Lab-grown vaginas prove long-term success for four women born without one

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists in the USA have completed the first successful implants of “lab-grown” vaginal organs, in four women with a rare condition who were born without a vagina.

The extraordinary procedures, carried out between 2005 and 2008, have proved a long-term success, with all four patients, who were aged between 13 and 18 at the time of the operation, able to become sexually active without any discomfort.

It is the first time that vaginas grown from the patient’s own cells have been implanted and the experts behind the procedure said it had was superior to existing reconstructive methods.

All four patients had been diagnosed with the rare Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. Women with MHRK are born without a vagina, cervix, or womb. It affects one in every 5,000 women.

Existing treatments for women living with MHRK include stretching the small amount of vaginal tissue present, and women are usually able to have comfortable sex but are unable to become pregnant.

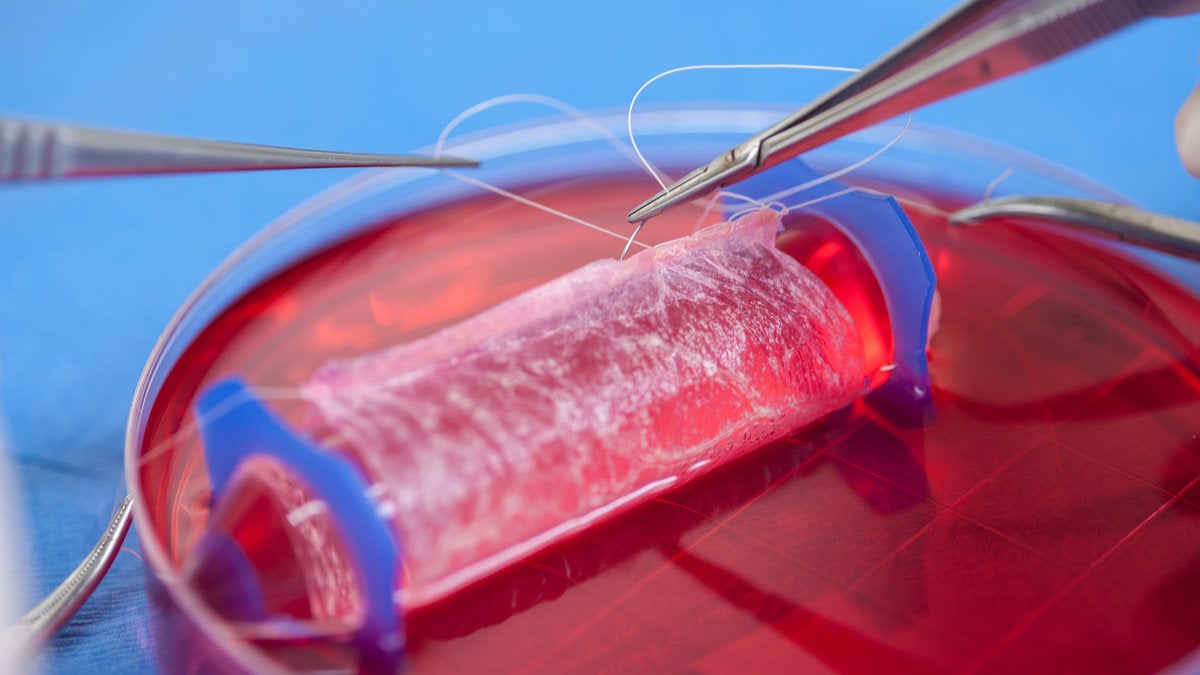

The new technique, which has been trialled by a team of scientists in the USA and Mexico, led by Professor Anthony Atala of the Wake School of Medicine, saw the four patients undergo a biopsy to remove tissue from the vulva, which was used to cells in the lab. The cells were then placed on a biodegradable, vagina-shaped “scaffold”, hand-sewn and tailor made for the patient, and left to grow.

Researchers then surgically implanted the scaffolds, which once implanted, lead to expansions of nerves and blood vessels, which form tissue. As the biodegradable material is absorbed into the body the cells form into a permanent organ.

As many as eight years later, patients reported normal sexual function, and no pain. Because women with MHRK do not have a developed womb, the patients were unable to become pregnant. However, women with the condition can produce eggs, which can be used for IVF treatment.

“This technique is a viable option for vaginal reconstruction and has several advantages over current reconstructive methods because only a small biopsy of tissue is required and using vaginal cells may reduce complications that arise from using non-vaginal tissue, such as infection,” said Professor Atala.

Engineering organs for transplant from patients own tissue is a growing field of science which some experts believe could one day replace the need for organ donors. However, the procedures carried out by Professor Atala and his team represent only the first successful attempts and widespread clinical use is a long way off.

In another first, scientists in Switzerland have used similar techniques to reconstruct the nostrils of five patients, using cells from their nasal septum. The technique could be used to treat people who have had parts of their nose removed to prevent non-melanoma skin cancer, which commonly occurs on the skin of the nose, the researchers said.

A year after the procedure, all five patients said they were happy with both their ability to breathe with the engineered nostrils, and with their appearance.

Both studies are published in The Lancet medical journal today.

Martin Birchall, professor of laryngology at University College London and one of the UK’s leading ear, nose and throat surgeons, said that the findings “start to edge tissue engineering towards the mainstream of organ and tissue replacement needs”.

“These authors have not only successfully treated several patients with a difficult clinical problem, but addressed some of the most important questions facing translation of tissue engineering technologies,” he said, adding it was time for the healthcare industry to take the new tissue engineering techniques seriously and speed their development.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments