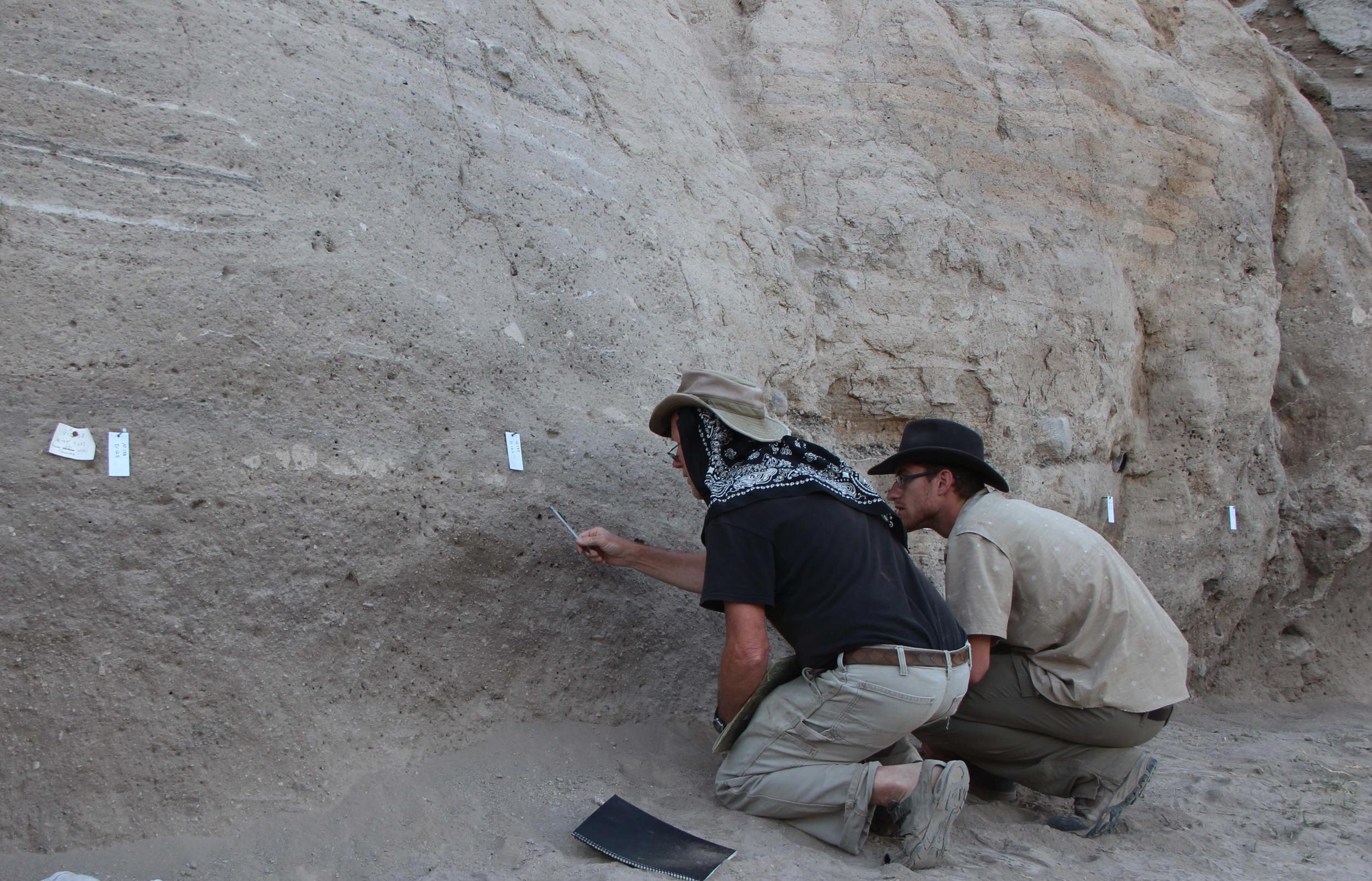

Archaeologists have begun using the salty residue of Neolithic urine to understand exactly when humanity switched from being primarily hunters to herding animals and living together in larger settlements.

Samples from the Aşıklı Höyük settlement in Turkey show how the population exploded around 10,000 years ago.

"We thought, well, humans and animals pee, and when they pee, they release a bunch of salt " said Jordan Abell, first author of the study published in Science Advances. “At a dry place like this, we didn't think salts would be washed away and redistributed."

The graduate student from America's prestigious Columbia University, added: "This is the first time, to our knowledge, that people have picked up on salts in archaeological materials, and used them in a way to look at the development of animal management."

The earliest evidence of human habitation at the sites dates back to around 10,400 years ago, but the urine salts in the soil remained relatively scarce in this period.

However samples taken around the “Neolithic revolution” between 10,000-9,700 years ago, show the level of urine salts in the soil were around 1,000 times higher.

Previous archaeological finds at the site have suggested sheep and goat domestication began around 8,450 BC and developed over the next 1,000 years until settlers were dependent on their flocks.

The new findings suggest this transition could have been much more rapid.

While they cannot distinguish between animal and human urine at present, they were able to estimate the site contained 1,790 people or animals.

This is the equivalent of going from a handful of settlers to one animal or human for every 10 square metres, roughly half the density of modern day, semi-intensive farming pens.

Combined with evidence from buildings they are able to predict the rough human population and better understand the size of herds.

This also helps to show that herding wasn’t entirely spread out from societies in the so-called “fertile crescent” around modern day Iraq, Syria, Egypt and Israel, but actually may have occurred at a number of sites independent.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks