Tiny sample from corner of Mona Lisa reveals toxic secret hidden inside painting

Ground layers of famous painter’s artworks contain rare lead compound, scientists say

Samples taken from Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic paintings Mona Lisa and the Last Supper suggest the renowned Renaissance artist played around with chemicals, causing a rare toxic compound to form in his artworks.

He experimented with the compound lead(II) oxide, causing the formation of the toxic lead-compound plumbonacrite in a layer beneath the iconic Mona Lisa painting, new research published last week in the Journal of the American Chemical Society suggested.

Previous research has shown that many paintings from the early 1500s, including the Mona Lisa, were painted on wooden panels that required a thick, “ground layer” of paint to be laid down before artwork was added.

While other artists of the time typically used gesso – a compound derived from plaster of Paris – the Italian polymath widely experimented, say scientists, including those from CNRS in France.

They say he began some of his artworks by laying down thick layers of lead white pigment and by infusing his oil with lead(II) oxide – an orange pigment that conferred specific drying properties to the paint above.

He also used a similar technique on the wall underneath the Last Supper, which researchers say is a departure from the traditional, fresco mural painting technique used at the time.

In the latest study, scientists sought to apply updated and high-resolution analytical techniques to small samples from these two paintings.

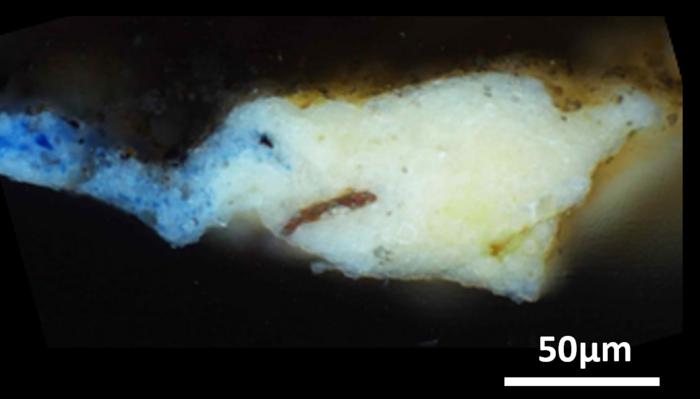

They assessed a tiny “microsample” that was previously obtained from a hidden corner of the “Mona Lisa,” as well as 17 such small samples taken from across the surface of the “Last Supper.”

The study found that the ground layers of these artworks not only contained oil and lead white but also a much rarer lead compound: plumbonacrite [Pb5(CO3)O(OH)2].

While this material had not been previously detected in Italian Renaissance paintings, researchers say it has been found in later paintings by Rembrandt in the 1600s.

Although artists are known to have added lead oxides to pigments to help them dry, this technique has not been proved experimentally for paintings from da Vinci’s time.

During the legendary polymath’s time, the only evidence scientists have found of PbO was in reference to skin and hair remedies, even though it is now known to be toxic.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks