New water plumes from Jupiter’s moon Europa raise hopes of detecting microbial life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

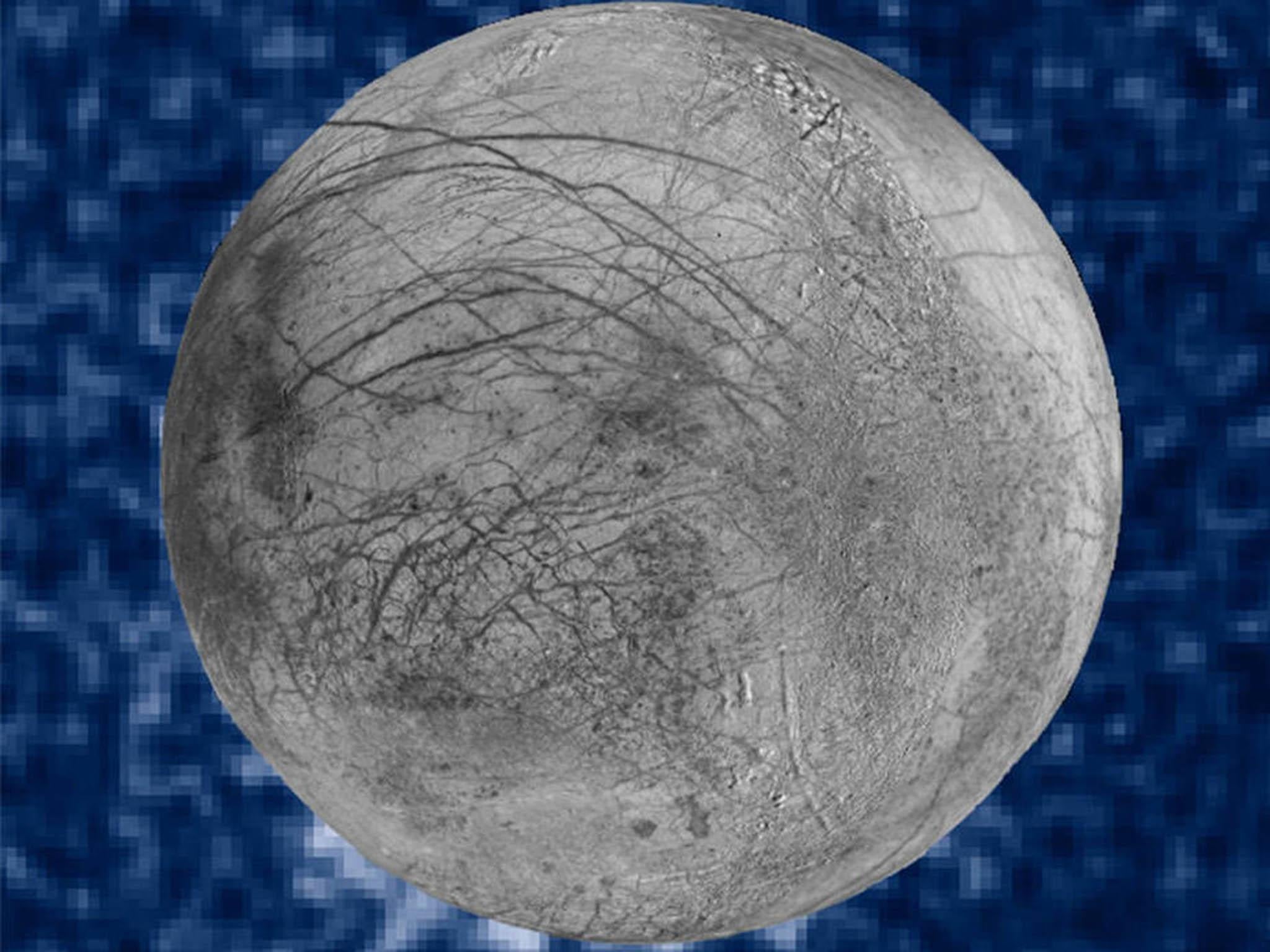

Your support makes all the difference.The Hubble Space Telescope has obtained evidence of Jupiter’s moon Europa erupting plumes of water vapour according to NASA reports. Hubble first caught a glimpse of the jets in December 2012, but now more plumes have been revealed using a different technique.

The discovery is exciting, as Europa, with its large subsurface ocean, is one of the best candidates for microbial life in the solar system – despite its surface temperature being a frigid -160°C. And plumes mean that samples of microbes could be collected during a flyby, without having to land on the surface.

Europa is Jupiter’s innermost large, icy moon (only slightly smaller than our own moon) and has about 100km of ice and liquid water surrounding its rocky interior.

Galileo discovery

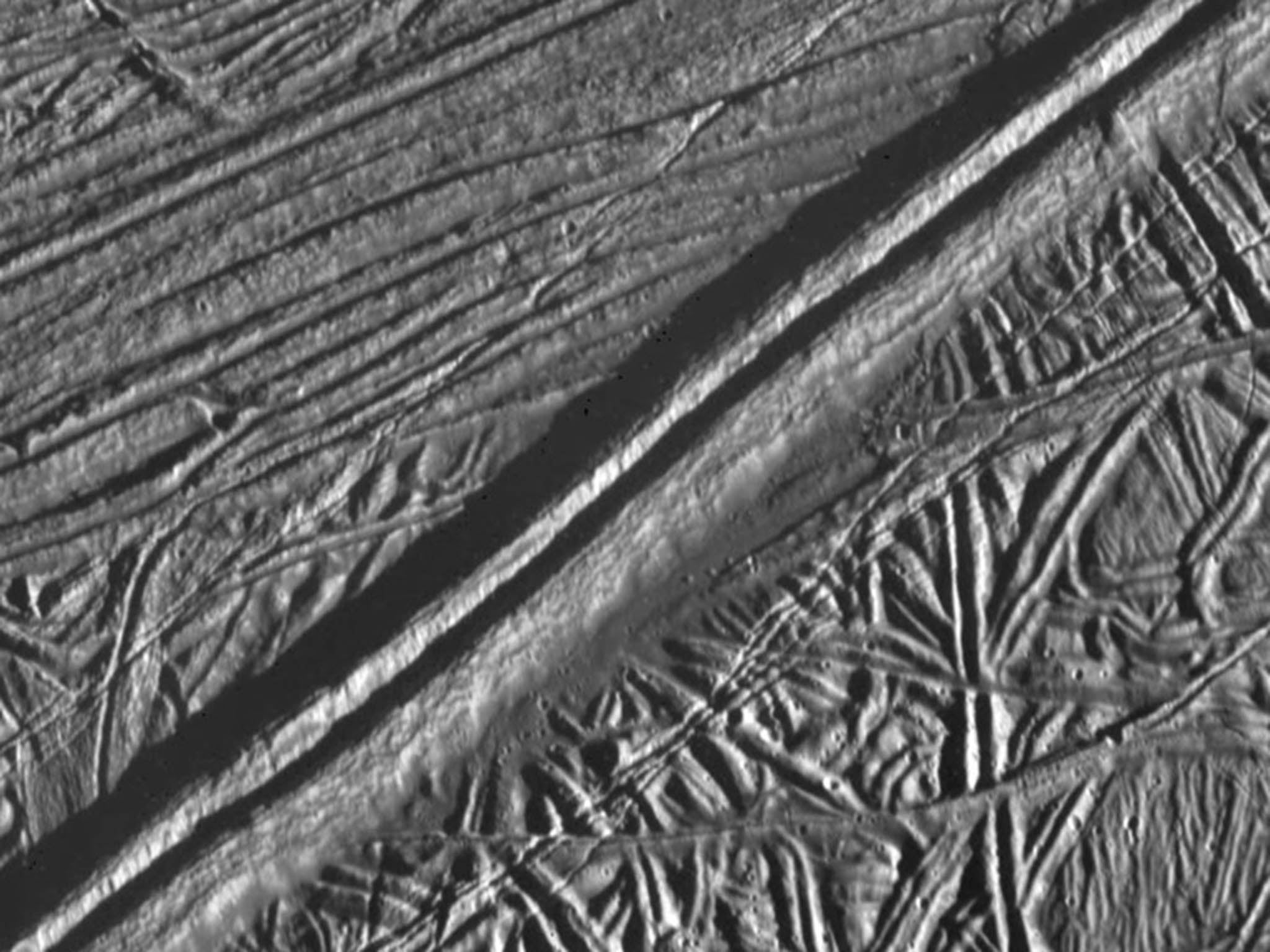

Scientists started getting really interested in Europa following observations by NASA’s Galileo probe of Jupiter and its moons from orbit between 1995 and 2003. These showed that Europa’s surface ice is marked by multiple generations of parallel ridges and grooves, except where this pattern has been shattered by the surface breaking apart into randomly disposed slabs (known as “chaos regions”). This can be explained if Europa’s icy shell floats on a layer of liquid water. Each grooved ridge could mark a crack that opened and closed with the changing tide during Europa’s 3½-day orbit of Jupiter – the ridges being formed from slush that was squeezed to the surface each time the crack closed. The chaos regions would represent slabs of the ice shell that broke apart as a region of the ocean became melted from below, powered by a release of tidal heat through the ocean floor – now frozen into a new configuration.

Microbes could live near the floor of Europa’s internal ocean, feeding off the chemical energy supplied where hot water (“hydrothermal”) vents discharge chemicals dissolved out of the tidally-heated rocky interior. This is the kind of setting where life on Earth is thought to have begun. Microbes whose ancestors had developed a taste for sunlight might now be found surviving by photosynthesis (like plants) in the water drawn up and (mostly) forced down again every time a tidal crack opened. However, although Galileo searched as hard as it was able (hampered by a failed antenna), it found no signs of present-day activity, such as water venting to space.

Europa versus Enceladus

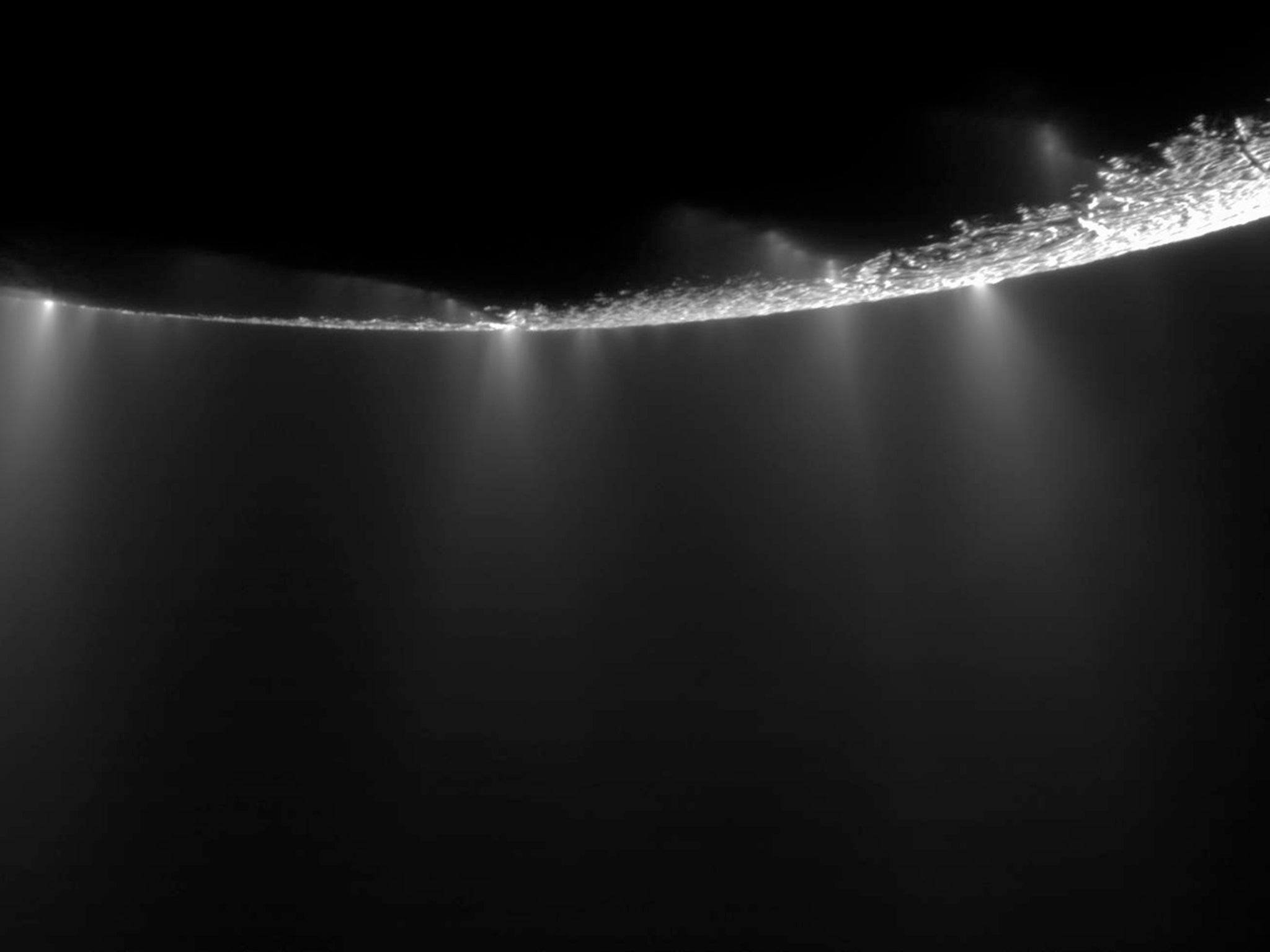

Soon after Galileo’s findings, Europa’s crown as the most active icy moon was snatched away by Enceladus, a much smaller (500km diameter) moon of Saturn, in 2005. The Cassini probe discovered jets (or plumes) of ice crystals venting to space from cracks near Enceladus’s south pole. In the decade that followed, it became clear that Enceladus has a global internal ocean between its icy surface shell and a rocky interior.

Cassini was even able to fly through the plumes, finding them to be chemically rich and bearing signs of the kind of water-rock interaction which could feed micriobial life. This raised hopes that such fly-throughs could one day find signs of microbial life (including maybe even a few ejected microbes themselves), without the need for a technically-challenging landing on the surface.

It wasn’t until December 2012 that the Hubble Space Telescope at last detected evidence for an active plume erupting from Europa, in the form of a faint ultraviolet glow caused by atoms of hydrogen and oxygen rising up to 200km above Europa’s south pole. This is probably water molecules broken apart in the harsh space environment.

However, subsequent efforts failed to find any repeat evidence, until now. The latest evidence was obtained with an enterprising new technique, using Jupiter as a light source to reveal plumes as Europa passes across its face. The Hubble Space Telescope was used to collect ultraviolet images during ten transits of Europa across Jupiter in 2014, which on three occasions revealed plumes erupting above the edge of Europa’s disc. This shows that the plumes are intermittent.

However, sometimes three or four distinct plumes can be made out, and given that the technique can see only those plumes erupting near the visible edge of the disc, there may be many more undetectable plumes in front of or behind the disc.

Hopefully it won’t be too long before a mission designed to detect microbial life from the plumes of Europa or Enceladus sets off to find out. It certainly seems like a worthwhile endeavour – especially after the emergence of this latest evidence.

David Rothery is a professor of planetary geosciences, at The Open University. This article originally appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments