Extinct Australian ‘marsupial lion’ that pounced on prey completely reconstructed for first time

Powerful limbs would have made extinct predator adept at ambushing prey

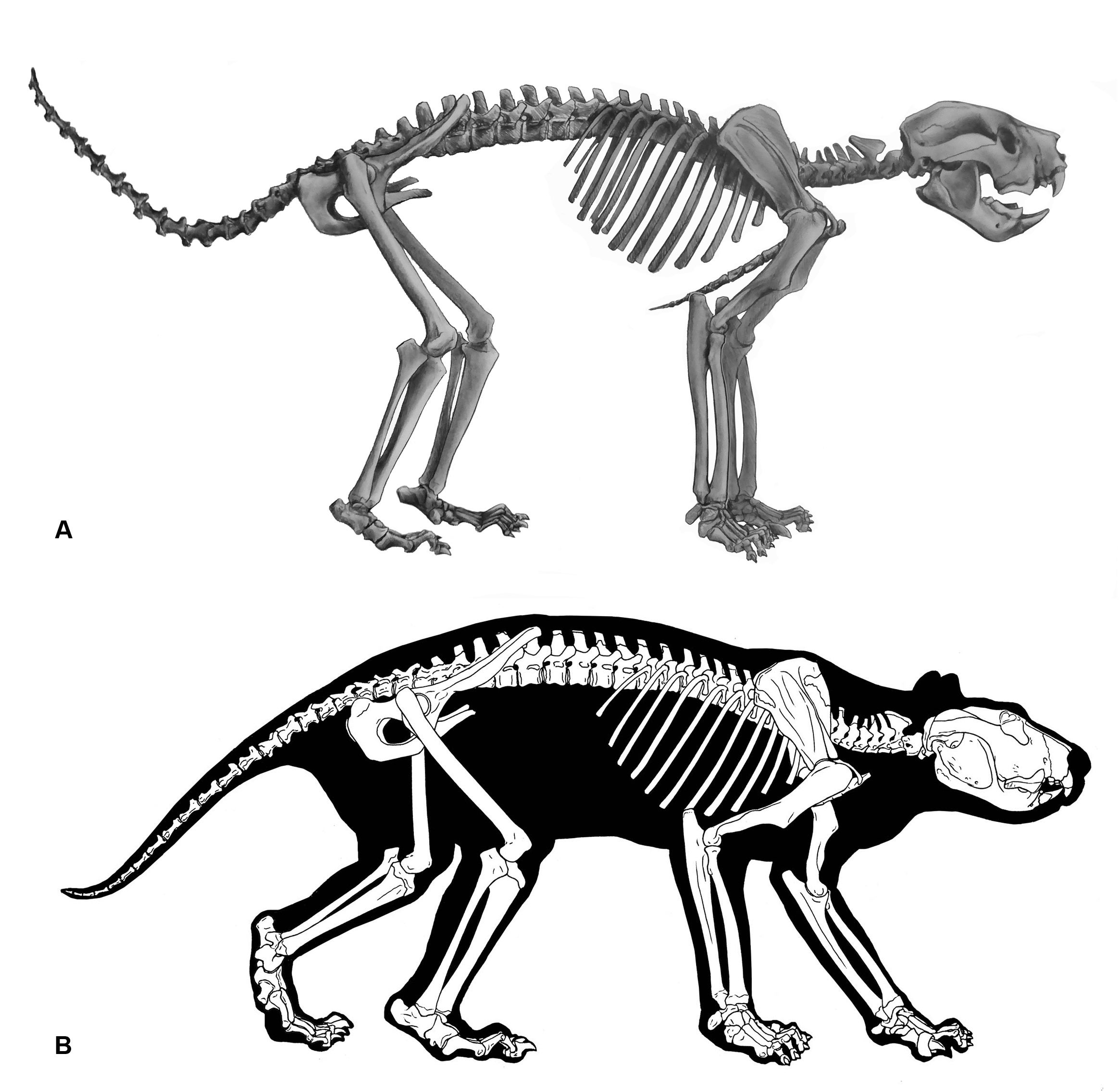

A fearsome marsupial lion that once prowled the Australian outback has been reconstructed from fossilised remains unearthed in caves.

After a nearly complete skeleton was discovered in western Australia, scientists were able to piece together an accurate picture of the predator for the first time.

They revealed a creature with powerful forelimbs for ambushing prey and a rigid tail upon which it would balance while eating, much like kangaroos do today.

Thyalacoleo carnifex – commonly known as marsupial lions – are members of Australia’s “megafauna”, a group of large creatures that disappeared around 30,000 years ago.

The arrival of humans on the continent may have been a factor in their disappearance due to excessive hunting, and specifically the use of fire to drive out prey.

However, climate change could also have played a role in their extinction as Australia grew steadily more arid.

Though Thyalacoleo had some characteristics in common with surviving marsupials – probably including the pouches they used to rear their young – they remain unlike any other living animals.

For decades palaeontologists, have attempted to deduce what their lives might have been like from the fragmented remains available.

But now using new specimens containing bones that had never previously been found, two researchers from Flinders University have assembled the most accurate picture yet.

“The extinct marsupial lion, Thylacoleo carnifex, has intrigued scientists since it was first described in 1859 from skull and jaw fragments collected at Lake Colongulac in Victoria,” they wrote in the journal PLOS One.

“Recent cave finds have for the first time enabled a description and reconstruction of the complete skeleton, including the hitherto-unrecognised tail and clavicles.”

The analysis by Professor Rod Wells and Dr Aaron Camens suggested it had a heavily muscled tail that would have formed a tripod with its back legs as it handled its food or climbed.

Powerful forelimbs combined with a rigid lower back would have meant that while the marsupial lion was not able to chase its prey, it would have been well adapted to jump out and grapple with it.

Their results suggested that the closest living creature to Thylacoleo is neither a lion nor a large marsupial like a kangaroo, but the distantly related Tasmanian devil.

Like the devils, the scientists suggested that besides being ambush hunters the marsupial lion may have used its massive legs to rip apart scavenged carcasses as well.

The skeleton reconstruction also confirmed their closest relatives from the period were diprotodons – a group of enormous wombats that are the largest known marsupials to have ever lived.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks