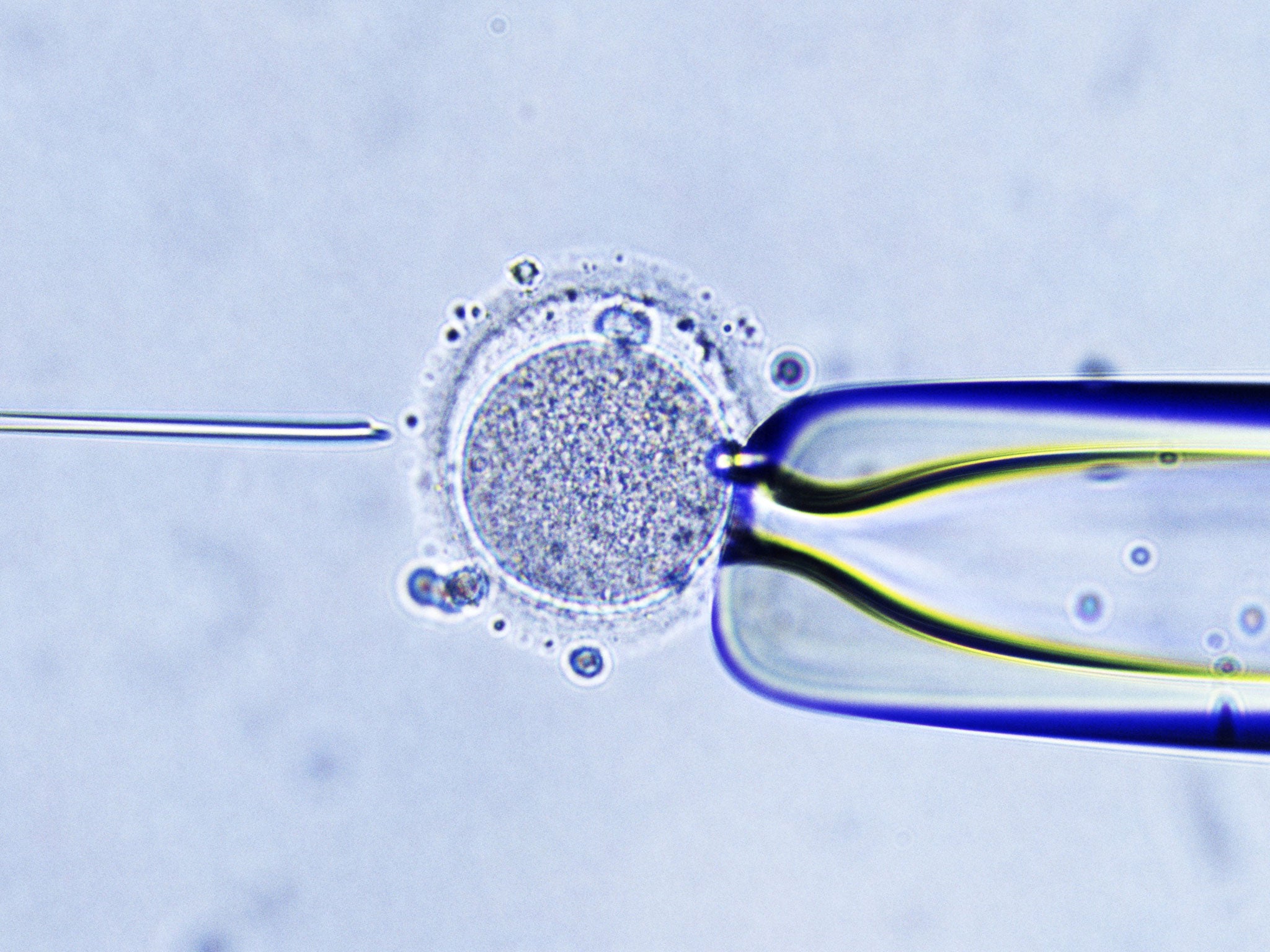

Medical dilemma of 'three-parent babies': Fertility clinic investigates health of teenagers it helped to be conceived through controversial IVF technique

Donor eggs could be used as a way of ensuring that women with mitochondrial defects do not pass on the mutations to their children

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A private fertility clinic in the United States has launched an investigation into the health of 17 teenagers who were born as a result of a controversial IVF technique that produced the world’s first “three-parent” embryos more than 15 years ago, The Independent can reveal.

The technique – which the US government halted in 2002 – involved mixing the eggs of two women so that the resulting IVF babies inherited genetic material from three individuals in a similar process to that planned in Britain for women carrying maternally inherited mitochondrial disorders.

About 30 IVF babies worldwide are believed to have been born by the technique, known as “cytoplasmic transfer”, including 17 infants at the Saint Barnabas Medical Centre in New Jersey who, until now, have not been checked for any long-term health problems resulting from the technique.

How cytoplasmic transfer and mitochondrial donation work

The findings of the follow-up will be keenly scrutinised by Britain’s fertility watchdog, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), which is charged with making sure that a similar technique called mitochondrial donation is safe.

“We do not know of any follow-up of children born as a result of cytoplasmic transfer but we would certainly want to know the results of such a follow-up,” said an HFEA spokesman.

The British government has said it intends to introduce legislation to allow donor eggs to be used as a way of ensuring that women with mitochondrial defects do not pass on the mutations to their children. However, like cytoplasmic transfer, it will result in IVF babies with genetic material from three people – the woman who donated the egg and the child’s two biological parents.

Scientists in the United States announced in 2001 that cytoplasmic transfer had produced the first “genetically modified” babies with DNA from three people but until now there had been no follow-up of the 17 children to find out whether they had developed any long-term health problems as a result.

The Independent understands that the Institute for Reproductive Medicine and Science (IRMS) at St Barnabas finally began a follow-up earlier this year, although it has not released any details of the study and refused to answer questions about the progress of the investigation.

“I appreciate your interest but we are not intending to participate in this piece that you are working on,” Cindy Lucus, director of marketing at the IRMS said in an email.

Any long-term health problems resulting from the technique could be embarrassing for the private IVF clinic, which began cytoplasmic transfer in 1996 as a way of boosting the chances of a successful pregnancy for couples seeking fertility treatment until it was stopped in 2002 after the US Food and Drug Administration intervened.

However, the findings would also be of intense interest to health authorities in both the United States and especially Britain where Parliament is about to decide on whether to make mitochondrial donation legal.

If legislation is passed, the first British child carrying the DNA of three people could be born as early as next year but Parliament will need to be reassured of the long-term health of the children.

Jacques Cohen, the scientist who carried out the cytoplasmic transfer on the 17 IVF babies when he was employed by the IRMS, said the follow-up began earlier this year and that it is being led by Dr Serena Chen, a fertility specialist at the IRMS. “Because the research team members accepted different positions elsewhere, no follow-up was conducted until this year. The current follow-up study is ongoing and results will be made available in a medical journal,” Dr Cohen said in an email.

Dr Cohen, who now works for another private fertility company, called Reprogenetics in Livingston, New Jersey, refused to elaborate.

“You should ask the doctors who are now in charge of the IVF team at Saint Barnabas Medical Centre. Dr Serena Chen is directing the follow up study,” Dr Cohen said.

It is not known whether all 17 teenagers have been located or whether the follow-up study is likely to be completed before Parliament is able to vote on whether to allow mitochondrial donation in Britain. Dr Chen did not respond to our telephone calls or emails.

Cytoplasmic transfer involves injecting small amounts of non-nuclear material, including the energy-producing mitochondria, from a healthy donor egg into the egg of a woman undergoing IVF.

The aim was to improve the success rate of IVF treatment, possibly by boosting the embryo’s complement of mitochondria, the “power packs” of the cells which carry their own genes separately from the chromosomes in the cell nucleus.

Although there are similarities with cytoplasmic transfer, the HFEA said that the two IVF techniques being proposed for mitochondrial donation in the UK are fundamentally different because they involve the replacement of all mitochondria in a mothers egg with the mitochondria of a donor egg – rather than mixing the two together.

When Dr Cohen’s team published a study in 2001 of two babies who were born with mitochondria from two different “mothers”, the scientists wrote that it was “the first case of human germ-line genetic modification resulting in normal healthy children”.

However, it later emerged that there were two pregnancies where embryos had a missing sex chromosome, known as Turner syndrome – one miscarried and the other was aborted. There was also a case where one of the babies who had developed a “pervasive developmental disorder” in the first year of life, Dr Cohen said. “Whether these anomalies were related to the procedure is unknown. The fact is that the parents could not become pregnant on their own or after conventional IVF. This could have also been the cause of the [Turner syndrome],” Dr Cohen said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments