Scientists discover world’s oldest human-built structure, built by an extinct species

The discovery is likely to change archaeologists’ understanding of the evolution of early human technology

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.British and African archaeologists have discovered evidence of the world’s oldest human-built structure, built by an extinct species of humans from half a million years ago. It was unearthed in southern Africa.

Made of worked timber, it is likely that it was built as an elevated trackway across marshland – or as a raised platform in the middle of a wetland area, perhaps as part of a hunting base or butchery facility.

It was unearthed in waterlogged ground in northern Zambia – and is at least twice as old as any other known human-made structure.

The discovery is likely to change archaeologists’ understanding of the evolution of early human technology and cognitive abilities.

The elevated timber trackway or platform was just a small part of a prehistoric human presence on the southern bank of the Kalambo River. It was found just a few hundred metres upstream from two of the world’s most spectacular natural wonders – a 235-metre high waterfall and a 300-metre deep canyon.

It is likely that the falls and the unusually varied local topography were indirectly responsible for attracting early human hunter-gatherers to the area, including the world’s first construction “engineers” and carpenters.

Immediately upstream from the falls is a large and fertile floodplain which would have featured marshland, small lakes, minor waterways and riverine woodland as well as the main river. Woodland, with other tree species, would have covered the hillslopes adjacent to the floodplain.

But immediately downstream, the river flows through an impressive three-mile-long canyon with its own localised rainforest, partly generated by the spray from the waterfall. And just three miles further on, the river flows into one of Africa’s largest lakes, Lake Tanganyika, which is particularly rich in fish and would have attracted vast herds of animals.

Each of these environments would have attracted different types of animals and would have featured different plants, fruits and nuts – all of which would, in turn, have attracted the early humans.

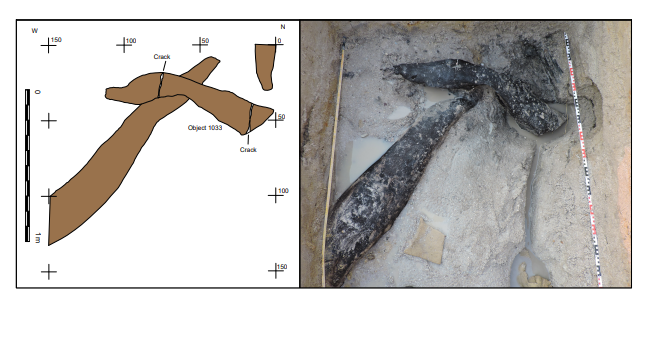

The archaeologists have so far found two parts of the timber structure – a 1.4-metre-long section of a tree trunk and a tree stump, both of which had been modified by prehistoric carpenters.

The tree trunk had been felled and then shaped so that it tapered at both ends. A 13cm U-shaped notch had then been carved into its side. It had then been placed horizontally on top of the tree stump which had itself been carved and shaped to ensure that its top 20cm could fit neatly into the horizontally carved tree trunk’s U-shaped notch.

By positioning the modified tree trunk in this way, it was effectively “locked” on top of the stump, ensuring that the trackway or platform was kept some 20cm above the marsh.

Also dating from around half a million years ago was a large wooden wedge which was found just a few metres away. It was probably used for splitting timber.

The archaeologists have also unearthed a variety of cutting, chopping and scraping tools, all made of stone, and a possible hearth for cooking.

The prehistoric humans who lived there were members of a now-extinct species known as Homo heidelbergensis – a species which had already by that time colonised most of Africa, western Asia and Europe and which flourished between 600,000 years ago and 300,000 years ago.

However, by around 300,000 years ago Heidelbergensis became extinct – possibly because of competition from newer, even more advanced human species, namely Neanderthals and ourselves (Homo sapiens).

The archaeological investigations have been carried out over the past four years by archaeologists and other scientists based in the UK, Belgium and Zambia - from the universities of Liverpool, Aberystwyth, Royal Holloway and Liège and from Zambia’s National Museums Board and the country’s National Heritage Conservation Commission.

An academic report on the project was published by the scientific journal, Nature, on Wednesday.

Project director, Professor Larry Barham, from the University of Liverpool’s Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, leads the international ‘Deep Roots of Humanity’ research project, which includes the Kalambo Falls area investigation. He said: “This find is helping to change how we think about a long-extinct species of humans.”

The specialist dating of the finds was undertaken by experts at Aberystwyth University. They used luminescence dating techniques, which reveal the last time minerals in the sand surrounding the finds were exposed to sunlight, to determine their age.

“At this great age, putting a date on finds is very challenging. Luminescence dating allows us to date much further back in time, to piece together sites that give us a glimpse into human evolution,” said Professor Geoff Duller, from Aberystwyth University.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments