If the slump wasn't bad enough, stand by for the literary misery that's bound to follow

Scientists discover link between downturns and an increase in frequency of words of 'emotional malaise'

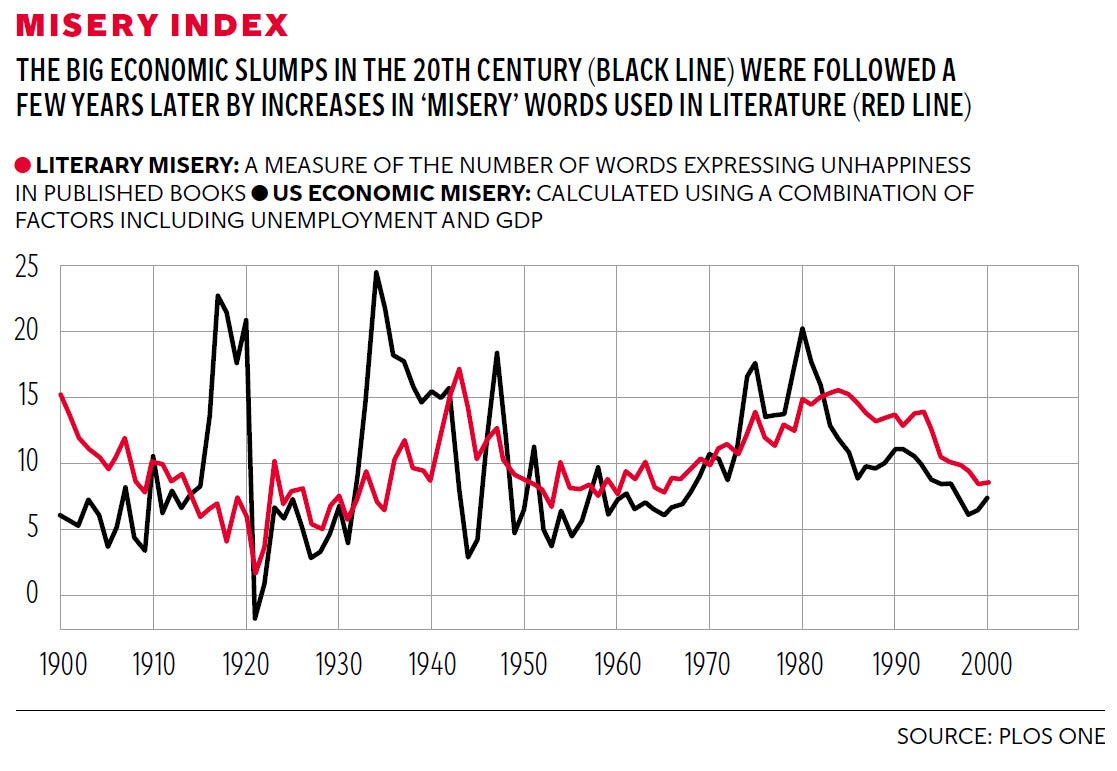

Be prepared for literary misery in the next few years because an economic slump like the one we've just experienced is almost always followed by a flood of miserable words in books published a decade or so later, a study has found.

Scientists have discovered a link between the deep financial downturns of the last century and an increase in the frequency of words associated with emotional malaise used in books published about 11 or 12 years later - and they think the former causes the latter.

The study analysed the word content in the digital library of books being amassed by Google and found that the popularity of words expressing unhappiness reflected the economic conditions that prevailed when many of the authors were children or adolescents.

The researchers believe that the association - which they found in both English and German literature - was not just a fluke of chance but a direct result of authors being influenced by what happened during the most formative stages of their development.

"Perhaps this decade effect reflects the gap between childhood, when strong memories are formed, and early adulthood, when authors may begin writing books," said Professor Alex Bentley of Bristol University, the lead author of the study published in the on-line journal PlosOne.

"Consider for example the dramatic increase of literary misery in the 1980s, which follows the stagflation of the 1970s. Children from this generation who became authors would have begun writing in the 1980s," Professor Bentley said.

The study analysed literature published during the 20th Century, and the various economic ups and downs of the period - it did not include the current economic recession which began in 2008. However, Professor Bentley is confident that we can expect more literary gloom in the very near future.

"Writers are often influences by the economic conditions of the last decade. In 10 years' time I think we'll see an increase in the literary misery index," he said.

The study did not look at individual books and so could not analyse the novels dedicated to economic depression, such as the John Steinbeck canon, but merely analysed the frequency with which authors used key words associated with unhappiness. Because it looked at the overall digital database of words, it also took no account of how popular each book was in terms of sales.

"The changes in the words being used were drive by the authors, not by the demand from readers," Professor Bentley said.

However, the clear pattern over the 100-year period was that an economic slump with high unemployment is almost invariably followed a predictable period later by novels that are rich in words expressing emotional unhappiness, the study found.

"Economic misery coincides with World War I in 1918, the aftermath of the Great Depression in 1935 and the energy crisis of 1975. But in each case, the literary response lags by about a decade," said Alberto Acerbi of Bristol University, one of the co-authors of the study.

To test the idea, the researchers also looked at books published in German to see if they matched the ups and downs of the German economy over the same period. The findings were very similar despite the differences in the economy of Germany and the United States, the researchers said.

"The results suggest that millions of books published every year average the authors' shared economic experience over the past decade," they said.

Read ’em and weep: Depressing titles

Of Mice and Men, by John Steinbeck

The novella published in 1937 that came to symbolise the Great Depression tells the story of two migrant field workers in California. George looks out for his friend Lennie, a man of great strength but limited mental abilities. When Lennie accidently kills a woman, George decides to shoot him in the back of the head, so that his inevitable death will be painless and happy.

The Bell Jar, by Sylvia Plath

Published in 1963, Plath’s only novel is about Esther Green’s battle with mental illness while at college. As Green’s depression deepens, she finds herself increasingly cut off from society. The lead character’s descent into mental illness parallels Plath’s own experiences with what may have been clinical depression, and the author committed suicide a month after the book’s first UK publication.

The Road, by Cormac McCarthy

The 2006 novel is a post-apocalyptic tale documenting the journey of a dying father and his young son over several months, after a disaster destroys most of civilisation. The pair witness a new-born infant being roasted on a spit and captives being harvested as food. The son holds wake over his dead father’s body for three days.

Chloe Hamilton

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks