Study finds how lizard tails are sturdy at regular times but detach easily when needed

Findings may lead to novel designs to solve adhesion challenges in robotics and prosthetics

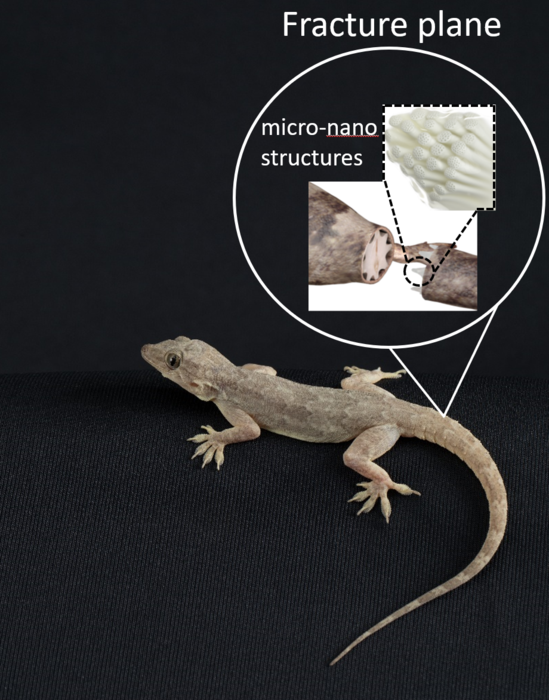

Tiny structures made up of mushroom-shaped micropillars topped with ultra-small pores allow lizards to quickly detach their tails when needed, a new study has found.

The research, published on Thursday in the journal Science, not only sheds light on how the tails are sturdy at regular times but detach easily when needed, but may also lead to novel technologies with new bio-inspired design ideas that solve adhesion and quick-release challenges.

Several lizard species can rapidly shed their tails to distract and escape from pursuing predators, a well-studied trait called autotomy. However, the tail also serves important balance functions when the lizards move and jump, and need them to remain firmly in place at most times.

While earlier studies have described the segmented anatomy of the lizard tail, the quick-release mechanism which enables autotomy isn’t fully understood, say scientists including Navajit Baban from New York University Abu Dhabi in UAE.

In the study, scientists developed a new model of lizard tail detachment and release based on microscopy images of the broken ends of lizard tails from two species of the Gekkonidae and one species of the Lacertidae lizard family.

They gently amputated tails from the lizards and analysed the broken sections under a microscope.

Microscopy images showed that each lizard tail muscle break-off point consists of highly dense mushroom-shaped micropillars with ultra-small nanopores dotting the top of each. These sections work like plugs into sockets, and the tail tends to break off these points – called fracture planes.

Scientists also tested the forces at work and the functioning of the tail microstructures by building a bio-inspired model using micropillars made of the polymeric material polydimethylsiloxane along with nanoporous tops.

They found that the the tail’s structure consisting of deep crevasses between micropillars and other smaller potholes on their surfaces could slow the spread of an initial fracture on the tail.

Their new model suggests that these microstructures in the lizard tail allow for enhanced adhesion under tension, but when faced with a slight twist, the fracture plane cracks, and the tail can separate.

This microstructure, researchers believe, plays a key role in balancing self-amputation when under threat and keeping the tails intact, achieving the “just right” Goldilocks zone in tail connection that is neither too weak nor too strong for the reptile’s chance of survival.

“Thus, autotomy proves to be a successful survival tool in the natural world, and its prevalence in both plants and animals gives confidence that it may be useful for scientific and engineering applications,” Animangsu Ghatak from the Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur, wrote in a related commentary article on the study.

“Particularly in robotics, stealth technology and prosthetics and for the safe operation of many critical installations, an optimised link similar to the one at present at the lizard tail can go a long way in protecting and expensive component or device from an unforeseen accident or mishap.” Dr Ghatak, who was not part of the study, added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks