How many of the moon’s craters are named for women?

When Bettina Forget researched the names of moon craters, she found that of the 1,578 that had been named, only 32 honoured women. Now she’s trying to highlight that under-representation, writes Katherine Kornei

The moon’s surface is pockmarked with craters, the relics of violent impacts over cosmic time. A few of the largest are visible to the naked eye and a backyard telescope reveals hundreds more. But turn astronomical observatories or even a space probe on our nearest celestial neighbour and suddenly millions appear.

Bettina Forget, an artist and researcher at Concordia University in Montreal, has been drawing lunar craters for years. Forget is an amateur astronomer and the practice combines her interests in art and science. “I come from a family of artists,” she said. “I had to fight for a chemistry set.”

Moon craters are named, according to convention, after scientists, engineers and explorers. Some that Forget draws have familiar names: Newton, Copernicus, Einstein. But many do not. Drawing craters with unfamiliar names prompted Forget to wonder: Who were these people? And how many were women?

“Once this question embeds itself in your mind, then you’ve got to know,” she says.

Forget pored over records of the International Astronomical Union, the organisation charged with awarding official names to moon craters and other features on worlds around the solar system. She started underlining craters named after women.

“There was not much to underline,” Forget said.

Of the 1,578 moon craters that had been named at that time, only 32 honoured women (a 33rd was named in February).

“I didn’t expect 50 per cent. I’m not that optimistic,” she said. “But two per cent? I was really shocked.”

Having so few moon craters named after women makes a powerful statement, she said. “It creates an atmosphere where you think women aren’t contributing.”

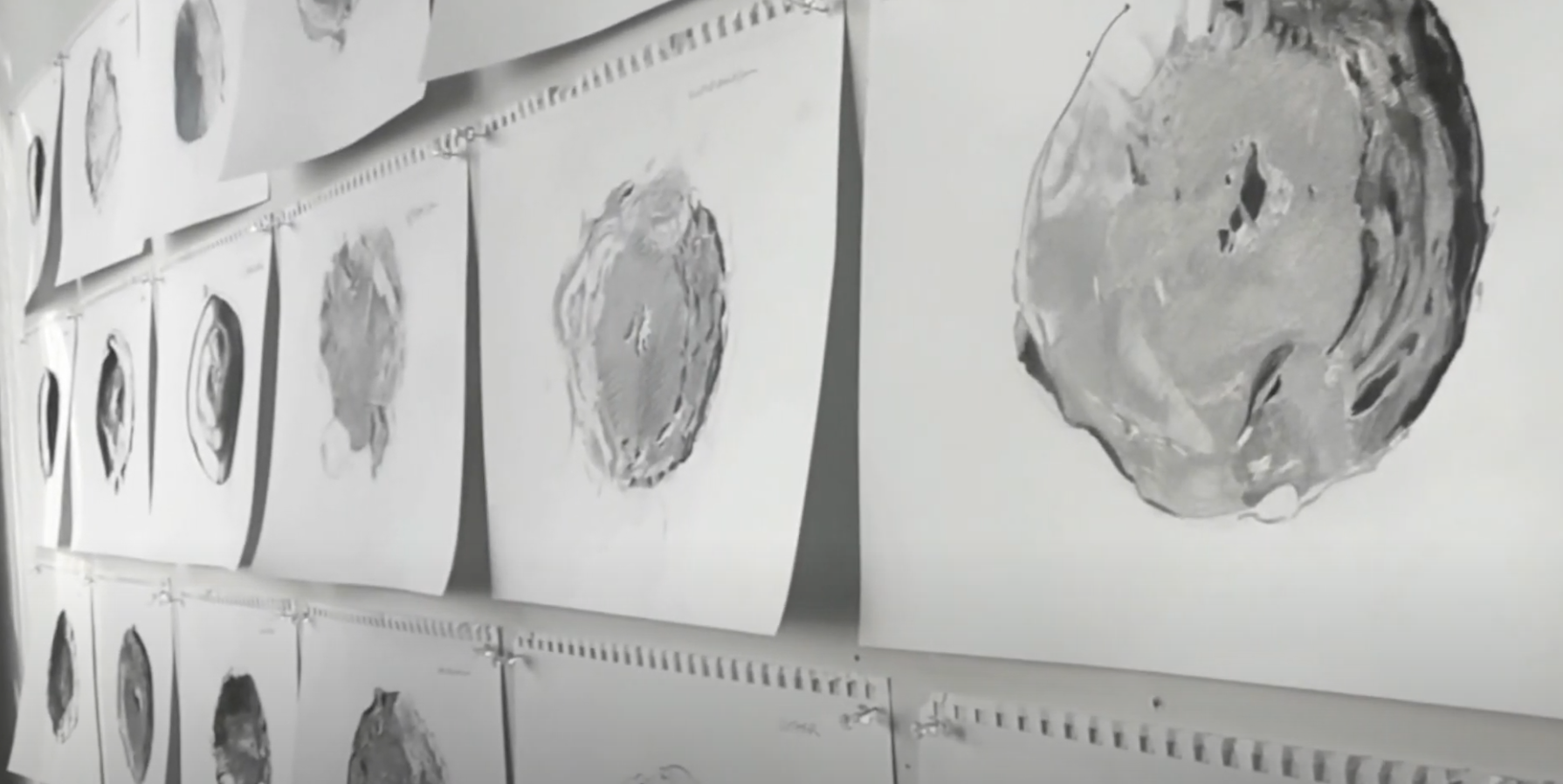

In 2016, Forget embarked on a project called Women With Impact, drawing each crater named after a woman. Forget draws in a large notebook using graphite for detailing and black acrylic paint. She captures the likeness of craters on the near side of the moon – such as Cannon and Mitchell, namesakes of 19th- and 20th-century female astronomers – by observing them with her 8in telescope. For craters such as Resnik and Chawla, both named after female astronauts and located on the far side of the moon that’s not visible from Earth, she bases her drawings on images taken by Nasa’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Women are overrepresented when it comes to the names of features on Venus and some of Uranus’s smaller moons. But those places are exceptions in the solar system

Forget has so far completed all 32 drawings. The pieces, all individually framed, have been displayed at an art gallery at Bishop’s University, Quebec, and the Rio Tinto Alcan Planetarium in Montreal. Women With Impact is meant to highlight the underrepresentation of women in Stem (science, technology, engineering and maths) professions, Forget says. “A crater is an absence of matter, a void,” she says. “That’s a parallel with a void of women in Stem.”

Working with craters in two dimensions led Forget to add a third. “I liked this idea of holding a moon crater in my hand,” she says. In 2019, she began 3D printing models of each crater featured in Women With Impact. Forget is now creating an inverted version of each one, essentially a stamp that preserves the crater’s shape. “I could do an outie,” she says.

Forget is experimenting with different ways of affixing those stamps to the soles of shoes. She plans to send the stamps to female scientists around the world and ask them to record their experiences creating their own craters in a project called One Small Step. As the director of the Artists in Residence programme at research organisation Seti Institute in California, Forget intends firstly to reach out to women whose work focuses on astrobiology and exoplanets.

It’s important to celebrate the contributions of living female scientists, Forget says. “The Women With Impact series honours historical women but One Small Step can honour and foreground women who are active in Stem fields now,” she says.

As more moon craters are named for women, Forget plans to create additional drawings, 3D models and stamps. She already has work to do – one crater, Easley, was named in February after computer scientist Annie Easley.

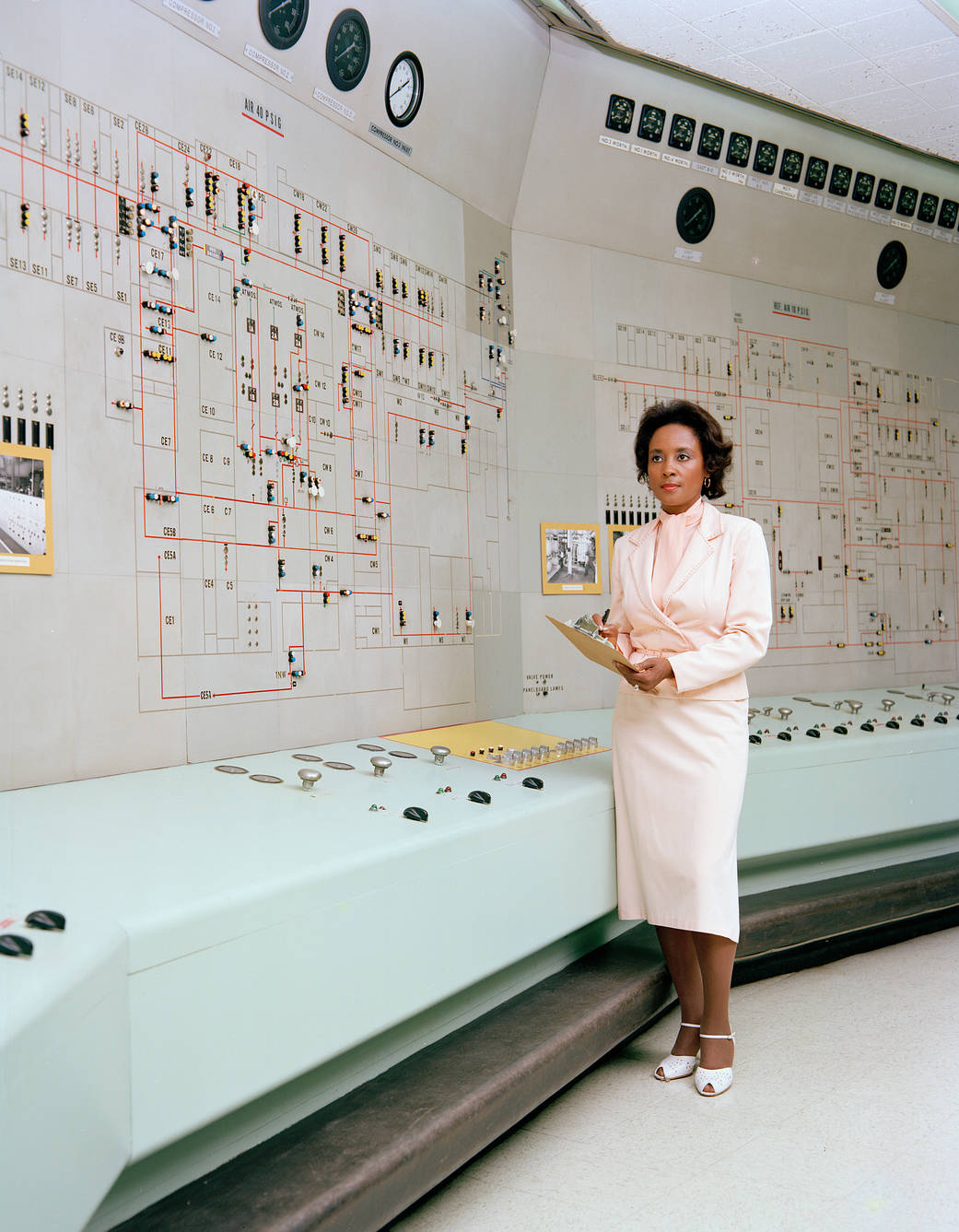

Catherine Neish, a planetary scientist at the University of Western Ontario, proposed the name Easley to the International Astronomical Union in January. Her husband had urged her to consider not only the name of a woman but also the name of a woman of colour. Neish had successfully proposed craters Pierazzo and Tharp in 2015 after planetary scientist Elisabetta Pierazzo and ocean cartographer Marie Tharp and she was aware of the small fraction of moon craters honouring women. “I was gung-ho to slowly chip away at that number,” she says.

The paucity of moon craters honouring women is both surprising and not surprising, said Kelsi N Singer, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute, Texas. Women generally weren’t allowed to be scientists, engineers and explorers until the 20th century, she says and because lunar craters are not typically named for living people, “there’s definitely a historical lag”.

Women are overrepresented when it comes to the names of features on Venus and some of Uranus’s smaller moons. But those places are exceptions in the solar system. The International Astronomical Union has acknowledged this issue and is prioritising women’s names when naming moon craters.

Read More:

“We decided that if we have the choice and the chance to name a crater after a woman, we do it,” said Rita Schulz, a planetary scientist at the European Space Research and Technology Centre in the Netherlands and chair of the union’s Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature.

Neish already has another name in mind for a moon crater. “Very few people can name craters because they don’t have a valid scientific reason for doing so,” she says. “I want to use my privilege to recognise some of these women who have come before me.”

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks