Neanderthals built mysterious structures that could completely change understanding of humanity’s origins

Similar finds have probably been lost to time – as we might never really know what spurred our ancient relatives to build the unusual structures

Strange ring-shaped structures that were made about 176,000 years ago could change our understanding of our closest extinct relatives.

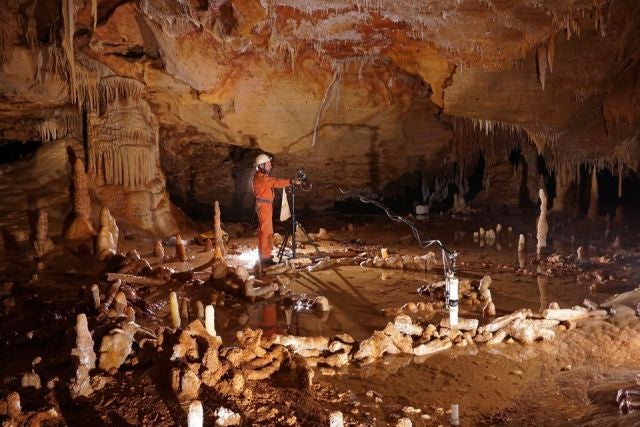

The strange structures, fashioned out of broken stalagmites deep inside a cave in southwestern France, appear to show that Neanderthals were far more adept than had previously been thought.

The mysterious arrangements, deep in a dark cave, could be an indication that they were used for “ritual social behaviour”. And there may have been many similar examples of Neanderthal culture that have since been lost, according to experts.

The structures were made out of hundreds of stalagmites – pillar-shaped mineral deposits. They were each chopped to a similar length and then put into oval patterns that go 16-inches high.

They were found by accident in 1990, after they were cut off for tens of thousands of years by a rockslide that shut the mouth of the cave.

Previous research had shown that the structures came before humans arrived in Europe about 40,000 years ago. But the idea that they had been fashioned by Neanderthals was a problem for some who believed that our ancient relatives wouldn’t have had the kind of complex behaviour required to make them while working underground.

But using new and sophisticated dating techniques, researchers have shown that the stalagmites must have been broken off 176500 years ago – "making these edifices among the oldest known well-dated constructions made by humans”, according to the team led by archaeologist Jacques Jaubert of the University of Bordeaux.

"Their presence at 336 meters (368 yards) from the entrance of the cave indicates that humans from this period had already mastered the underground environment, which can be considered a major step in human modernity," the researchers concluded in a study published in Nature.

The research rules out theories that the rings came about by chance or have been assembled by other animals.

To build the strange structures, the Neanderthals must have decide on a “project” to go deep into the cave and outside the reaches of natural light, according to Professor Jaubert. It’s likely that they went into the cave as a group and lit it using fire – traces of which can still be found on the structures.

Paola Villa, an archaeologist at the University of Colorado at Boulder who wasn't involved in the study, said the site "provides strong evidence of the great antiquity of those elaborate structures and is an important contribution to a new understanding of the greater level of social complexities of Neanderthal societies."

There might have been even more examples of Neanderthal culture that have since been lost, according to Wil Roebroeks, a Neanderthal expert at the University of Leiden, Netherlands.

"Bruniquel cave (shows) that circular structures were a part of Neanderthals' material culture," said Roebroeks, who called the rings "an intriguing find, which underlines that a lot of Neanderthal material culture, including their 'architecture,' simply did not survive in the open."

We have previously found other Neanderthal structures, like hearths and rock workshops. But we have never before found “structures of this magnitude, and in this deep cave context,” said Professor Jaubert.

Not having found any other similar structures makes it very difficult to understand exactly what they were used for or how they came about, according to researchers.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks