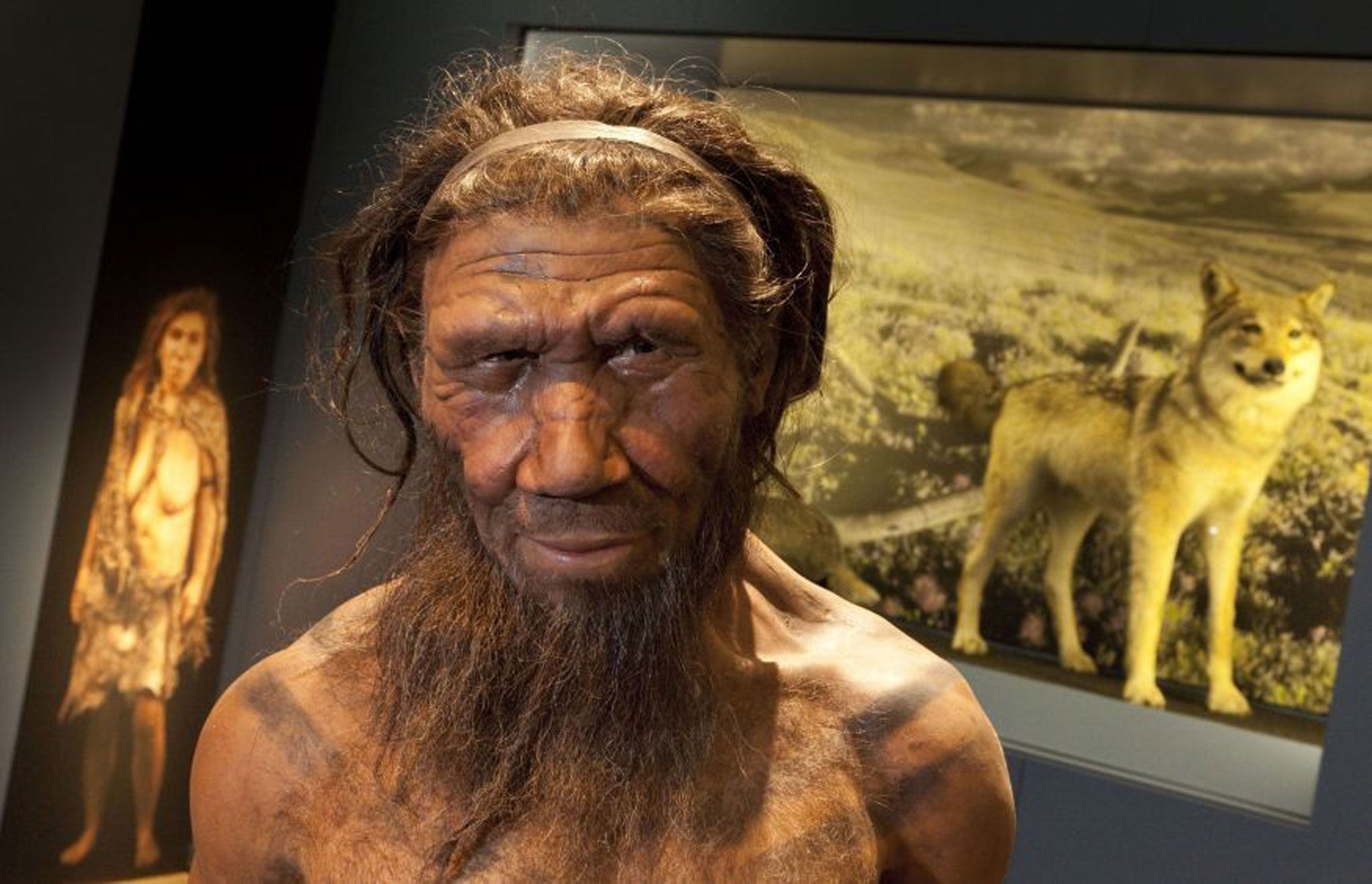

Interbreeding with Neanderthals gave humans ability to fight off dangerous diseases

DNA from long-extinct species survives in many modern people and may have helped defend against diseases similar to flu and hepatitis

Modern humans have the ability to fight off infections like flu and hepatitis because of the Neanderthal DNA they inherited from their ancestors, new research has found.

Around 70,000 years ago, humans began migrating out of Africa , but when they arrived in Eurasia they found they were not alone. Neanderthals had been living in the region for hundreds of thousands of years, and their bodies were well-adapted to its harsh climate.

Homo sapiens, by contrast, would have been suited to the savannahs of Africa and crucially to the diseases that thrived there.

So as humans began to interact with Neanderthals, they would have been easy targets for harmful viruses as their immune systems would have been unable to defend them.

Interbreeding between these ancient human groups has left many modren Europeans and Asians with 2 per cent Neanderthal DNA.

“Modern humans and Neanderthals are so closely related that it really wasn’t much of a genetic barrier for these viruses to jump,” said Professor David Enard, a geneticist at the University of Arizona. “But that closeness also meant that Neanderthals could pass on protections against those viruses to us.”

Research conducted by Professor Enard while he worked under Professor Dmitri Petrov at California's prestigious Stanford University has revealed this protection is part of the reason snippets of Neanderthal DNA have survived thousands of years after the species vanished.

“Many Neanderthal sequences have been lost in modern humans, but some stayed and appear to have quickly increased to high frequencies at the time of contact,” said Professor Petrov. “We believe that resistance to specific RNA viruses provided by these Neanderthal sequences was likely a big part of the reason for their selective benefits.”

Publishing the findings in the journal Cell, they said they had identified 152 genes inherited from Neanderthals, coding for substances that interact with viruses made from ribonucleic acid (RNA). This group that includes influenza, hepatitis C and HIV.

These interactions suggest a role for these genes in the fight against these viruses throughout human history.

Rather than evolving their own immune defences against these diseases, the team’s results suggest that the offspring of Neanderthal-human couplings were given a genetic toolkit to tackle them.

“It made much more sense for modern humans to just borrow the already adapted genetic defences from Neanderthals rather than waiting for their own adaptive mutations to develop, which would have taken much more time,” said Prof Enard.

These genes proved so useful they helped our ancestors to survive, but they also remained in the population and are still present in modern Europeans.

Noting that the genes they identified were not present in today’s Asians, who also share some Neanderthal DNA, the scientists said that the survival of genes would have depended on the setting and the diseases present there.

In the case of the potential virus-fighting genes their study unearthed, they could be evidence of disease that are long gone. Studying human genomes in this way therefore provides a unique insight into the ancient history of epidemics.

Previous research has suggested that the exchange of diseases between ancient humans was likely a two way street, with people bringing exotic diseases including tapeworm, TB and herpes from Africa that may even have contributed to Neanderthals’ ultimate demise.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks