Paralysed monkeys walk again after scientists fit 'brain-spine interface'

'For the first time, I can imagine a completely paralysed patient able to move their legs through this brain-spine interface'

Swiss scientists have helped monkeys with spinal cord injuries regain control of non-functioning limbs in research which might one day lead to paralysed people being able to walk again.

The scientists, who treated the monkeys with a neuroprosthetic interface that acted as a wireless bridge between the brain and spine, say they have started small feasibility studies in humans to trial some components.

"The link between the decoding of the brain and the stimulation of the spinal cord – to make this communication exist – is completely new," said Jocelyne Bloch, a neurosurgeon at the Lausanne University Hospital who surgically placed the brain and spinal cord implants in the monkeys.

"For the first time, I can imagine a completely paralysed patient able to move their legs through this brain-spine interface."

Professor Gregoire Courtine, a neuroscientist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (EPFL) which led the work, cautioned there were major challenges ahead and "it may take several years before this intervention can become a therapy for humans".

Publishing their results in the journal Nature on Wednesday, the team said the interface works by decoding brain activity linked to walking movements and relaying that to the spinal cord below the injury through electrodes that stimulate neural pathways and activate leg muscles.

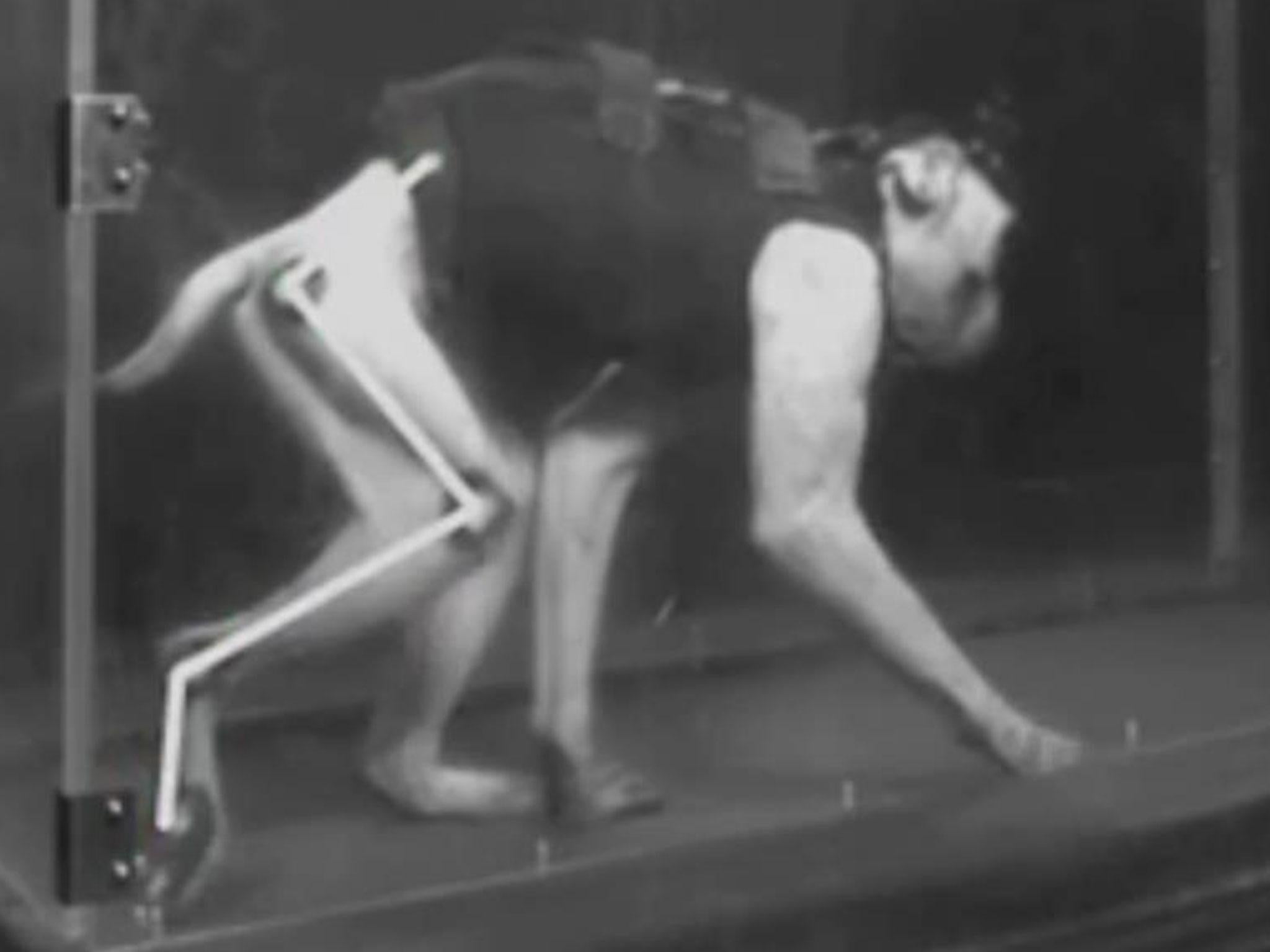

In bypassing the injury and restoring communication between the brain and the relevant part of the spinal cord, the scientists successful treated two rhesus monkeys each with one leg paralysed by a partial spinal cord lesion.

One of the monkeys regained some use of its paralysed leg within the first week after injury, without training, both on a treadmill and on the ground, while the other took around two weeks to recover to the same point.

"We developed an implantable, wireless system that operates in real-time and enabled a primate to behave freely, without the constraint of tethered electronics," said Professor Courtine.

"We understood how to extract brain signals that encode flexion and extension movements of the leg with a mathematical algorithm. We then linked the decoded signals to the stimulation of specific hotspots in the spinal cord that induced the walking movement."

The brain and spinal cord can adapt and recover from small injuries, but until now that ability has been far too limited to overcome severe damage.

Other attempts to repair spinal cords have focused on stem cell therapy and on combinations of electrical and chemical stimulation of the cord.

Independent experts not directly involved in this work said it was an important step towards a potential future where paralysed people may be able to walk again.

Simone Di Giovanni, a specialist in restorative neuroscience at Imperial College London, said EPFL's results were "solid, very promising and exciting" but would need to be tested further in more animals and in larger numbers.

"In principle this is reproducible in human patients," he said. "The issue will be how much this approach will contribute to functional recovery that impacts on the quality of life. This is still very uncertain."

Reuters

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks