Evidence of hot water that’s essential to life points to Mars’ habitable past

Researchers used the famous ‘Black Beauty’ meteorite to find ‘fingerprints’ of water-rich fluids

Researchers have uncovered what may be the oldest direct evidence of hot water activity on Mars, suggesting the red planet could have supported life billions of years ago.

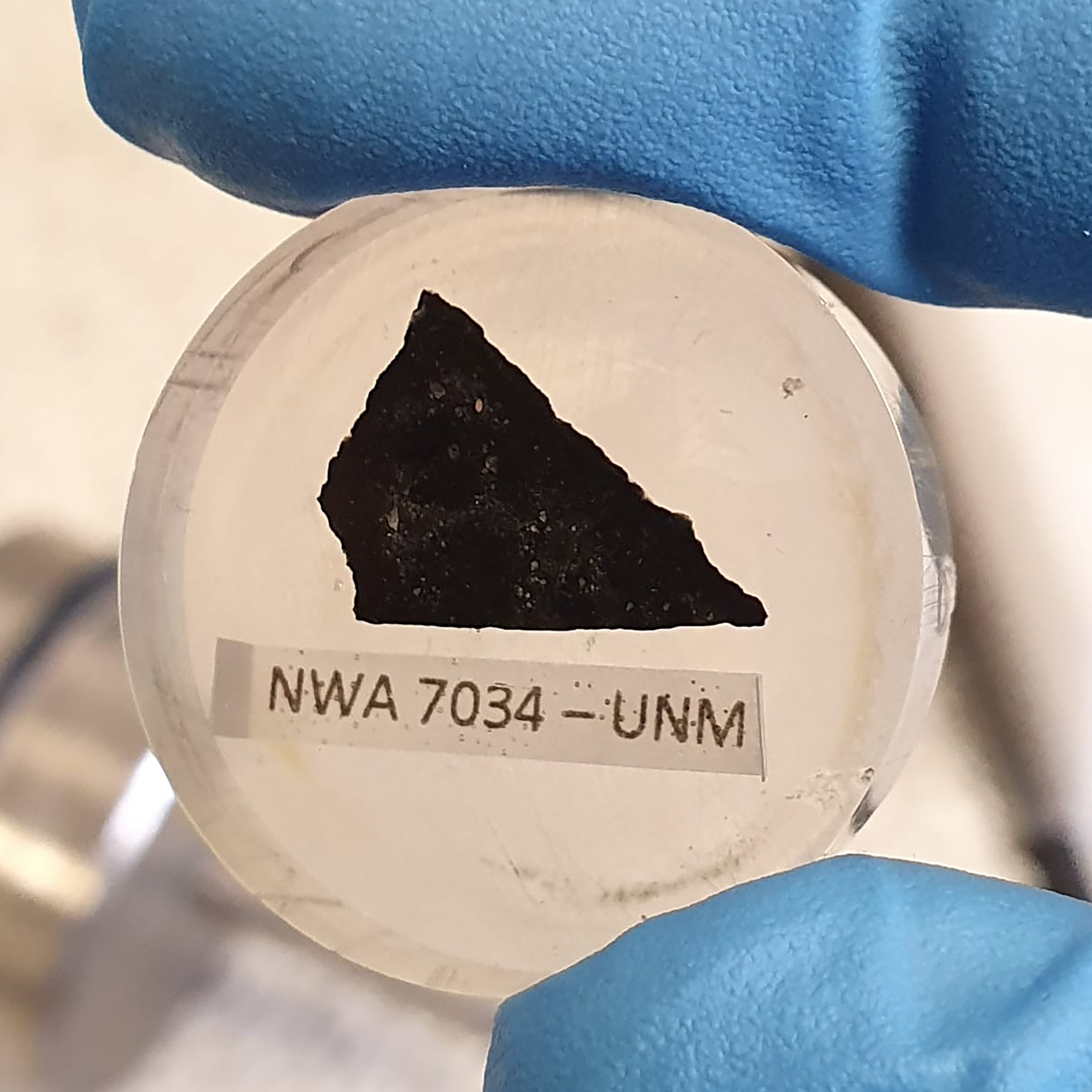

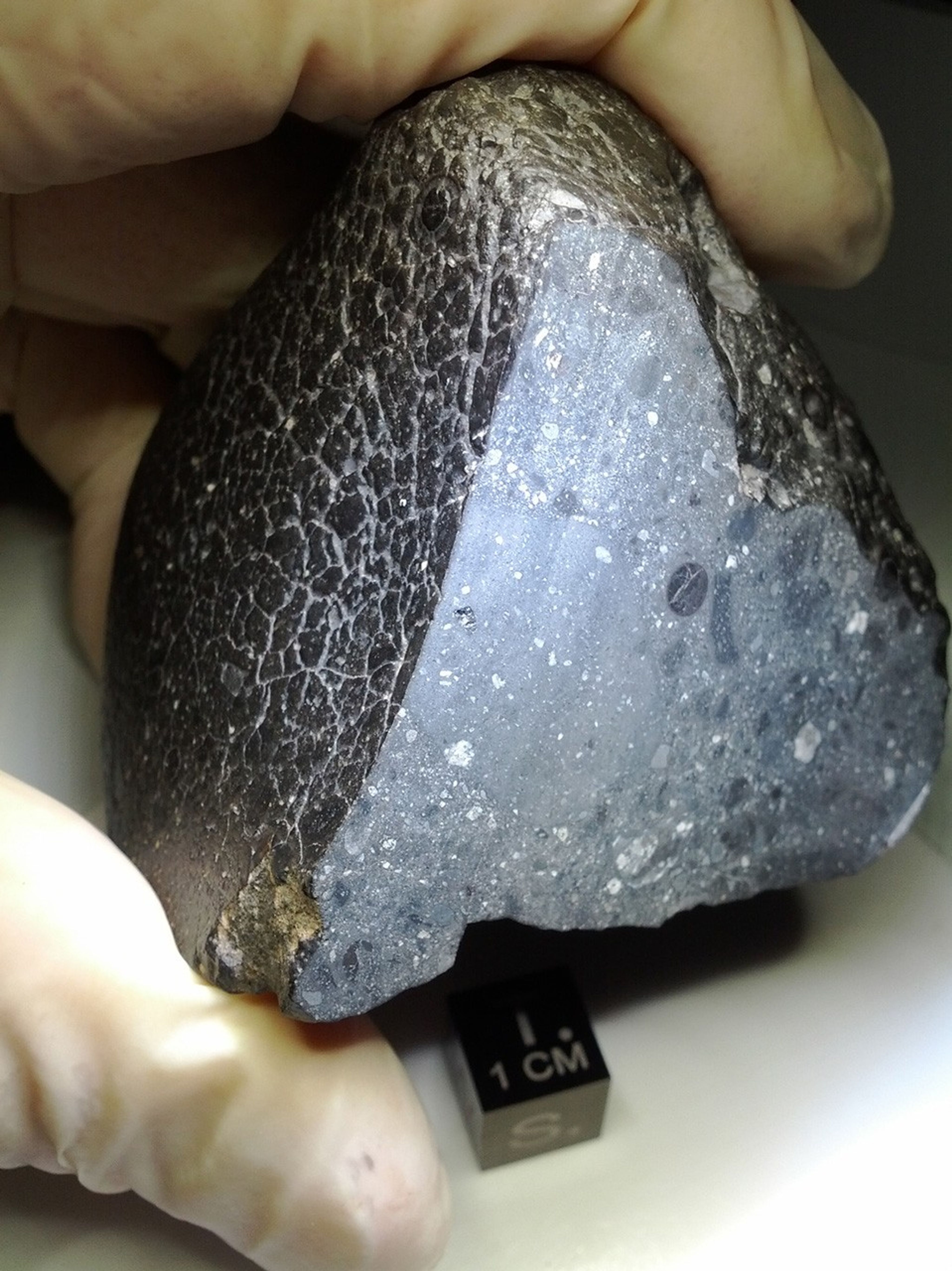

Scientists at Australia’s Curtin University made the discovery while studying a famous Martian meteorite — nicknamed “Black Beauty” — that was found in the Sahara Desert in 2011. The rock, which was created by rapidly cooled lava, contains 10 times more water than other Martian meteorites and formed more than 2 billion years ago.

Analyzing the chemical composition of the meteorite’s 4.45 billion-year-old zircon grain — a mineral that is typically only a few millimeters in size and formed in rocks that have been altered by hot fluids — they found “fingerprints” of water-rich fluids.

“Hydrothermal systems were essential for the development of life on Earth and our findings suggest Mars also had water, a key ingredient for habitable environments, during the earliest history of crust formation,” Dr. Aaron Cavosie said in a statement.

Cavosie is a co-author of a study on the work that was published Friday in the journal Science Advances.

Using nano-scale imaging and spectroscopy, scientific techniques that are conducted with high-powered microscopes, the team identified element patterns in the zircon, including iron, aluminum, yttrium, and sodium.

“These elements were added as the zircon formed 4.45 billion years ago, suggesting water was present during early Martian magmatic activity,” Cavosie explained.

Water was first discovered on Mars in 2008 by NASA’s Phoenix Mars lander. The agency’s rovers have been exploring the Martian surface and looking for the ingredients and signs of ancient microbial life for years. Since then, researchers have found evidence of a large underground reservoir of liquid water — enough to fill oceans on the planet’s surface. They also believe water flowed on Mars fairly recently, and in 2020, Arizona scientists said Mars may have been home to hot springs.

“If these were hot springs, looking at them could potentially tell us something about habitable environments for extremophiles,” Jessica Barnes, of the University of Arizona, said then. They could have been the best places for life to develop on Mars.

This new discovery has opened up new avenues for understanding the planet’s past habitability and understanding its hydrothermal systems.

Cavosie said the research showed that even though Mars’ crust was hit by massive meteorites that caused a major upheaval of the planet’s surface, water was present during the early Pre-Noachian period, prior to about 4.1 billion years ago.

“This new study takes us a step further in understanding early Mars, by way of identifying tell-tale signs of water-rich fluids from when the grain formed, providing geochemical markers of water in the oldest known Martian crust,” he said.

In 2022, a study of the same zircon grain found it had been “shocked” by a meteorite impact, marking it as the only known shocked zircon from Mars.

On Earth, zircon is very common and found in most igneous and metamorphic rocks. Australia has the world’s largest resources of zircon, which is used in electronics, engines, and spacecraft.

The new research was funded by the Australian Research Council, Curtin University, University of Adelaide and the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

1Comments