How animals' eating habits are not what they seem: from plant-munching sharks to blood-guzzling parrots

Nature seems to have a habit of surprising us. Or perhaps it’s just that we forget that animals don’t read the books we write about them

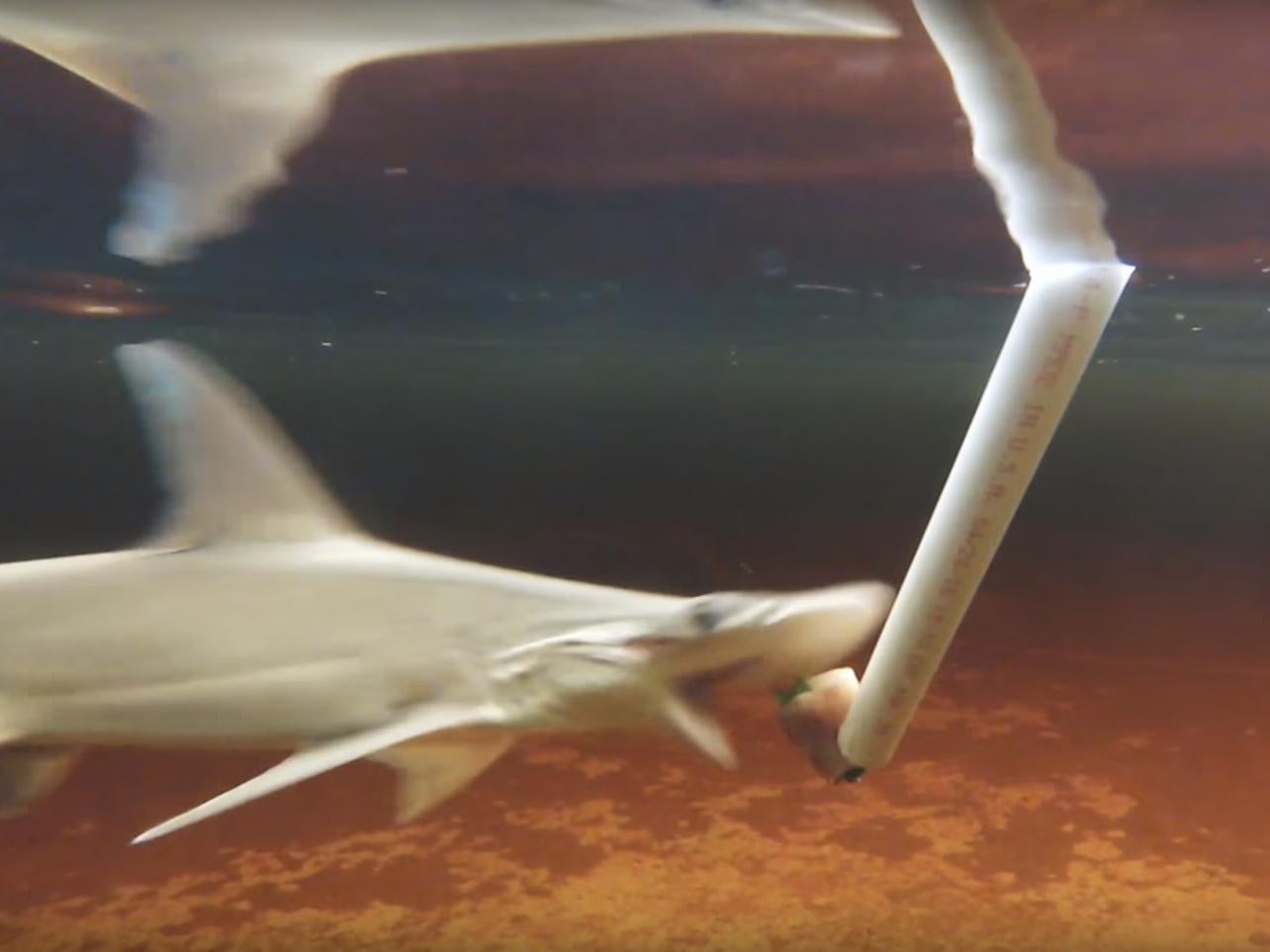

Animals don’t always stick to traditional menus, and they certainly don’t read the descriptions of their diets we include in textbooks. When it recently emerged that a notorious carnivore (a shark) was actually selecting the vegetarian option, scientists were intrigued.

We’ve known for some time that bonnethead sharks consume large quantities of seagrass, but this was thought to be accidental – pesky vegetation finding its way into their mouths while they were hunting crabs. Yet this new research has revealed that the bonnethead shark actually digests and draws nutrition from the seagrass – the first known omnivorous shark.

This finding isn’t just an interesting new fact about sharks, it’s an important acknowledgement that environments need to be protected for reasons we may not have even considered. Who’s to say there aren’t other examples of species interacting with their habitats in unexpected ways?

The natural world is far from fully understood, and while new scientific discoveries continue to be made, these revelations aren’t keeping pace with the rate of environmental destruction. Equally, nature seems to have a habit of surprising us. Or perhaps it’s just that we forget that animals don’t read the books we write about them.

In the field of feeding ecology alone, there are multiple examples of animals breaking the “rules” we’ve set for them. If the plant-eating shark was a shock, what about supposedly strict vegetarians turning to meat? Although carcass-eating bunnies and cannibal hippopotamuses may sound like something out of a horror movie, they aren’t restricted to the imaginations of screenwriters.

The food chain’s grislier links

Let’s take the case of the hippo first. These African animals are described in most textbooks as strict herbivores, who only use their large tusks and teeth for display and territorial fights. However, the rotund vegetarians have been seen consuming animal carcasses, including other hippos. This behaviour is not isolated to a single observation, and scientists believe it may even help diseases such as anthrax to spread more widely throughout hippo populations.

As for the cute and fluffy bunnies, even these will choose meat over veg in some circumstances. In a mixed-species zoo exhibit, the chicken and mice offered to captive birds of prey were actually consumed by domestic rabbits sharing the enclosure.

More gruesome examples of erstwhile vegetarians abound. The poor table manners of sheep and deer were reported in the late 1980s, as they were seen biting the legs, wings and heads off fledgling chicks. Only a few months ago, startling footage of rare curlew nests being raided by sheep in the UK caused a sensation on social media.

But the dining tables are turned in New Zealand, where it’s sheep who are the victims. The kea bird, New Zealand’s friendly “mountain clown”, is a native parrot with a taste for open wounds on livestock, and can often be seen plucking tissue and blood from the animals while perched on their backs.

As early as 1895, the species’ feeding habits were the subject of scientific interest. However, it was the interest of farmers in these birds that warranted the greatest concern, as the keas’ apparent thirst for blood prompted a campaign to exterminate them.

The jury may still be out as to whether keas are clowns or killers, but what does appear accurate is that they are highly adaptable opportunists who don’t play by any rules we may make for them.

A fresh look at food choices

These examples force us to rethink the notion that feeding habits are a simple reflection of gut anatomy. Perhaps feeding behaviour and strategies are driven more by opportunity than physiology.

Rabbits, hippos and keas don’t have anatomies that make them good at capturing prey, but that doesn’t mean to say they can’t, and won’t, make use of animal tissues if they get the chance. Likewise, not all carnivores may be as hungry for meat as we once thought.

Free-living animals must make the most of the opportunities presented in their environment. If that means tucking into a chum that’s just died, or taking a flexitarian approach to one’s dietary regime, then that’s what they’ll do.

After all, as my colleague Ellen Dierenfeld points out, carnivores and herbivores are just two extreme ends of the scale, and it’s only humans that tend to think of the points on that scale as immovable. So until the animals learn to write their own textbooks, we should be prepared for the unexpected, and never take anything off the menu when it comes to understanding the natural world.

Katherine Whitehouse-Tedd is a senior lecturer at the School of Animal, Rural and Environmental Sciences at Nottingham Trent University. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks