Holograms projected onto brain could help replace lost senses

Scientists say early stage technology could one day 'allow the blind to see or the paralysed to feel touch'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A device that could one day “allow the blind to see or the paralysed to feel touch” by projecting holograms onto brain cells is being developed by scientists.

By using light as a tool to alter brain function, it might be possible to mimic real sensations and perceptions, they have suggested.

Named the “holographic brain modulator”, the device is still in its very early stages, but in a new paper published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, the researchers outlined some promising early results.

“This is one of the first steps in a long road to develop a technology that could be a virtual brain implant with additional senses or enhanced senses,” said Dr Alan Mardinly, a neuroscientist at the University of California, Berkeley, who participated in the work.

The researchers hope that from their initial experiments modifying the brain cells of mice, the technology will one day have the capacity to mimic senses such as sight or touch in people who have lost them.

“The ability to talk to the brain has the incredible potential to help compensate for neurological damage caused by degenerative diseases or injury,” said Professor Ehud Isacoff, another Berkeley scientist who was not involved in the project.

“By encoding perceptions into the human cortex, you could allow the blind to see or the paralysed to feel touch.”

The device makes use of a technique known as optogenetics, which involves the use of light to control living cells.

The basis of this technique is the insertion of light-sensitive channels into brain cells that open when they are struck by a beam of light. The opening of these channels stimulates the corresponding brain cell.

After inserting specially developed channels into the brains of mice, they were able to control the cells into which they had been added.

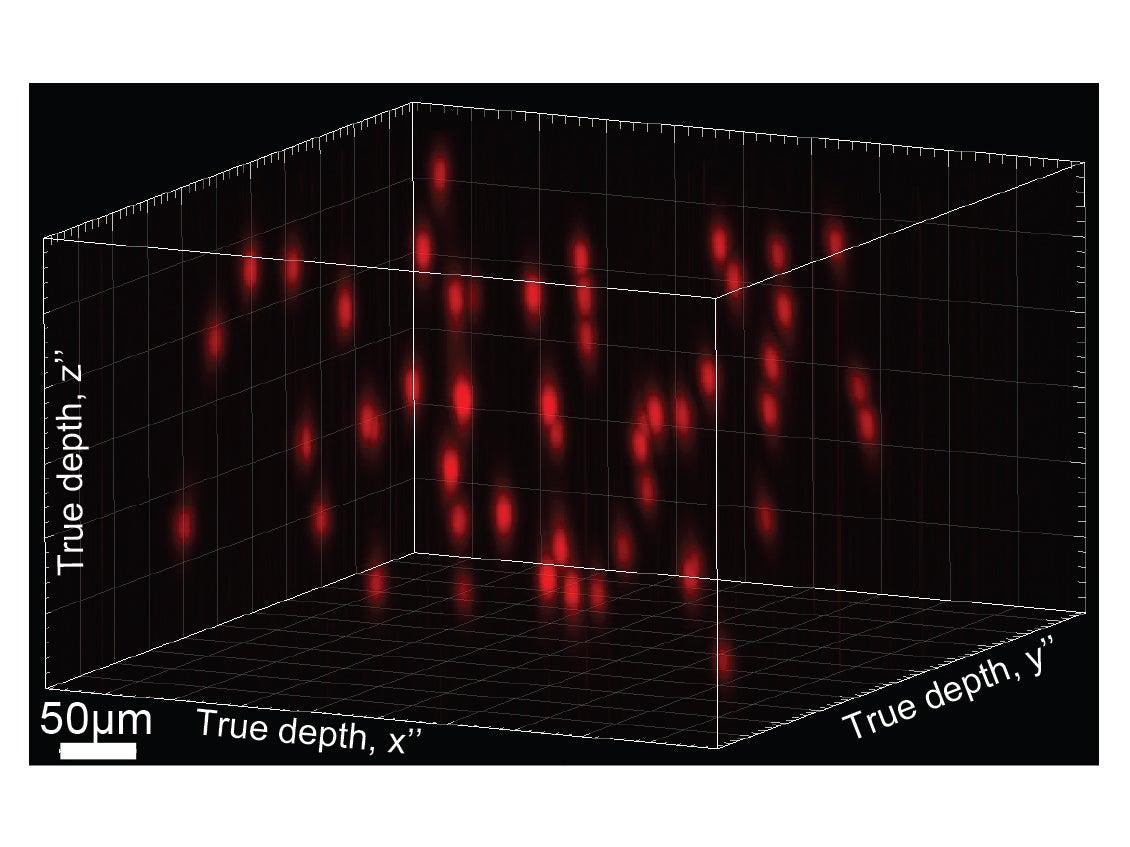

The scientists projected their hologram onto the top layer of the brain, activating dozens of neurons many hundreds of times a second in an effort to simulate real activity patterns in the brain.

By doing this, they hope to essentially fool the brain into thinking it has perceived something.

“This has great potential for neural prostheses, since it has the precision needed for the brain to interpret the pattern of activation,” said Dr Mardinly.

“If you can read and write the language of the brain, you can speak to it in its own language and it can interpret the message much better.”

The team’s experiments with mice have shown that this technology can cause changes in brain activity similar to those seen when the creatures are exposed to an actual sensory stimulus.

They are now training the mice to behave in certain ways so that they can gauge the extent to which their behaviours are altered by the holographic application.

The scientists also intend to imitate real patterns of brain activity so that they can ultimately reproduce sensations and perceptions that they can “play back” via the holographic system they have developed.

Although they have emphasise that the technology still has some way to go before it yields any life-changing benefits for humans, the technology is a significant advance on previous efforts to manipulate brain cells.

“The major advance is the ability to control neurons precisely in space and time,” said Dr Nicolas Pegard, an optics researcher at Berkeley and one of the study’s first authors. “In other words, to shoot the very specific sets of neurons you want to activate and do it at the characteristic scale and the speed at which they normally work.”

Dr Mardinly added: “This is the culmination of technologies that researchers have been working on for a while, but have been impossible to put together. We solved numerous technical problems at the same time to bring it all together and finally realise the potential of this technology.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments