New state of matter made from atoms inside other atoms discovered by physicists

Scientists show 'Rydberg polarons' can be created by increasing orbit of electrons at temperatures approaching absolute zero

A new state of matter made up of “giant atoms” filled with other, normal atoms, have been revealed in experiments.

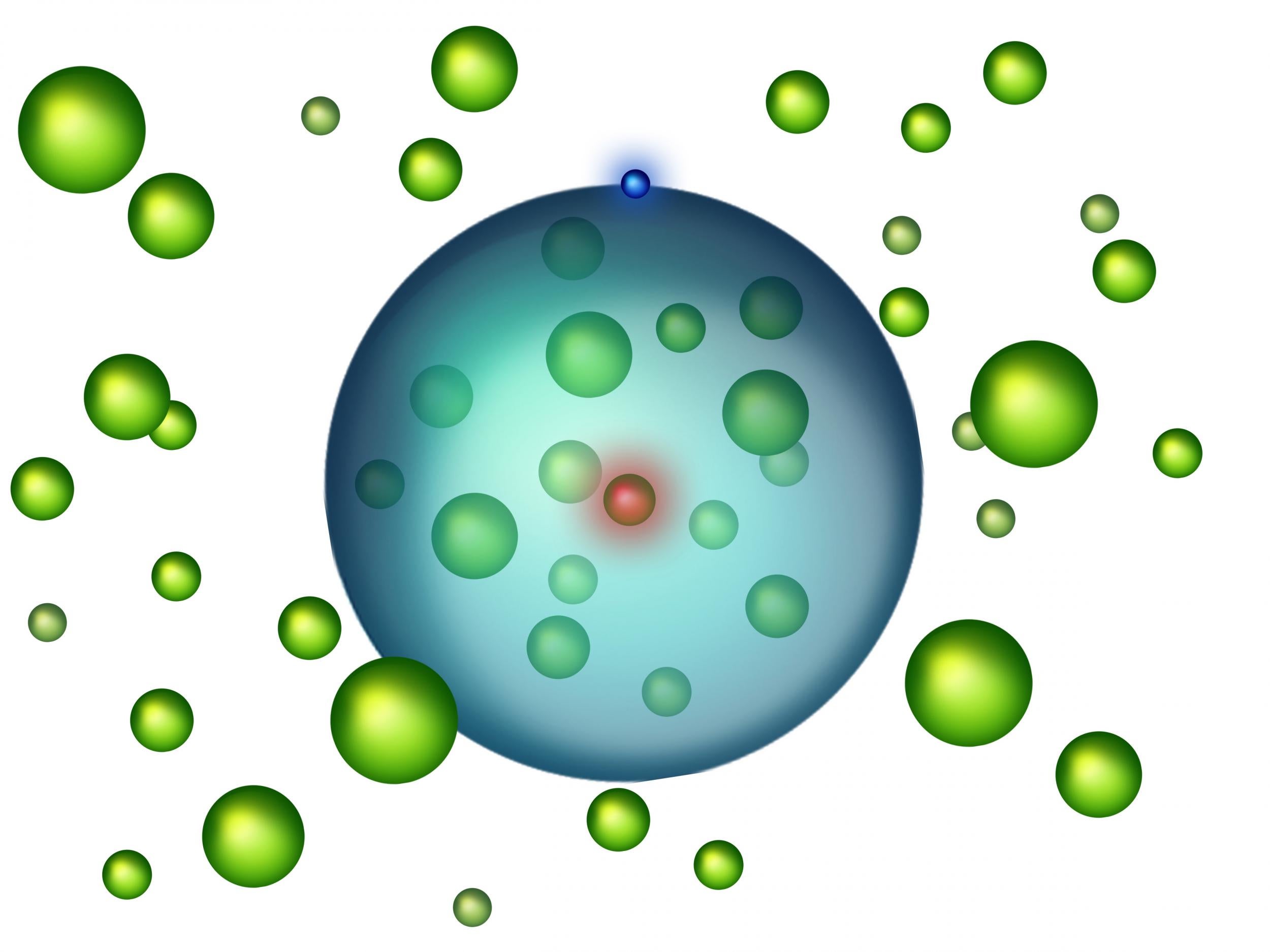

Called Rydberg polarons, they can be created if an electron can be encouraged to orbit the nucleus of an atom at a distance, it leaves a considerable space that can be filled with something else.

Atoms in this state are called Rydberg atoms.

“The average distance between the electron and its nucleus can be as large as several hundred nanometres – that is more than a thousand times the radius of a hydrogen atom”, said Professor Joachim Burgdorfer, a physicist at TU Vienna and one of the study’s co-authors.

The “something else” in the case of a Rydberg polaron is another atom, or more accurately hundreds of other atoms.

The study was published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Professor Burgdorfer and his colleagues created a Bose-Einstein condensate - a state of mater in which atoms are cooled almost to absolute zero - from atoms of strontium.

At this incredibly cold temperature, the scientists transferred energy to one of the strontium atoms using a laser – turning it into a Rydberg atom with a huge atomic radius.

The orbit of the electron was so large in their new atom that it encompassed other surrounding atoms in the condensate.

Depending on the size of the new orbit they had created and the density at which the atoms were packed in their condensate, the researchers found that close to 200 additional strontium atoms could be encompassed by the electrons in the newly created Rydberg polarons.

The atoms contained within the Rydberg atom’s orbit do not influence its electrons path very much, as they do not carry any electric charge.

However, there is a slight interaction, which creates a bond between the Rydberg atom and the normal atoms.

“It is a highly unusual situation”, says Professor Shuhei Yoshida, another TU Vienna physicist who also contributed to the study. “Normally, we are dealing with charged nuclei, binding electrons around them. Here, we have an electron, binding neutral atoms.”

Owing to the weakness of their bonds, the resulting Rydberg polarons can only exist at very low temperatures.

“For us, this new, weakly bound state of matter is an exciting new possibility of investigating the physics of ultracold atoms”, said Professor Burgdorfer. “That way one can probe the properties of a Bose-Einstein condensate on very small scales with very high precision.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks