One step closer: the pill that brings jet lag down to earth

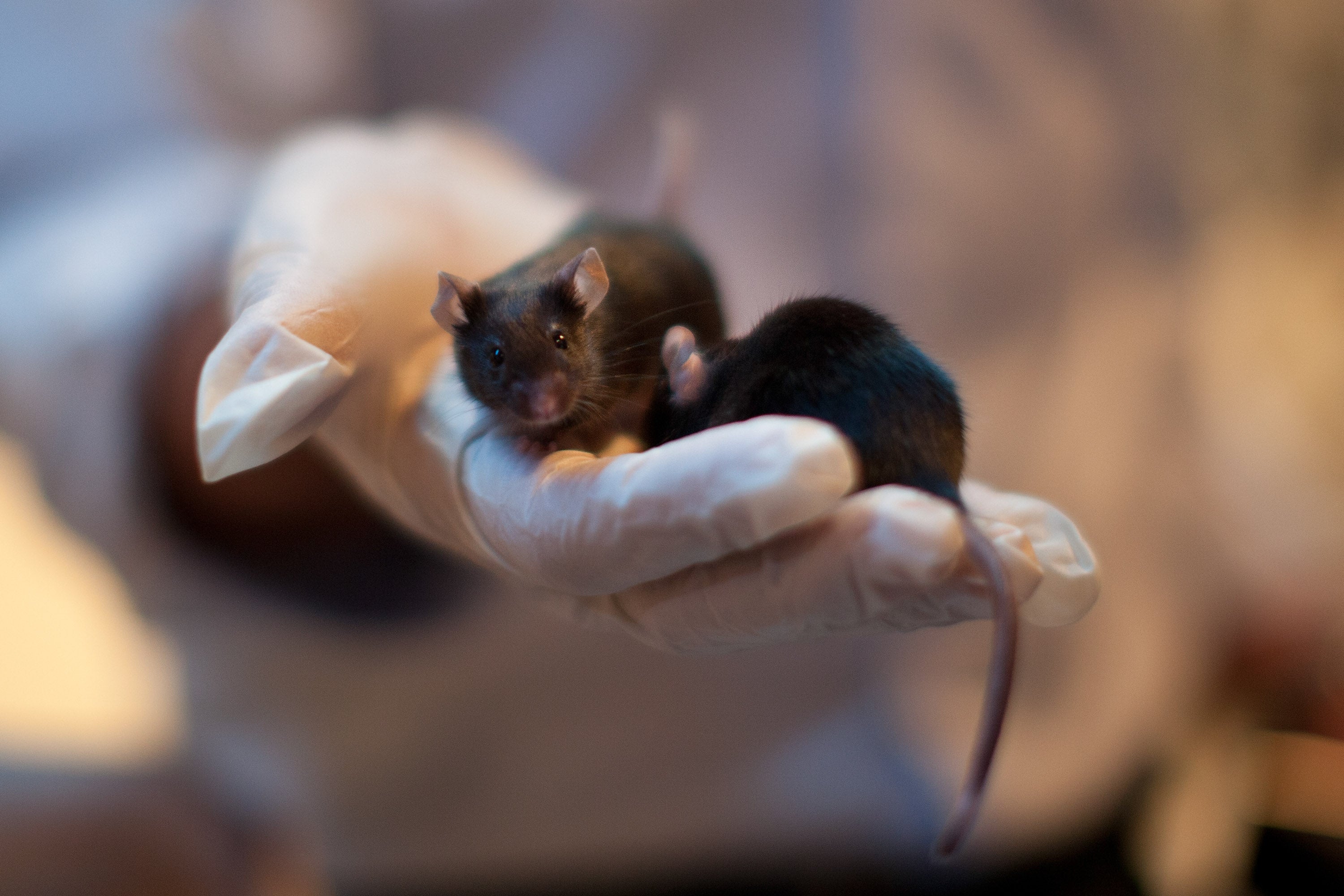

Scientists blocked particular gene to improve the recovery time of mice

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have moved a step closer to creating a specialist pill for jet lag, after research in mice revealed a possible mechanism for speeding up the body's natural response to moving across time zones.

Researchers at the University of Oxford found they could improve the recovery time of mice exposed to irregular patterns of light and dark by blocking a particular gene in the brain, responsible for regulating the body's internal clock.

Nearly all living things have an internal, subcellular mechanism - known as the circadian clock - that synchronises a variety of bodily functions to the 24-hour rhythm of the Earth's rotation. The circadian clock is regulated by a number of stimuli - chief among them light detected by the eye.

But when daily patterns of light and dark are disrupted - as when we travel across several time-zones - the body clock falls out of synch, resulting in several days of fatigue and discomfort as our cells adjust to new daily patterns - experienced by long-haul fliers as jet lag. The body takes about one day to adjust for every time zone crossed.

To understand the effect this has on the brain, researchers at the University of Oxford exposed mice to irregular patterns of light and dark to simulate moving across time zones.

They monitored the activity of genes in the part of the brain responsible for setting the circadian clock - the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) and observed that hundreds of genes were activated by light detected from the eye, all of which helped the body adjust to a new day-night rhythm.

However, one particular molecule, called SIK1, was found to have the opposite effect when activated by light - deactivating the body's response to light adjustments and therefore slowing down it's adjustment to a new time zone.

By injecting a small interfering RNA - a tiny strand of genetic material that can interfere with the function of a gene - scientists were able to block the action of the SIK1 molecule, meaning that the mice were able to adjust their body clocks far more quickly. A simulated time zone difference that had taken five or six days to adjust to, now took just one or two days.

"We've identified a system that actively prevents the body clock from re-adjusting," said Dr Stuart Peirson, the study team leader and a senior research scientist at Oxford's Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences. "If you think about, it makes sense to have a buffering mechanism in place to provide some stability to the clock… But it is this same buffering mechanism that slows down our ability to adjust to a new time zone and causes jet lag."

He told The Independent that although a pill for jet lag was several years away, the study provided a possible route for development.

"A small interfering RNA is a neat molecular way of being able to turn off one gene within cells," he said. "There's no reason you couldn't develop specific drugs to inhibit this particular mechanism, so it should be possible in the future to develop drugs that allow us to adjust more quickly and help alleviate jet lag."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments