Kraken: The real-life origins of the legendary sea monster

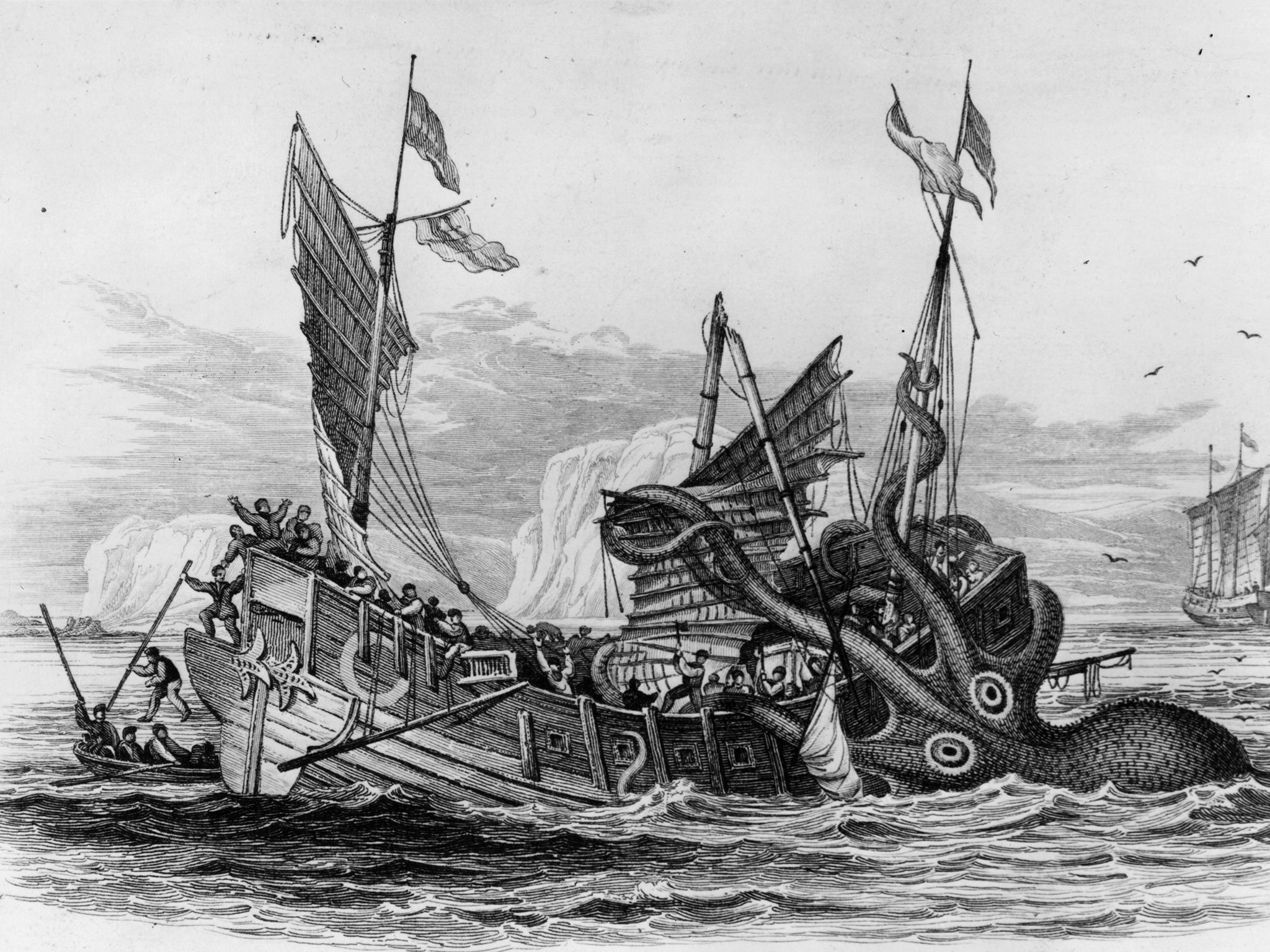

Legends say that the fearsome Kraken could devour a ship’s entire crew at once

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Kraken is perhaps the largest monster ever imagined by mankind. In Nordic folklore, it was said to haunt the seas from Norway through Iceland and all the way to Greenland.

The Kraken had a knack for harassing ships and many pseudoscientific reports (including official naval ones) said it would attack vessels with its strong arms. If this strategy failed, the beast would start swimming in circles around the ship, creating a fierce maelstrom to drag the vessel down.

Of course, to be worth its salt, a monster needs to have a taste for human flesh. Legends say that the Kraken could devour a ship’s entire crew at once.

But despite its fearsome reputation, the monster could also bring benefits: it swam accompanied by huge schools of fish that cascaded down its back when it emerged from the water. Brave fishermen could thus risk going near the beast to secure a bounteous catch.

The history of the Kraken goes back to an account written in 1180 by King Sverre of Norway. As with many legends, the Kraken started with something real, based on sightings of a real animal, the giant squid. For the ancient navigators, the sea was treacherous and dangerous, hiding a horde of monsters in its inconceivable depths. Any encounter with an unknown animal could gain a mythological edge from sailors' stories. After all, the tale grows in the telling.

Scientific legend

The strength of the myth became so strong that the Kraken could still be found in Europe’s first modern scientific surveys of the natural world in the 18th century. Not even Carl Linnaeus – father of modern biological classification – could avoid it and he included the Kraken among the cephalopod mollusks in the first edition of his groundbreaking Systema Naturae (1735).

But when, in 1853, a giant cephalopod was found stranded on a Danish beach, Norwegian naturalist Japetus Steenstrup recovered the animal’s beak and used it to scientifically describe the giant squid, Architeuthis dux. And so what had become legend officially entered the annals of science, returning our image of the Kraken to the animal that originated the myths.

After 150 years of research into the giant squid that inhabits all the world’s oceans, there is still much debate as to whether they represent a single species or as many as 20. The largest Architeuthis recorded reaches 18 metres in length, including the very long pair of tentacles, but the vast majority of specimens are much smaller. The giant squid’s eyes are the largest in the animal kingdom and are crucial in the dark depths it inhabits (up to 1,100 metres deep, perhaps reaching 2,000 metres).

Like some other squid species, Architeuthis has pockets in its muscles containing an ammonium solution that is less dense than sea water. This allows the animal to float underwater, meaning that it can keep itself steady without actively swimming. The presence of unpalatable ammonium in their muscles is also probably the reason why giant squid have not yet been fished to near extinction.

Hunter or prey?

For many years, scientists debated whether the giant squid was a swift and agile hunter like the powerful predator of legends or an ambush hunter. After decades of discussion, a welcome answer came in 2005 with the unprecedented film footage from Japanese researchers T. Kubodera and K. Mori. They filmed a live Architeuthis in its natural habitat, 900m deep in the North Pacific, showing that it is in fact a fast and powerful swimmer, using its tentacles to capture prey.

Despite its size and speed, Architeuthis has a predator: the sperm whale. The battles between these titans must be frequent, since it is common to find scars on whales’ skins left by the squids’ tentacles and arms, which have suckers lined with sharp chitinous tooth-like structures. But Architeuthis doesn’t have the muscles in its tentacles to use them to constrict prey and it can never overcome a sperm whale in a “duel”. Its only option is to flee, covering its escape with the usual cephalopod ink cloud.

Although we now know it is not just a legend, the giant squid remains perhaps the most elusive large animal in the world, which has greatly contributed to its aura of mystery. Many people today are still surprised in learning that it really exists. After all, even after so much scientific research, the Kraken is still alive in popular imagination thanks to films, books and computer games, even if it sometimes turns up in the wrong mythology, such as the 1981 (and 2010) ancient Greek epic Clash of the Titans. These representations have come to define it in the public mind: a beast lurking in sunken ships waiting for reckless divers.

Rodrigo Brincalepe Salvador, PhD student in Paleontology, University of Tübingen

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments