Homo naledi: New species of human discovered after ancient skeletons unearthed in South Africa

Species had feet designed for long-distance walking, but also bears ape-like characteristics

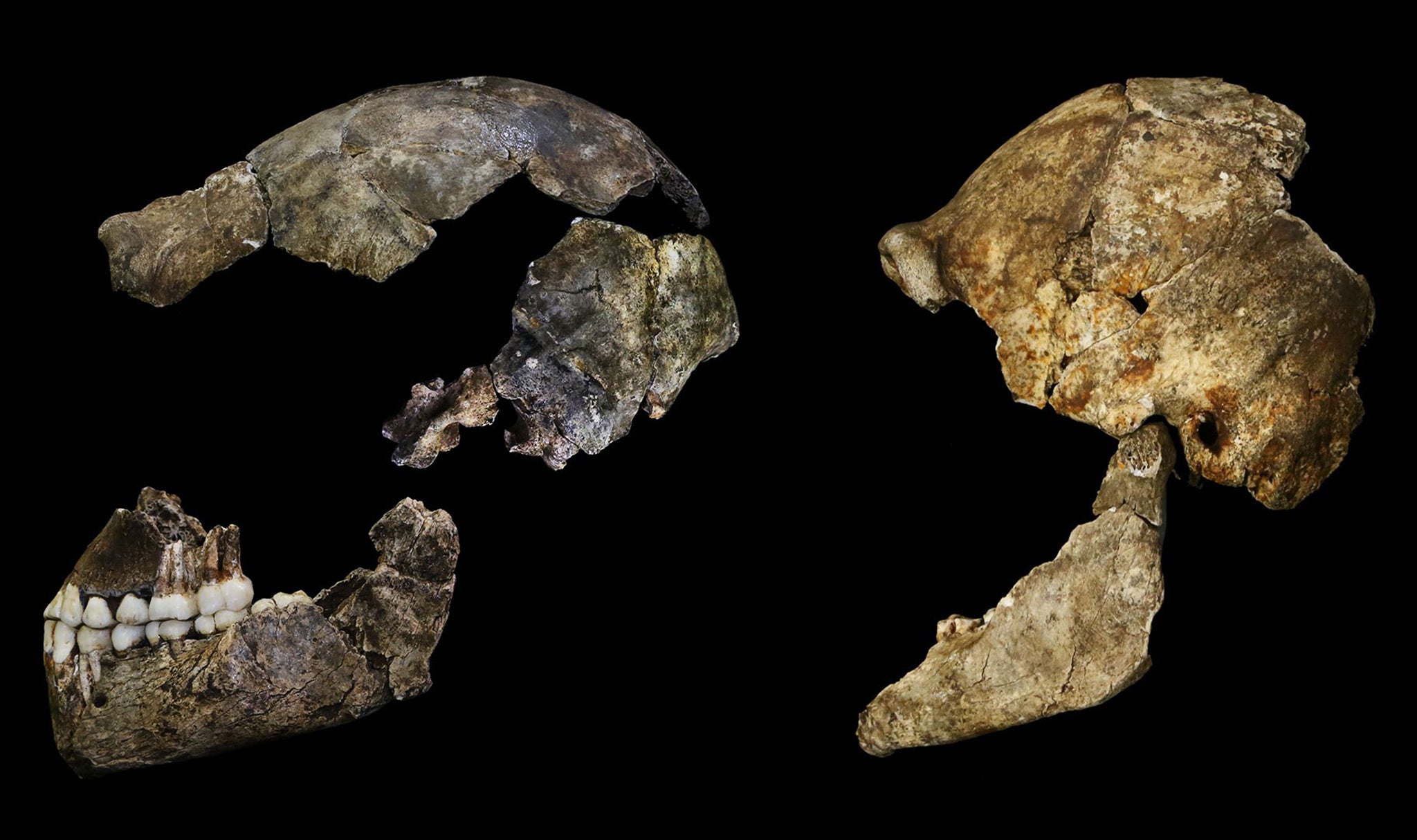

A new species of human has emerged from the stunning discovery of the greatest single assemblage of fossilised skulls and bones ever found in Africa – the continent where the story of human origins first began.

Deep within a concealed chamber at the back of an underground cave in South Africa, scientists have unearthed more than 1,550 fragments of at least 15 skeletons belonging to a species that the researchers believe is a new member of the human family.

Never before in Africa have palaeontologists had access to so many bones belonging to a single human species. They have found multiple examples of almost every bone in the body of Homo naledi, the name given to the latest member of the Homo genus.

Perhaps the most surprising and intriguing part of the discovery, however, is that these diminutive humans, who grew no taller than about 5 feet and had a brain no bigger than an orange, seem to have buried their dead in a ritualistic manner – something considered to be unique to anatomically-modern humans.

Studies of the skeletons have revealed that the feet of H. naledi were similar to those of modern people, with relatively long legs for distance walking. However, its fingers were deeply curved with gripping fingertips, suggesting that it was also happy with climbing trees.

Some parts of the skeleton, such as the hips, show “primitive” features of early ape-like species while others, such as its small, simple teeth, are more like modern humans. However, scientists believe H. naledi represents an early member of the human family, possibly among the first members of the genus Homo, who may have lived more than 2 million years ago – although the age of the fossilised bones from the cave has yet to be dated.

“Overall, H. naledi looks like one of the most primitive members of our genus, but it also has some surprisingly human-like features, enough to warrant placing it in the genus Homo,” said John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and senior member of the international research team.

“H. naledi had a tiny brain, about the size of an orange – about 500 cubic centimetres – perched atop a very slender body….It’s a creature that looks like no other hominin before,” Professor Hawks said.

The brains of modern humans by comparison are about three times the size, he added. “H. Naledi connects to our family tree somewhere among the earliest members of our genus. It was at the root of our genus Homo,” he said.

Access to the burial chamber at the back of the cave, known as Rising Star or “Naledi”, is up a steep incline called the dragon’s back running up the side of an antechamber some 80 metres inside the cave. The potholing involved was so difficult because of the narrowness of the shaft leading to it that the scientists had to use social media to recruit slim-line cavers small enough to squeeze through a 10-inch gap.

Studies have shown that the inner burial cavern, called the Dinaledi chamber, contains the remains of males and females as well as children and adults, with one skeleton being of a very young child and another belonging to an elderly person. Scientists believe bodies were carried manually into the cave over many years rather than being the result of a single, catastrophic mass death – in other words they were buried as part of a repeated, ritual act.

“We have just met a new human relative that deliberately disposed of its dead,” said Professor Lee Berger of the University of Witwatersand in Johannesburg, who led the two expeditions that discovered and then recovered the fossils from the cave, which is 30 miles (50km) northwest of Johannesburg.

One of the greatest mysteries was how so many skeletons managed to end up in the cave’s Dinaledi chamber, which has never had direct access to the outside, is in perpetual darkness and was never subjected to floods that could carry human or animals remains into the cavern.

“We have a cave full of petit individuals who are all cramped into a small chamber and the question is how did they get there?” said Professor Paul Dirks of James Cook University in Queensland, Australia.

Because of the absence of other animals bones, apart of a few rodents, the scientists have eliminated the possibility of the bodies being carried their by scavengers. The roof of the cavern suggests there has never been a shaft leading to the surface. This has led them to conclude that the bodies were deliberately taken there to be buried, Professor Berger said.

“We explored every alternative scenario, including mass death, an unknown carnivore, water transport from another location, or accidental death in a death trap, among others,” he said.

“We were left with intentional body disposal by Homo naledi as the most plausible scenario,” he added.

How the fossils were found

Two cavers, Rick Hunter and Steven Tucker, were exploring the inner chamber of the Rising Star cave situated about 30 miles from Johannesburg when they noticed a narrow fracture system at the back of the cave at the top of a steep incline known as the Dragon’s Back.

They had found the entrance to an unexplored part of the cave known as the Dinaledi chamber. The entrance to this chamber is down a steep, narrow shaft and once inside they noticed fossil fragments which led to the involvement of Professor Lee Berger, a palaeontologist at Witswatersand University.

The chamber was so difficult to get to, Professor Berger decided to use social media to call on the expertise of amateur cavers small enough to squeeze through the 18 cm (8 inch) fracture. Most of the recruits were petite women who became known as the “underground astronauts” because of the inhospitable environment they had to work in.

In two expeditions between November 2013 and March 2014, more than 60 cavers and 50 scientists worked on locating and retrieving more than 1,550 fragments of fossilised bones from 15 individuals who had been deliberately buried in the inner Dinaledi chamber, some 80 metres (100 yds) from the entrance to the underground cave.

“This chamber has not given up all its secrets. There are potentially hundreds if not thousands of remains of Homo naledi still down there,” Professor Berger said.

Other species of Homo

H. habilis: “Handy man” lived in Africa between 1.5 million and 2.1 million years ago. Is the oldest known member of the Homo genus.

H. erectus: “Upright man” is a robust species that roamed far and wide outside of Africa. Lived from 1.8 million years ago to as recently as 70,000 years ago.

H. rudolfensis: Found at two sites in Kenya, dated to about 1.9 million years ago with a larger brain size than earlier H. habilis.

H. ergaster: Sometimes classified as H. erectus, found at sites in eastern and southern Africa.

H. antecessor: Also sometimes classified as H. heidelbergensis, found in Spain and lived between 1.2 million years and 800,000 years ago.

H. neanderthalsis: Neanderthal man, lived from Central Asia to western Europe, adapted to cold conditions with short, thick-set body. Lived as recently as 35,000 years ago.

H. floresiensis: The miniature species of “Hobbit” who lived on the island of Flores in Indonesia with a brain the size of an orange.

Denisova man: Possibly an early member of H. sapiens, but with some Neanderthal lineage. Live in Siberia about 40,000 years ago.

Red Deer Cave people: Another possible early H. sapiens who lived in China about 14,000 years ago and hunted red deer.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks