How the demise of the dinosaurs led to super-sized mammals

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

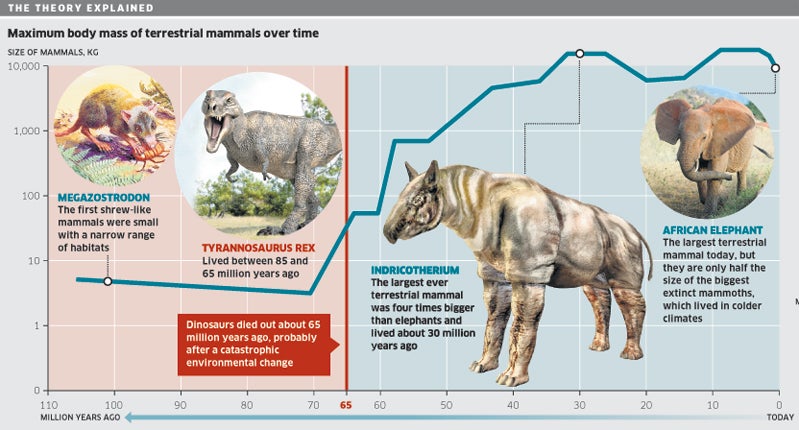

Your support makes all the difference.The demise of the dinosaurs created the ecological opportunity for the diminutive prehistoric mammals of the time to become the largest creatures on Earth today, scientists have demonstrated conclusively for the first time.

A worldwide study of fossilised mammals has demonstrated beyond any doubt that it was the extinction of the dinosaur some 65 million years ago that was the key trigger leading to the explosive growth of the warm-blooded mammals.

Although it was long suspected that this was the reason for the transition from dinosaur dominance to mammalian supremacy, a thorough investigation of fossil mammals dating back 140 million years has confirmed that we would not have elephants today had it not been for the death of Argentinosaurus, one of the biggest-ever dinosaur, and others like it.

The study found that for the first 40 million years or so of their existence, the mammals were mostly small, shrew-like creatures that lived in a narrow range of habitats.

However, after the dinosaur disappeared, the mammals evolved relatively rapidly into much larger creatures capable of exploiting a wide variety of ecological niches, from leaf-eating giant sloths to tundra-munching mammoths.

"Basically, the dinosaur disappear and all of a sudden there is nobody else eating the vegetation. That's an open food source and mammals start going for it, and it's more efficient to be aherbivore when you're big," said Jessica Theodor of the University of Calgary in Canada. "You lose dinosaur 65 million years ago, and within 25 million years the system is reset to a new maximum for the animals that are there in terms of body size. That's actually a pretty short time frame, geologically speaking. That's really rapid evolution," Professor Theodor said.

The study in the journal Science found that many different types of mammals grew into gigantic forms on different continents. The biggest was a hornless rhinoceros-like herbivore that lived in Eurasia 34 million years ago called Indricotherium transouralicum, which weighed 17 tons and stood 18ft high at the shoulder – four times the size of a modern elephant.

Being big is an advantage in a habitat with a large landmass of lots of vegetation, although it can make species vulnerable to sudden extinction if the environment changes rapidly.

With the dinosaur gone, and no other large animals already on Earth to take their place, the scene was set for the mammals to evolve into bigger and bigger forms that could better exploit the natural resources available to them.

"Nobody has ever demonstrated that this pattern is really there. People have talked about it, but nobody has ever gone back and done the math. We went through every time period and said 'OK, for this group of mammals that's the biggest one?' And then we estimated its body mass," Professor Theodor said. John Gittleman of the University of Georgia, who took part in the study, said that the fossil record for mammals was better than for many other animals, which was a key factor that helped to nail down the main conclusion.

"Once dinosaur went extinct, mammals evolved to be much larger as they diversified to fill the ecological niches that became available.

"This phenomenon was well documented in North America. We wanted to know if the same thing happened all over the world," Dr Gittleman said. "Having so many different lineages independently evolve to such similar maximum sizes suggests that there were similar ecological roles to be filled by giant mammals across the globe," he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments