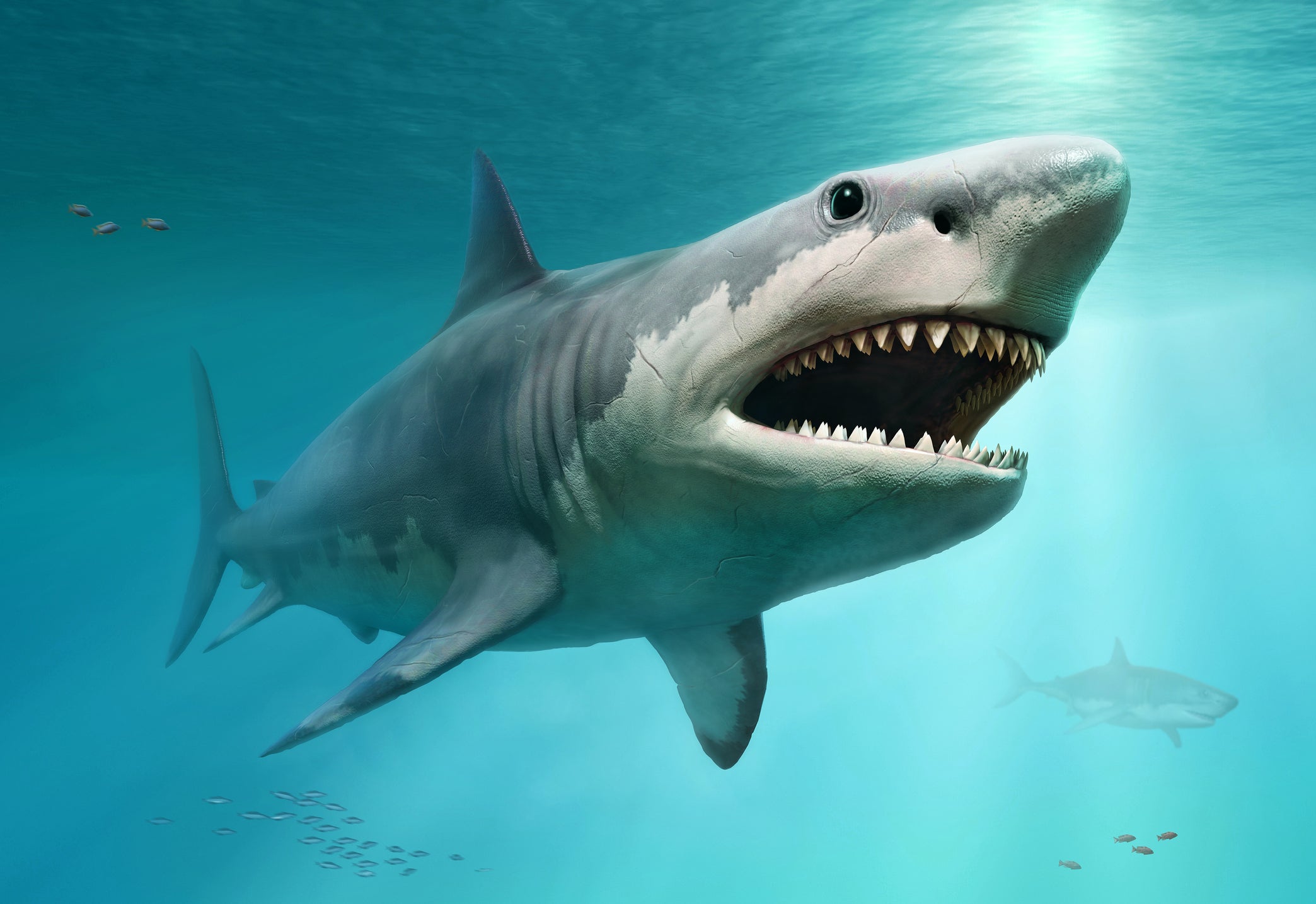

15 million-year-old Megatooth shark grew to 50ft long by feeding on unhatched eggs in the womb, study finds

Analysis of Megalodon vertebrae suggests Miocene-era carnivores could live for a century

Giant megatooth sharks – among the largest predators ever to exist on Earth – grew so large by feeding on the unhatched eggs of their siblings in the womb, new research suggests.

Also known as Megalodons, the now-extinct carnivores dominated the oceans 15 million to 3.6 million years ago, growing up to 50 feet (15 metres) in length.

According to a new study published in the journal Historical Biology, they were typically already larger than most humans when they emerged from the womb, with a length of around 6.6 feet.

This suggests that Megalodons gave live birth to possibly the largest babies in the shark world.

The giant fish has a rich fossil record but, like most other extinct sharks, its biology remains poorly understood because it is primarily known only from its teeth. However, some remains of gigantic vertebrae have been discovered.

In a bid to shed more light on the role large carnivores play in the evolution of marine ecosystems, researchers used a CT scanning technique to analyse incremental “growth bands” – similar to tree rings – in Megalodon vertebral specimens housed in the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences to discover more about the creatures’ reproductive biology, growth and life expectancy.

Measuring up to 6 inches in diameter, the vertebrae were previously estimated to have come from an individual about 30 feet in length, based on comparisons with the vertebrae of modern great white sharks.

The images revealed the vertebrae to have 46 growth bands, thought to form annually, suggesting the Megalodon specimen died at the age of 46.

However, a growth curve model based on the vertebrae appears to indicate a life expectancy of at least 88-100 years, according to lead author Kenshu Shimada, a paleobiologist at DePaul University in Chicago.

And by back-calculating its body length when each band formed, the scientists were able to deduce its likely length at birth – around 6.6 feet – which indicates that the giant sharks were sufficiently large at birth to compete with other predators and avoid being eaten.

“Results from this work shed new light on the life history of Megalodon, not only how Megalodon grew, but also how its embryos developed, how it gave birth and how long it could have lived,” said co-author Martin Becker, of New Jersey’s William Paterson University.

Researchers say the data also suggests that, like all present-day lamniform sharks – a group containing some of the most recognisable species, such as great whites – embryonic Megalodon grew inside its mother by feeding on unhatched eggs in the womb – a practice known as oophagy, a form of intrauterine cannibalism.

The outcome is that only a few embryos will survive and develop, but those that do will be considerably larger at birth. Although likely to be energetically costly for the mother, this process gives newborns an advantage by reducing the chance of being eaten by other predators, Dr Shimada said.

These “early-hatched embryos”, at least in the case of sandtiger sharks, can occasionally even feed on other hatched siblings for nourishment, the researchers noted.

"As one of the largest carnivores that ever existed on Earth, deciphering such growth parameters of O. megalodon is critical to understand the role large carnivores play in the context of the evolution of marine ecosystems," Dr Shimada said.

The discoveries were made by the same team of researchers who established the Megalodon’s vast size in a paper published in October, which noted that sharks were able to grow larger than they had previously after the age of dinosaurs came to an end.

Co-author Matthew Bonnan, of New Jersey’s Stockton University, said: “My students and I examine spiny dogfish shark anatomy in class and to think that a baby Megalodon was nearly twice as long as the largest adult sharks we examine is mind-boggling.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks