How did five million barrels of oil simply disappear?

Steve Connor explains the science behind the natural – and man-made – processes at work in the Gulf of Mexico

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.British scientists with extensive experience of oil spills have supported their American counterparts who believe that most of the oil from the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico no longer poses a threat to wildlife.

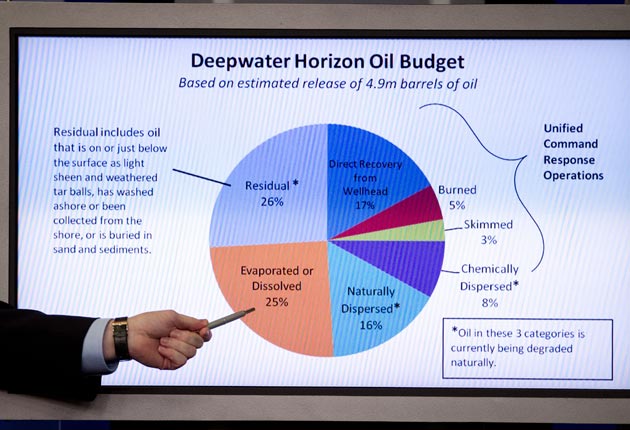

Only about one-quarter of the estimated 4.9 million barrels of oil from the spill in the Gulf remains as a residue in the environment, according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The other three-quarters no longer poses a significant threat to the environment, having mostly either evaporated or been dispersed, skimmed or burned off from from the sea surface, the NOAA scientists said.

Although the amount of oil still remaining in the environment, nearly 1.3 million barrels, is about five times the amount spilled in the Exxon Valdez disaster in Alaska in 1989, scientists believe that it is unlikely to cause as much damage as this notorious spill. The oil from the Gulf of Mexico is lighter than the usual heavy crude oil, and it will be easier to degrade naturally because there is a greater volume of water so it will dilute faster, and the warmer temperatures of the Gulf help bacterial degradation.

"This is good news. We've been saying all along that this wasn't the catastrophe that the politicians and the media would have us believe – but of course there is no such thing as a good oil spill," said Simon Boxall, an oceanographer from the National Oceanography Centre at Southampton University.

"It has caused a lot of damage to the coastline and it is a tragedy for everyone affected, but it is not the catastrophe that everyone was talking about," said Dr Boxall, who was involved in the assessment of the environmental impact of the MV Braer tanker disaster off the Shetlands in 1993. "It is not the world's worst environmental disaster, and not even the worst oil spill."

The NOAA investigation, led by the administration's head, Jane Lubchenco, found that the efforts to contain the oil spill in the Gulf, namely the direct recovery of oil as it spewed from the wellhead, the burning and skimming from the surface, and dispersal with chemical sprays, accounted for about a third of the oil that leaked from the well following the massive explosion and fire on 20 April that killed 11 oil workers.

Another 16 per cent of the 4.9 million barrels was naturally dispersed in the water column, mostly as a result of the oil forming small droplets no thicker than a human hair, as it sprayed from the wellhead under high pressure. Another 25 per cent of the oil either evaporated or dissolved into the seawater, the NOAA report says.

The remaining residue of 26 per cent exists in a combination of categories which are difficult to measure or estimate. "It includes oil still on or just below the surface in the form of light sheen or tar balls, oil that has washed ashore or been collected from the shore, and some that is buried in sand and sediments and may resurface through time. This oil has also begun to degrade through natural processes," the NOAA report says, while oil from the spill is being "degraded naturally by oil-eating microbes in the ocean and the rate at which this is taking place is higher than expected because of the warm sea temperatures".

Dr Lubchenko said that NOAA does not believe that it has missed any huge amounts of oil still lurking below the surface of the sea but she warned that there may still be some longer-term effects on the environment as a result of the leak, which is now the biggest offshore oil spill. "Dilute and out of sight does not necessarily mean benign and we remain concerned about the long-time impacts both on the marshes and the wildlife but also beneath the surface," Dr Lubchenko said.

Geoffrey Maitland, professor of energy engineering at Imperial College London, said that the NOAA estimates are very much in line with his own.

"Although the estimates confirm that this is indeed the biggest offshore oil spill [it] has not turned out to be anywhere near as bad as was feared in the first month or so of this crisis," Professor Maitland said.

The report described how US scientists used an "oil budget calculator" to estimate how much oil had been released each day leading up to the point on 15 July when the wellhead on the seabed was sealed by a cap.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments