Provocateurs could start violence during March for Science against Donald Trump, former Obama science adviser warns

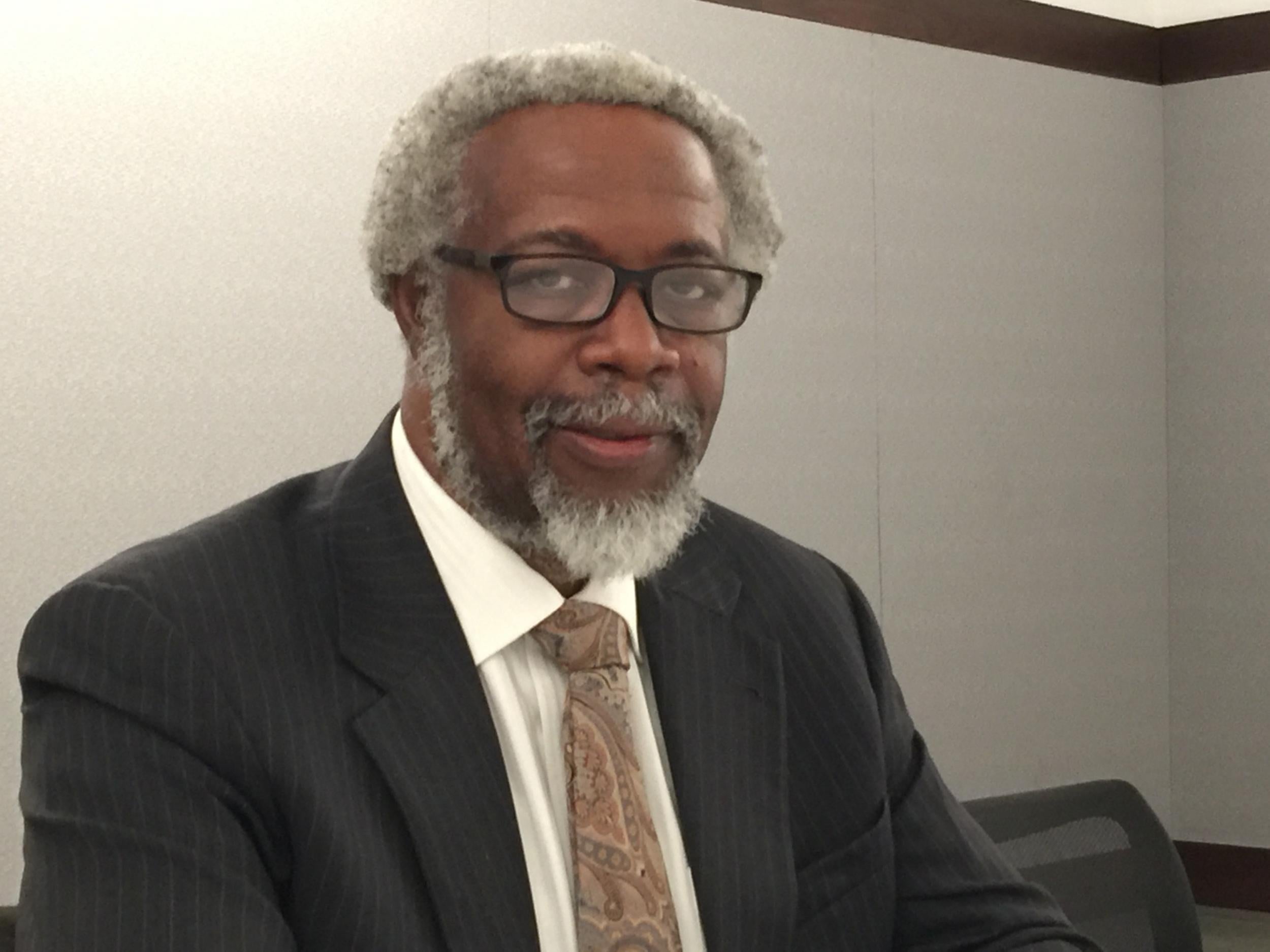

'To have sort of science represented as this political force I think is just extraordinarily dangerous,' says Professor James Gates

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The March for Science in response to the election of Donald Trump could be infiltrated by provocateurs and descend into violence, a physicist who advised Barack Obama has warned.

Professor James Gates, director of the Centre for String and Particle Theory at Maryland University and a member of the last administration’s US President’s Council of Advisers on Science and Technology, said he would not join the demonstration.

The march, due to be held in Washington DC and other cities around the world in April, echoes earlier Women’s Marches protesting against Mr Trump.

Scientists have been alarmed by the new President’s anti-scientific stance on climate change, the appointment of sceptics to key positions in Government, the deletion of information on federal websites and gag orders being issued to prevent researchers from speaking publicly about their work.

At the beginning of the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s annual meeting in Boston, the leaders of the body reported some scientists feared the US could become like Soviet Russia, where ideology outweighed hard evidence.

But Professor Gates told journalists ahead of his speech at the meeting that holding a march was not a good idea.

“I think scientists need to be very careful about putting the imprimatur of science on an activity like that,” he said.

Asked if he feared the march could widen the divide between scientists and the rest of the population by contributing to the idea that academics are elitist, Professor Gates said it might.

But he added: “To me the bigger danger is I don’t understand how the organisers of this march can guard against provocateurs, quite frankly.

“I don’t think they are ready for that. I don’t they are considering that kind of danger.

“And to have sort of science represented as this political force I think is just extraordinarily dangerous.

“You could actually have physical violence, but the point is I don’t want to see the march where it says ‘science against the President’. To me, that’s just terrible.”

The organisers of the march have insisted they want the event to be non-partisan.

“They are attempting to [make it apolitical], but I don’t see how they control that,” Professor Gates said.

“I just want scientists to behave like scientists. The point is let’s do this on the basis of some evidence.”

As scientists, he said, the organisers should have a “theory of action” that laid out what would happen after the march.

“What is your next step in the process? No one has explained this to me,” Professor Gates said.

“I find it curious for scientists to be behaving in this way."

He agreed that science was “facing some challenges in my homeland”, but this had been the case for long before Mr Trump’s election.

“This challenge has been on the horizon for a decade or more,” he said, dating the birth of anti-scientific sentiment to the US’s decision not to build its own, much more powerful version of the Large Hadron Collider at Cern, in Switzerland.

The LHC went on to discover the Higgs’ bosun, a particle that confirmed theories about how the universe was created, leading to Nobel Prizes for the scientists involved, including Professor Peter Higgs of Edinburgh University, who first came up with the idea.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments