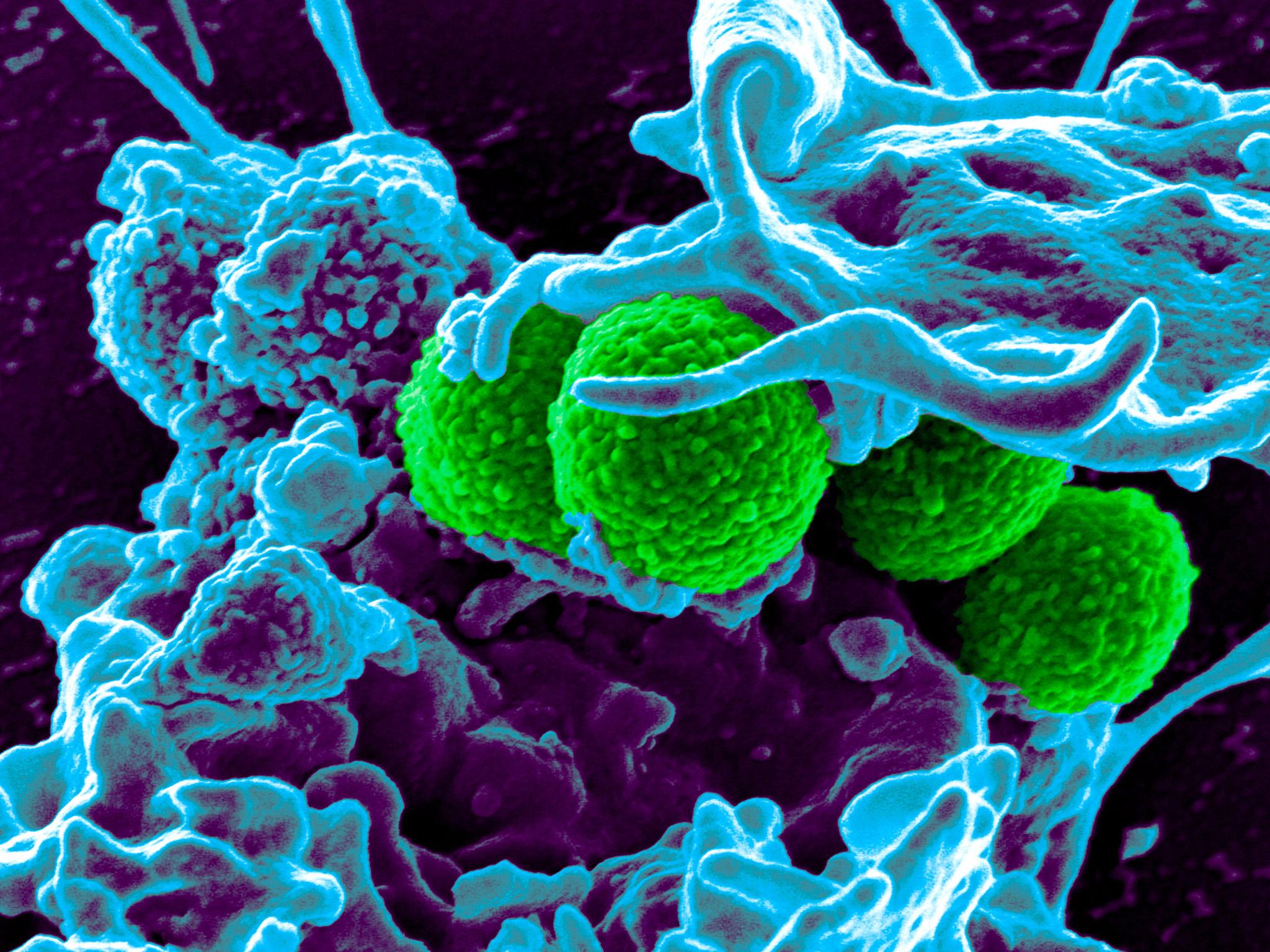

Human-virus hybrid created to kill off antibiotic-resistant MRSA superbug

Tests are underway to establish if equipping a human immune cell with a 'targeting device' from a virus is safe

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Human cells have been mixed with bacteria and viruses to create a hybrid immune cell that can kill off deadly resistant bacteria, scientists have said.

Some viruses are designed to infect bacteria and target their prey in a different way to the human immune system.

The researchers were able to take the virus’s targeting mechanism and graft it onto a human immune antibody. They then did the same with bacteria, which attack other bacteria, and a human antibody.

In experiments in the lab the hybrids, dubbed “lysibodies”, attached themselves to Staphylococcus bacteria – which can become the resistant superbug MRSA. This then signalled the immune system to attack and destroy the bacteria.

Tests of the technique on mice infected with MRSA found their survival rate was significantly improved, the researchers said.

Human testing has now begun to establish whether the lysibodies are safe and how effective they are.

One of the researchers, Professor Vincent Fischetti, of The Rockefeller University in the US, said: “Bacteria-infecting viruses have molecules that recognize and tightly bind to these common components of the bacterial cell’s surface that the human immune system largely misses.

“We have co-opted these molecules, and we've put them to work helping the human immune system fight off microbial pathogens.”

Some viruses have “molecular snippers”, called lysins, that target carbohydrates on the bacteria’s cell walls.

Human antibodies are designed to target proteins and have a bit of a blind spot for carbohydrates.

By creating a hybrid with a human immune cell, this should give the body a whole new way to identify disease cells.

And Professor Fischetti added: “Based on our results, it may be possible to use not just lysins, but any molecule with a high affinity toward a target on any pathogen – be it virus, parasite, or fungus – to create hybrid antibodies.

“This approach could make it possible to develop a new class of immune boosting therapies for infectious diseases.”

The human immune antibodies used in the hybrids do not attack the disease, but instead flag up targets for immune system killer cells.

Dr Assaf Raz, also of Rockefeller, who led the experiments, said: “Both antibodies and lysins have two discrete components.

“They both have a part that binds their respective target, but whereas the second component of lysins cuts the bacterial cell wall, in antibodies it coordinates an immune response.

“This made it possible for us to mix and match, combining the viral piece responsible for latching onto a carbohydrate with the part of the antibody that tells immune cells how to respond.”

It usually takes years for a new drug to get from tests of safety and effectiveness to the point where it could be used as a medicine.

Doubtless there will be concerns about potential for unintended consequences from mixing human with viral or bacterial material.

However the research has attracted interest from the Tri-Institutional Therapeutics Discovery Institute in the US, a partnership established to expedite early-stage drug discovery.

It is already manufacturing lysibodies and has plans to begin testing their safety.

The research was described in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments