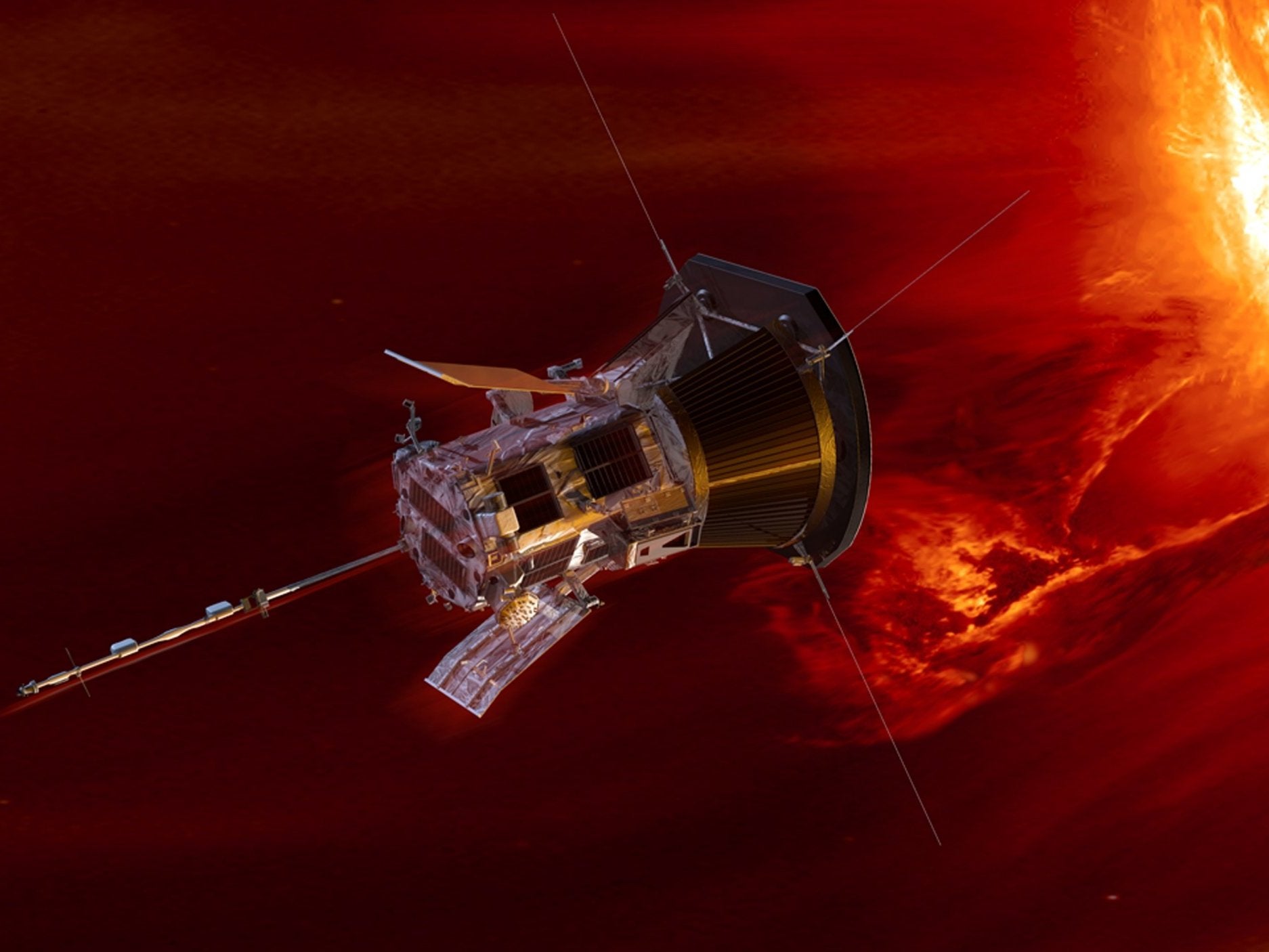

Stargazing September: The Parker probe hurtles towards the Sun

When it reaches its destination, the Parker Solar Probe will be the fastest moving manmade object ever. Back on Earth, two planets hold the fort for those watching the night skies

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was a cliffhanger. On Saturday 11 August, Nasa’s mighty Delta 4 heavy launch vehicle – second only to Elon Musk’s huge Falcon Heavy – was due to loft an iconic space probe towards the Sun. Countdown proceeded. All systems looked good. And then – gasp! At 1 min 55 secs before liftoff, the launch was aborted. There had been a problem with the rocket’s helium systems.

The next day, the team tried again. Seeing the Delta 4 blast off into the dark skies of an early Cape Canaveral morning was a huge relief. We watched as the massive solid rocket boosters dropped into the Atlantic, and breathed several sighs of relief. The Parker Solar Probe – the rocket’s payload – was on its way to the Sun.

No one could have been more relieved than Eugene Parker, a 91-year-old American solar physicist. He is the only person alive to have had a spacecraft named after him. And – amazingly – this was the first space launch he had ever been to.

Parker was ahead of his time in the 1950s, when he proposed that the Sun has weather. And, in particular, the solar wind: a stream of energised protons and electrons boiling off our local star at speeds of up to a million miles per hour.

Not everyone believed him. But he was right. How right! The solar wind can be a ferocious beast, especially when the Sun winds itself up into maximum magnetic activity (which occurs roughly every 11 years). Then sunspots pepper the Sun’s surface. These are places where our Sun’s churning magnetic field breaks through, and causes all kinds of electromagnetic chaos when their field lines intercept, making a star-powered short circuit. Exploding solar flares hurl powerful charged particles into the solar system. In the Sun’s outer atmosphere – the corona – vast clouds of gas called coronal mass ejections erupt into space, posing an even more dangerous threat.

The impact on Earth? The first is beautiful and benign: we get to see the aurorae. These stunning, shifting rays and curtains of light, visible at high northern and southern latitudes, are caused by the attraction of magnetism: the Sun’s charged particles heading for our magnetic poles.

But it’s not all good news. The effects of the Sun’s unpredictable weather are crucial when it comes to Earth-orbiting satellites. It can knock out their electronics. And when you think how much we depend on weather and communications satellites, it’s vital that we have warning. And with human spaceflight – and space tourism – destined to expand, it’s essential to protect future astronauts from the risk of radiation.

Even on the ground, we’re not safe. Extreme solar activity can disrupt power lines and communications links. On one occasion, it knocked out the Quebec Stock Exchange. Now, there’s a disaster!

As we write, the Parker probe is on its way to Venus, where it will use the planet’s gravity to shrink its orbit. It will have its first encounter with the Sun on 1 November (carrying a memory card of a million wellwishers who support the mission).

Over the next seven years, Parker will make repeated dips into the Sun’s corona. At its closest, it will be just 3.4 million miles from the Sun’s surface (for comparison, Earth is 93 million miles away). And it will be heated to 1,400C. To protect its sensitive instruments, the hardy space probe has a carbon heat shield – 4.5 inches thick – which took 10 years to develop. When it circles the Sun, it’ll be the fastest manmade object ever, travelling at 430,000mph.

What do we hope to learn from the Parker probe? First, why is the corona so hot? Compared to the Sun’s surface (5,500C), it seethes at a million degrees. And what causes flares and coronal mass ejections? How can we get advance warning and protect ourselves from them?

In the end, the Parker probe is an audacious and visionary project. What a way to get up close and personal to our local star.

What’s up?

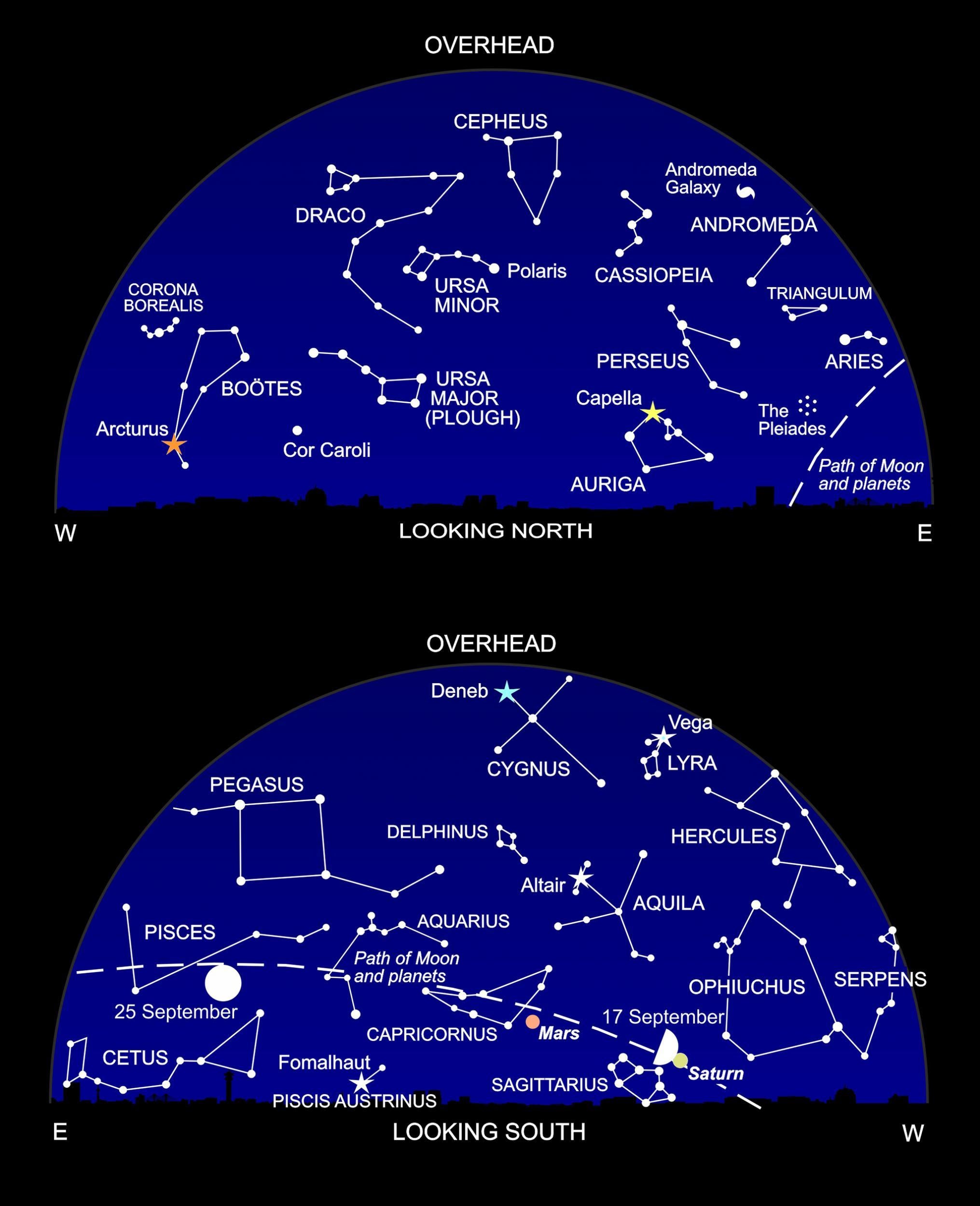

We’re losing our Evening Star this month: brilliant Venus has been blazing in low in the west after sunset for the past six months, but by the end of September it will sink into the twilight glow. To its left, giant Jupiter is also sinking down to the southwestern horizon, and setting about 9pm.

To the south, though, two bright planets are still holding the fort. The bright reddish “star” is Mars, gradually fading as the fast-moving Earth pulls away from the red planet. To its right, creamy yellow Saturn lies low among the faint stars of Sagittarius. The ringworld lies right next to the first quarter moon on 17 September.

The most distant planet, Neptune, is closest to Earth on 7 September, lying in the constellation Aquarius. But “closest” still means a whacking 2.7 billion miles (4.3 billion kilometres), and you’ll need binoculars or a small telescope to spot it at all.

Also at the beginning of the month, if you’re an early bird you may spot the closest planet to the Sun, tiny Mercury, low in the east around 5am.

We also have a comet around at the moment, although again – frustratingly – it’s just too dim to be seen with the naked eye. But “sweep” the sky below the bright star Capella with good binoculars to try and spot the fuzzy patch that is comet Giacobini-Zinner. This celestial visitor swoops around the solar system every 6.6 years, and it’s closest to Earth on 10 September. Hold on till December for a comet that you just can’t miss.

Diary

6 September, morning: Mercury very near Regulus

7 September: Neptune at opposition

9 September, 7.01pm: New moon

10 September: Comet Giacobini-Zinner nearest to Earth

12 September: Crescent moon near Venus

13 September: Crescent moon near Jupiter

15 September: Crescent moon near Antares

17 September, 0.15am: Moon at first quarter, near Saturn

19 September: Moon near Mars

23 September, 2.54am: Autumn Equinox

25 September, 3.53am: Full moon; Mercury at greatest western elongation

29 September: Moon occults the Hyades

For the lowdown on all that’s up in the sky next year, check out Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest’s newly published book, ‘Philip’s 2019 Stargazing'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments