Scientists discover new subatomic particle at Large Hadron Collider laboratory

Physicists hope findings will help explain a key force that binds matter together

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have found an extra charming new subatomic particle that they hope will help further explain a key force that binds matter together.

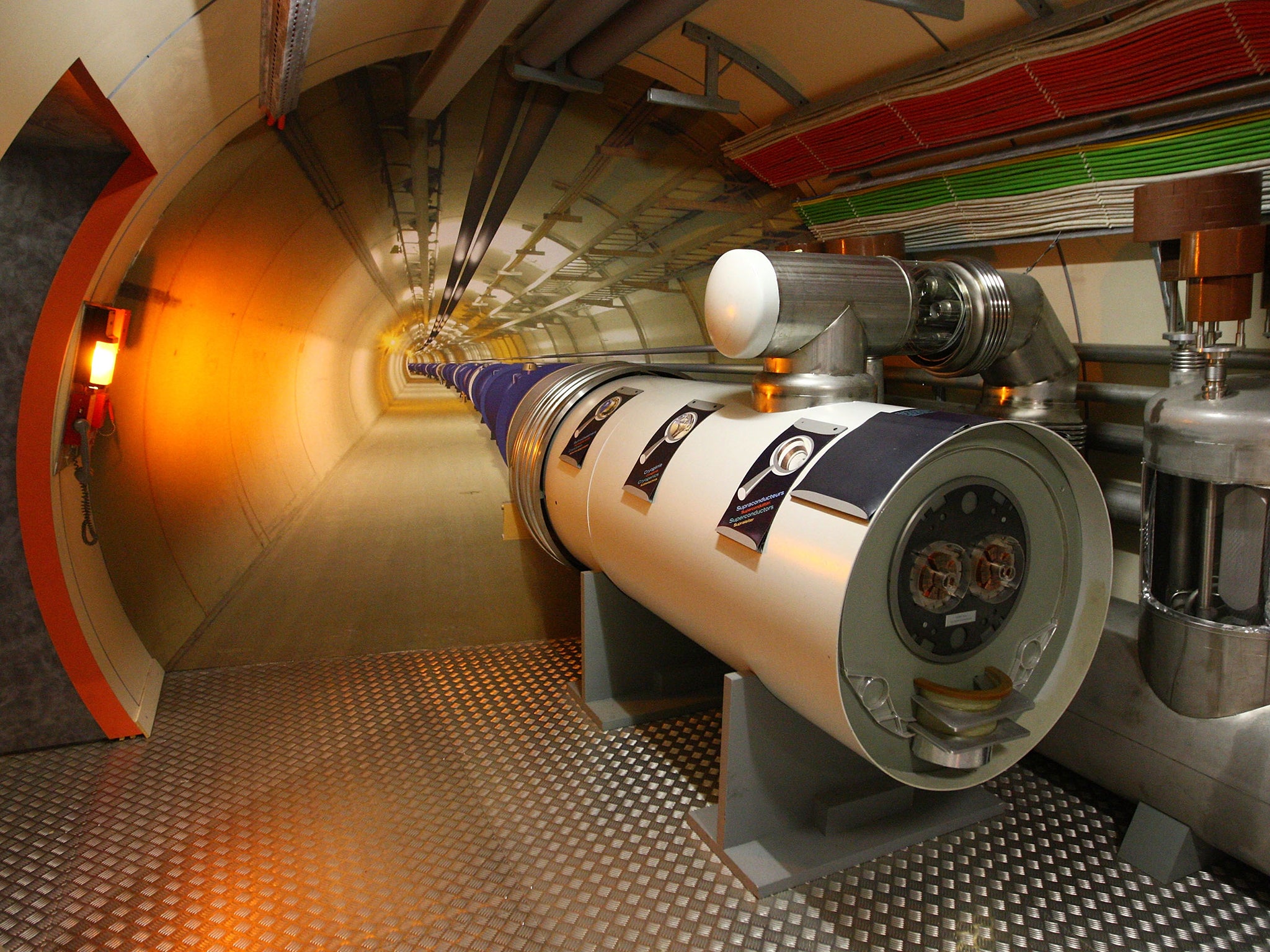

Physicists at the Large Hadron Collider in Europe announced on Thursday the fleeting discovery of a long theorised but never-before-seen type of baryon.

Baryons are subatomic particles made up of quarks. Protons and neutrons are the most common baryons. Quarks are even smaller particles that come in six types, two common types that are light and four heavier types.

The high-speed collisions at the world's biggest atom smasher created for a fraction of a second a baryon particle called Xi cc, said Oxford physicist Guy Wilkinson, who is part of the experiment.

The particle has two heavy quarks — both of a type that are called "charm"— and a light one. In the natural world, baryons have at most one heavy quark.

It may have been brief, but in particle physics it lived for "an appreciably long time," he said.

The two heavy quarks are in a dance that's just like the interaction of a star system with two suns and the third lighter quark circles the dancing pair, Mr Wilkinson said.

"People have looked for it for a long time," Mr Wilkinson said. He said this opens up a whole new "family" of baryons for physicists to find and study.

"It gives us a very unique and interesting laboratory to give us an interesting new angle on the behavior of the strong interaction (between particles), which is one of the key forces in nature," Mr Wilkinson said.

Chris Quigg, a theoretical physicist at the Fermilab near Chicago, who wasn't part of the discovery team, praised the discovery and said "it gives us a lot to think about."

The team has submitted a paper to the journal Physical Review Letters.

The Large Hadron Collider, located in a 27-kilometre (16.8-mile) tunnel beneath the Swiss-French border, was instrumental in the discovery of the Higgs boson. It was built by the European Organization for Nuclear Research, known by its French acronym CERN.

Associated Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments