Parrots spotted using their beaks to swing across branches like monkeys for first time

Researchers find this movement technique seen in the rosy-faced lovebird uses same forces as seen in forearms of primates

Scientists have documented for the first time parrots using their beaks to swing across the underside of branches like monkeys move from tree to tree.

Using high-speed video analysis, researchers found that this movement technique – dubbed “beakiation” – seen in the rosy-faced lovebird uses same forces as seen in the forearms of primates as they swing across branches.

The findings, published in the Royal Society Open Science journal on Wednesday, reveals the extraordinary flexibility of birds and the versatility of their beak use.

“We report that the parrot beak experiences comparable force magnitudes to the forelimbs of brachiating primates,” scientists wrote.

The unique technique in parrots also exhibits “longer-than-expected” pendular movement, similar to the swinging method used by gibbons, but in a slower and more careful nature, they say.

In the research, scientists set up a small tree-like model set up in the lab with components that can measure the force exerted on the surfaces.

The birds were then aclimatised to the experimental set-up and made comfortable to move along it length as they were recorded using two high-speed cameras.

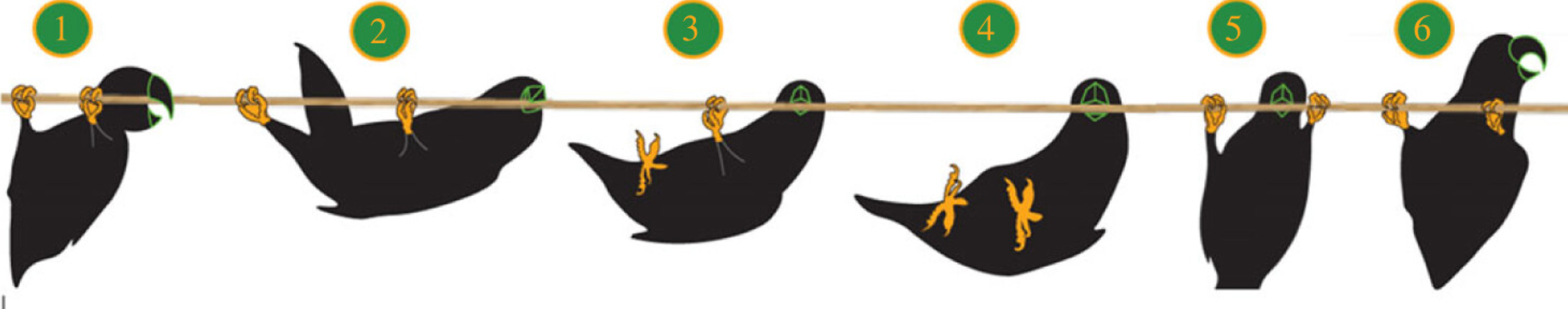

Researchers found that the birds adopted a unique alternative movement pattern in which they would first grab the support above them with their beak, before releasing both their hindlimbs “near synchronously”, such that they pivoted about the beak to swing forward.

“The hindlimbs then re-engage the substrate at a new position, and the beak assumes a new grasping position in front of the hindlimbs,” they said.

The slow and careful movement happened at about 0.1 m/s with each stride taking the bird forward by a length of 70mm, according to the study.

“We demonstrate that parrots employ a distinct form of locomotion we coin beakiation, in which the beak initially secures a grip on the support followed by the simultaneous release of both hindlimbs,” researchers explained.

Parrot beaks are known to generate large forces, sometimes even at 37 times their body weight.

The latest study also brings into view the ability of parrots’ neck muscles to generate and withstand high forces, providing the birds safety as they swing across branches with ease.

This previously undocumented movement method expands the range of movement methods observed in birds, including flying, hopping, and gliding.

While researchers acknowledge that the analysis was conducted in a lab setup, and not in the bird’s natural habitat, they say the behaviour may used in specific contexts in the wild.

The findings also underscore the difficulties in using the body anatomy of current and extinct species to predict their movement repertoire.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks